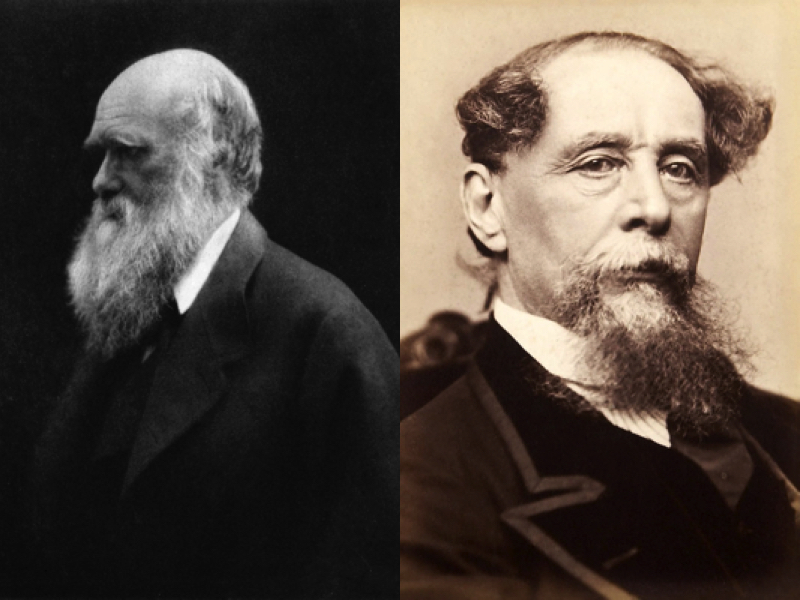

We all operate at different levels of ambition: some just want to get by and enjoy themselves, while others strive to make achievements with as long-lasting an impact on humanity as possible. If we think of candidates for the latter category, Charles Darwin may well come to mind, at least in the sense that the work he did as a naturalist, and more so the theory of evolution that came out of it, has ensured that we remember his name well over a century after his death and will surely continue to do so centuries hence. But research into Darwin’s working life suggests something less than workaholism — and indeed, that he put in a fraction of the number of hours we associate with serious ambition.

“After his morning walk and breakfast, Darwin was in his study by 8 and worked a steady hour and a half,” writes Nautilus’ Alex Soojung-kim Pang. “At 9:30 he would read the morning mail and write letters. At 10:30, Darwin returned to more serious work, sometimes moving to his aviary, greenhouse, or one of several other buildings where he conducted his experiments. By noon, he would declare, ‘I’ve done a good day’s work,’ and set out on a long walk.” After this walk he would answer letters, take a nap, take another walk, go back to his study, and then have dinner with the family. Darwin typically got to bed, according to a daily schedule drawn from his son Francis’ reminiscences of his father, by 10:30.

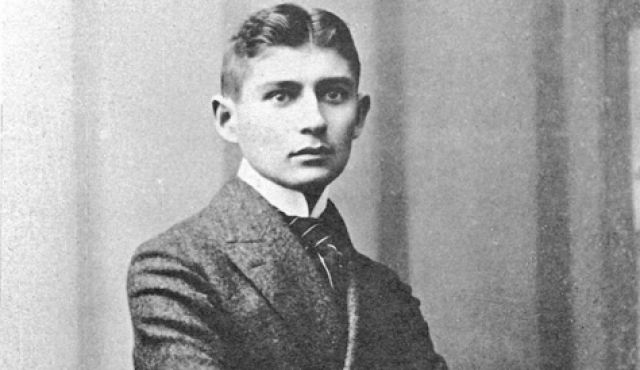

“On this schedule he wrote 19 books, including technical volumes on climbing plants, barnacles, and other subjects,” writes Pang, and of course not failing to mention “The Origin of Species, probably the single most famous book in the history of science, and a book that still affects the way we think about nature and ourselves.” Another textually prolific Victorian Englishman named Charles, adhering to a similarly non-life-consuming work routine, managed to produce — in addition to tireless letter-writing and campaigning for social reform — hundreds of short stories and articles, five novellas, and fifteen novels including Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, and Great Expectations.

“After an early life burning the midnight oil,” writes Pang, Charles Dickens “settled into a schedule as ‘methodical or orderly’ as a ‘city clerk,’ his son Charley said. Dickens shut himself in his study from 9 until 2, with a break for lunch. Most of his novels were serialized in magazines, and Dickens was rarely more than a chapter or two ahead of the illustrators and printer. Nonetheless, after five hours, Dickens was done for the day.” Pang finds that may other successful writers have kept similarly restrained work schedules, from Anthony Trollope to Alice Munro, Somerset Maugham to Gabriel García Márquez, Saul Bellow to Stephen King. He notes similar habits in science and mathematics as well, including Henri Poincaré and G.H. Hardy.

Research by Pang and others into work habits and productivity have recently drawn a great deal of attention, pointing as it does to the question of whether we might all consider working less in order to work better. “Even if you enjoy your job and work long hours voluntarily, you’re simply more likely to make mistakes when you’re tired,” writes the Harvard Business Review’s Sarah Green Carmichael. What’s more, “work too hard and you also lose sight of the bigger picture. Research has suggested that as we burn out, we have a greater tendency to get lost in the weeds.” This discovery actually dates back to Darwin and Dickens’ 19th century: “When organized labor first compelled factory owners to limit workdays to 10 (and then eight) hours, management was surprised to discover that output actually increased – and that expensive mistakes and accidents decreased.”

This goes just as much for academics, whose workweeks, “as long as they are, are not nearly as lengthy as those on Wall Street (yet),” writes Times Higher Education’s David Matthews in a piece on the research of University of Pennsylvania professor (and ex-Goldman Sachs banker) Alexandra Michel. “Four hours a day is probably the limit for those looking to do genuinely original research, she says. In her experience, the only people who have avoided burnout and achieved some sort of balance in their lives are those sticking to this kind of schedule.” Michel finds that “because academics do not have their hours strictly defined and regulated (as manual workers do), ‘other controls take over. These controls are peer pressure.’ ” So at least we know the first step on the journey toward viable work habits: regarding the likes of Darwin and Dickens as your peers.

via Nautilus

Related Content:

The Daily Habits of Highly Productive Philosophers: Nietzsche, Marx & Immanuel Kant

The Daily Habits of Famous Writers: Franz Kafka, Haruki Murakami, Stephen King & More

John Updike’s Advice to Young Writers: ‘Reserve an Hour a Day’

Thomas Edison’s Hugely Ambitious “To-Do” List from 1888

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To Do List (Circa 1490) Is Much Cooler Than Yours

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.