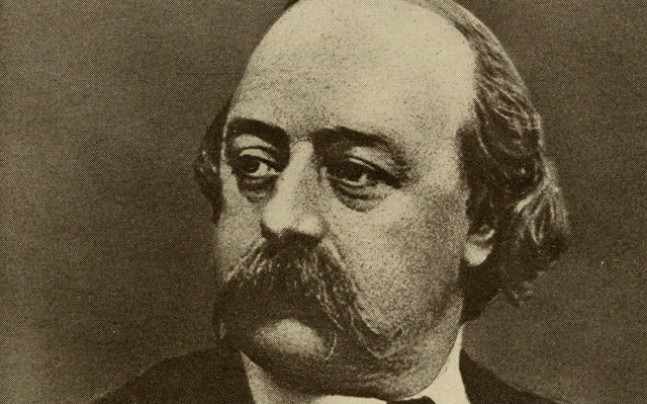

We are what we do — or in other words, we are what we choose to spend our time doing. By this logic, a “musician” who spends one quarter of his time with his instruments and three quarters with Excel, though he counts as no less a human being for it, should by rights call himself a maker of spreadsheets rather than a maker of music. This view may sound stark, but it has its adherents, some of them successful and respected artists. We can rest assured that no less a creator than Gustave Flaubert, for instance, would surely have accepted it, if we take seriously the words of a letter he wrote to his mother in February of 1850.

Though he’d completed several books at the time, the then 28-year-old Flaubert had yet to make it as a man of letters. He did, however, do a fair bit of traveling at that time in his life, composing this particular piece of correspondence during a sojourn in the Middle East. It seems that even halfway across the world, he couldn’t escape his mother’s entreaties to find proper employment, if only “un petite place” that would grant him slightly more social respectability and financial stability. Finally fed up, he clarified his position on the matter of day jobs once and for all:

Now I come to something that you seem to enjoy reverting to and that I utterly fail to understand. You are never at a loss of things to torment yourself about. What is the sense of this: that I must have a job — “a small job,” you say. First of all, what job? I defy you to find me one, to specify in what field, or what it would be like. Frankly, and without deluding yourself, is there a single one that I am capable of filling? You add: “One that wouldn’t take up much of your time and wouldn’t prevent you from doing other things.” There’s the delusion! That’s what Bouilhet told himself when he took up medicine, what I told myself when I began law, which nearly brought about my death from suppressed rage. When one does something, one must do it wholly and well. Those bastard existences where you sell suet all day and write poetry at night are made for mediocre minds — like those horses equally good for saddle and carriage — the worst kind, that can neither jump a ditch nor pull a plow.

In short, it seems to me that one takes a job for money, for honors, or as an escape from idleness. Now you’ll grant me, darling, (1) that I keep busy enough not to have to go out looking for something to do; and (2) if it’s a question of honors, my vanity is such that I’m incapable of feeling myself honored by anything: a position, however high it might be (and that isn’t the kind you speak of) will never give me the satisfaction that I derive from my self-respect when I have accomplished something well in my own way; and finally, if it’s for money, any jobs or job that I could have would bring in too little to make much difference to my income. Weigh all these considerations: don’t knock your head against a hollow idea. Is there any position in which I’d be closer to you, more yours? And isn’t not to be bored one of the principal goals of life?

The letter may well have convinced her: according to a footnote included in The Letters of Gustave Flaubert: 1830–1857, “there seem to have been no further suggestions” that he secure a steady paycheck. Could Flaubert’s mother have had an inkling that her son would become, well, Flaubert? At that point he hadn’t even begun writing Madame Bovary, a project that would begin upon his return to France. Its inspiration came in part from the early version of The Temptation of Saint Anthony he’d completed before embarking on his travels, which his friends Maxime Du Camp and Louis Bouilhet (the reluctant medical student mentioned in the letter) suggested he toss in the fire, telling him to write about the stuff of everyday life instead.

Not all of us, of course, can work the same way Flaubert did, with his days spent in revision of each page and his obsessive lifelong hunt for le mot juste: not for nothing do we call him “the martyr of style.” But whatever we create and however we create it, we ignore the words Flaubert wrote to his mother at our peril. The earning of money has its place, but the idea that any old day job can be easily held down without damage to our real life’s work shades all too easily into self-delusion. We must remember that “when one does something, one must do it wholly and well,” a sentiment made infinitely more powerful by the fact that Flaubert didn’t just articulate it, he lived it — and now occupies one of the highest places in the pantheon of the novel as a result.

h/t Tom H.

Related Content:

Read 4,500 Unpublished Pages of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

William Faulkner Resigns From His Post Office Job With a Spectacular Letter (1924)

Brian Eno’s Advice for Those Who Want to Do Their Best Creative Work: Don’t Get a Job

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.