As an artistic child growing up on a farm in the 1860s and early 1870s, Anna Mary Robertson (1860–1961) used ground ochre, grass, and berry juice in place of traditional art supplies. She was so little, she referred to her efforts as “lambscapes.” Her father, for whom painting was also a hobby, kept her and her brothers supplied with paper:

He liked to see us draw pictures, it was a penny a sheet and lasted longer than candy.

She left home and school at 12, serving as a full-time, live-in housekeeper for the next 15 years. She so admired the Currier & Ives prints hanging in one of the homes where she worked that her employers set her up with wax crayons and chalk, but her duties left little time for leisure activities.

Free time was in even shorter supply after she married and gave birth to ten children — five of whom survived past infancy. Her creative impulse was confined to decorating household items, quilting, and embroidering gifts for family and friends.

At the age of 77 (circa 1937), widowed, retired, and suffering from arthritis that kept her from her accustomed household tasks, she again turned to painting.

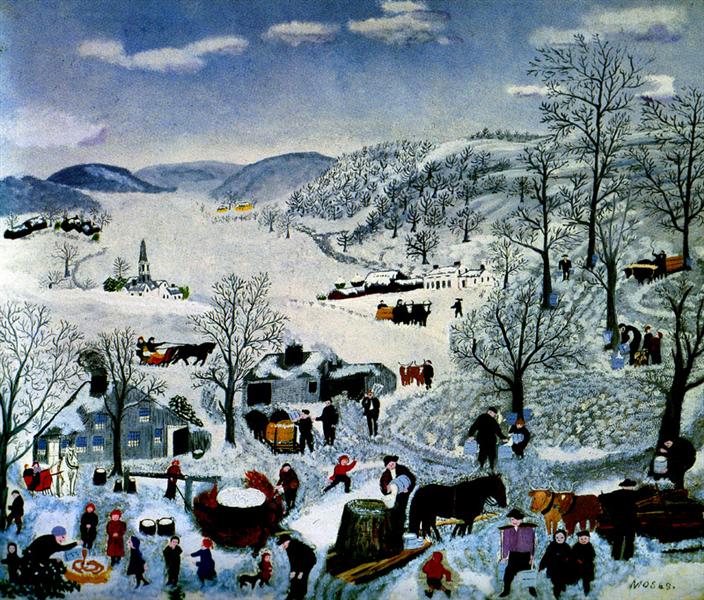

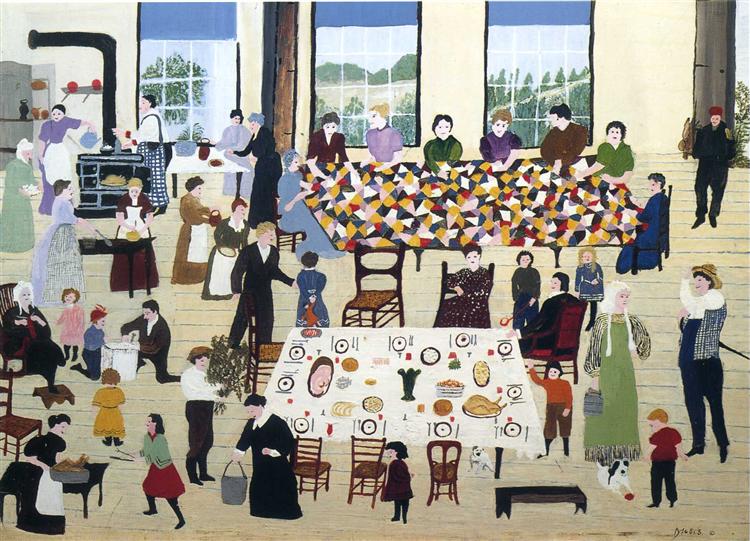

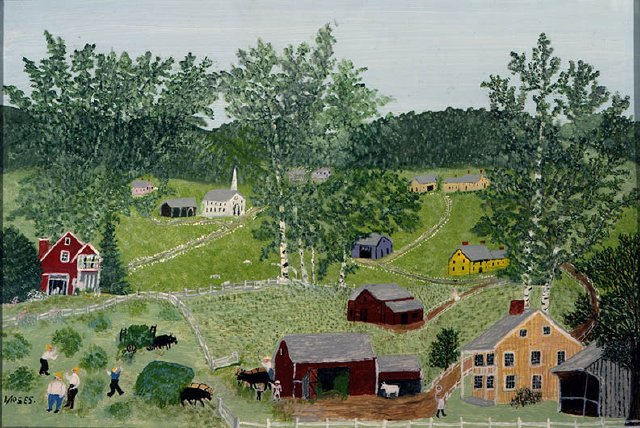

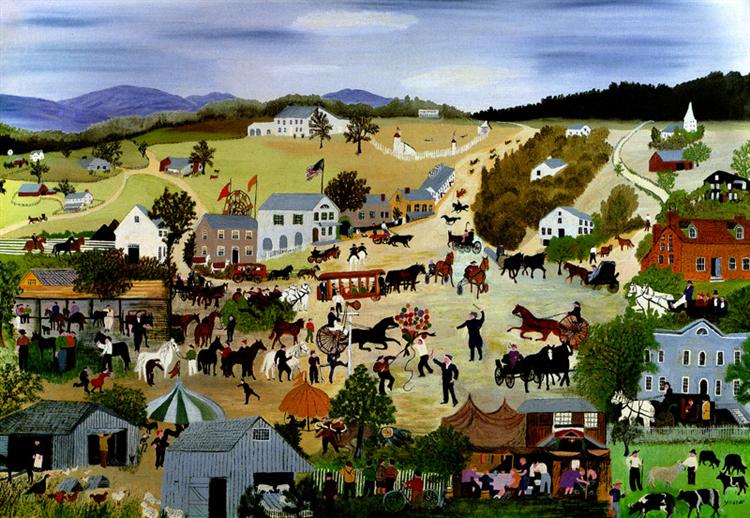

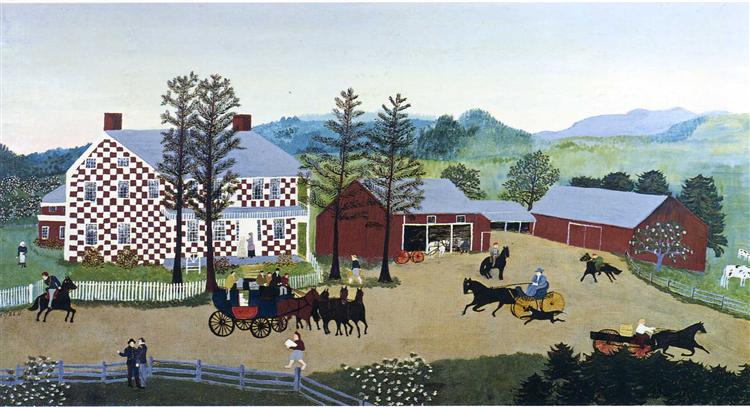

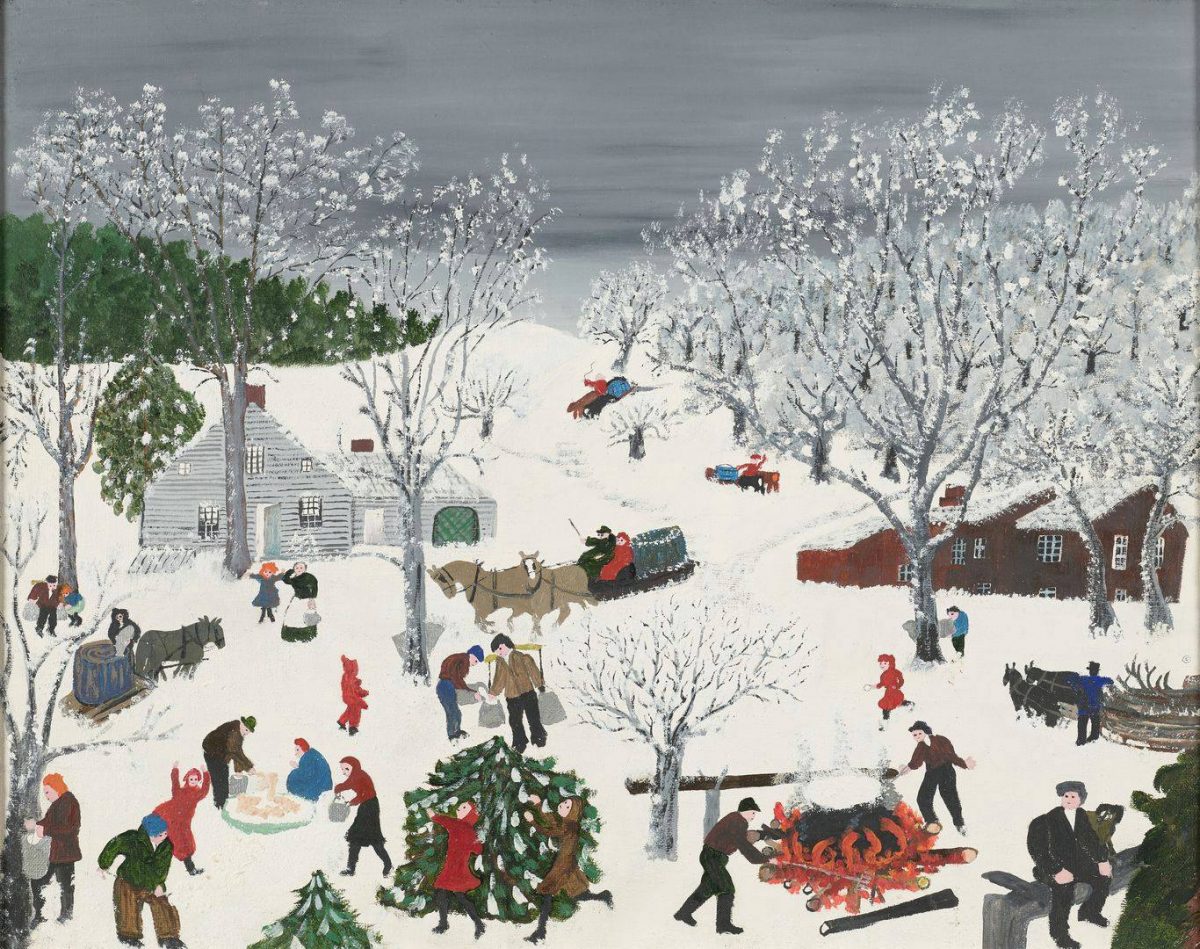

Setting up in her bedroom, she worked in oils on masonite prepped with three coats of white paint, drawing on such youthful memories as quilting bees, haying, and the annual maple sugar harvest for subject matter, again and again.

Thomas’ Pharmacy in Hoosick Falls, New York exhibited some of her output, alongside other local women’s handicrafts. It failed to attract much attention, until art collector Louis J. Caldor wandered in during a brief sojourn from Manhattan and acquired them all for an average price tag of $4.

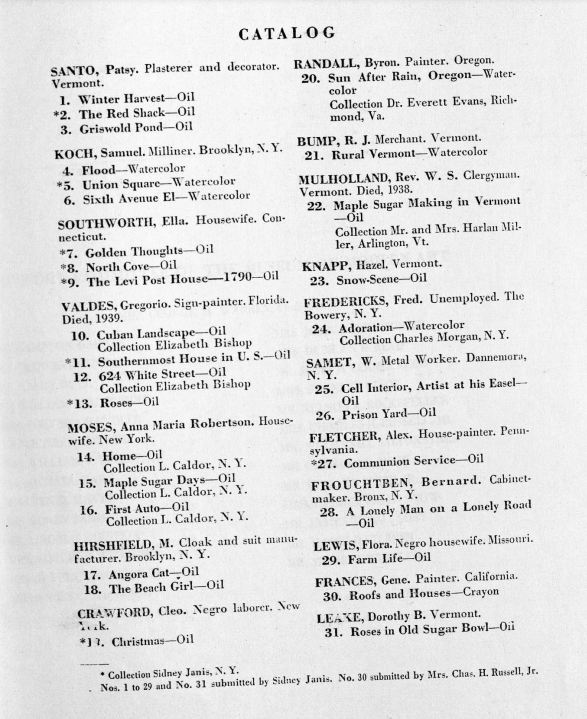

The next year (1939), Mrs. Moses, as she was then known, was one of several “housewives” whose work was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibit “Contemporary Unknown American Painters”. The emphasis was definitely on the untaught outsider. In addition to occupation, the catalogue listed the non-Caucasian artists’ race…

In short order, Anna Mary Robertson Moses had a solo exhibition in the same gallery that would give Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele their first American one-person shows, Otto Kallir’s Galerie St. Etienne.

In reviewing the 1940 show, the New York Herald Tribune’s critic cited the folksy nickname (“Grandma Moses”) favored by some of the artist’s neighbors. Her wholesome rural bonafides created an unexpected sensation. The public flocked to see a table set with her homemade cakes, rolls, bread and prize-winning preserves as part of a Thanksgiving-themed meet-and-greet with the artist at Gimbels Department Store the following month.

As critic and independent curator Judith Stein observes in her essay “The White Haired Girl: A Feminist Reading”:

In general, the New York press distanced the artist from her creative identity. They commandeered her from the art world, fashioning a rich public image that brimmed with human interest…Although the artist’s family and friends addressed her as “Mother Moses” and “Grandma Moses” interchangeably, the press preferred the more familiar and endearing form of address. And “Grandma” she became, in nearly all subsequent published references. Only a few publications by-passed the new locution: a New York Times Magazine feature of April 6, 1941; a Harper’s Bazaar article; and the landmark They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century, by the respected dealer and curator Sidney Janis, referred to the artist as “Mother Moses,” a title that conveyed more dignity than the colloquial diminutive “Grandma.”

But “Grandma Moses” had taken hold. The avalanche of press coverage that followed had little to do with the probity of art commentary. Journalists found that the artist’s life made better copy than her art. For example, in a discussion of her debut, an Art Digest reporter gave a charming, if simplified, account of the genesis of Moses’ turn to painting, recounting her desire to give the postman “a nice little Christmas gift.” Not only would the dear fellow appreciate a painting, concluded Grandma, but “it was easier to make than to bake a cake over a hot stove.” After quoting from Genauer and other favorable reviews in the New York papers, the report concluded with a folksy supposition: “To all of which Grandma Moses perhaps shakes a bewildered head and repeats, ‘Land’s Sakes’.” Flippantly deeming the artist’s achievements a marker of social change, he noted: “When Grandma takes it up then we can be sure that art, like the bobbed head, is here to stay.”

Urban sophisticates were besotted with the plainspoken, octogenarian farm widow who was scandalized by the “extortion prices” they paid for her work in the Galerie St. Etienne. As Tom Arthur writes in a blog devoted to New York State historical markers:

New Yorkers found that, once wartime gasoline rationing ended, Eagle Bridge made a nice excursion destination for a weekend trip. Local residents were usually willing to talk to outsiders about their local celebrity and give directions to her farm. There they would meet the artist, who was a delight to talk to, and either buy or order paintings from her. Songwriter/impresario Cole Porter became a regular customer, ordering several paintings every year to give to friends around Christmas.

In the two-and‑a half decades between picking her paintbrush back up and her death at the age of 101, she produced over 1600 images, always starting with the sky and moving downward to depict tidy fields, well kept houses, and tiny, hard working figures coming together as a community. In the above documentary she alludes to other artists known to depicting “trouble”… such as livestock busting out of their enclosures.

She preferred to document scenes in which everyone was seen to be behaving.

Remarkably, MoMA exhibited Grandma Moses’ work at the same time as Picasso’s Guernica.

In a land and in a life where a woman can grow old with fearlessness and beauty, it is not strange that she should become an artist at the end. — poet Archibald MacLeish

Hmm.

Read Judith Stein’s fascinating essay in its entirety here.

See more of Grandma Moses’ work here, and her portrait on TIME magazine in 1953.

Related Content

How Leo Tolstoy Learned to Ride a Bike at 67, and Other Tales of Lifelong Learning

Free Art & Art History Courses

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.