Deep in the Hundred Acre Wood

Where Christopher Robin plays

You’ll find the enchanted neighborhood

Of Christopher’s childhood days…

Those sweetly sentimental lyrics were penned not by A.A. Milne, creator of Winnie-The-Pooh but rather the Academy-Award winning songwriting team of brothers Robert and Richard Sherman, who also penned the scores of Mary Poppins, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and The Jungle Book.

If you are under the age of 60, chances are your concept of Pooh, Eeyore, Piglet, Kanga, Roo, Owl, Rabbit and Tigger is informed by Winnie the Pooh and Honey Tree, the 1966 Disney cartoon that launched a successful franchise, not E.H. Shepherd’s charming illustrations for the 1926 book, Winnie the Pooh, which entered the public domain this year.

This means that Milne’s work can be freely reproduced or reworked, though Disney retains the copyright to their animated character designs.

Jennifer Jenkins, director of the Center for the Study of the Public Domain at Duke University, told the Washington Post that the bulk of the inquiries she fielded in the lead up to 2022’s public domain titles becoming available had to do with Winnie the Pooh:

I can’t get over how people are freaking out about Winnie-the-Pooh in a good way. Everyone has a very specific story of the first time they read it or their parents gave them a doll or they [have] stories about their kids…It’s the Ted Lasso effect.We need a window into a world where people or animals behave with decency to one another.”

Ummm…

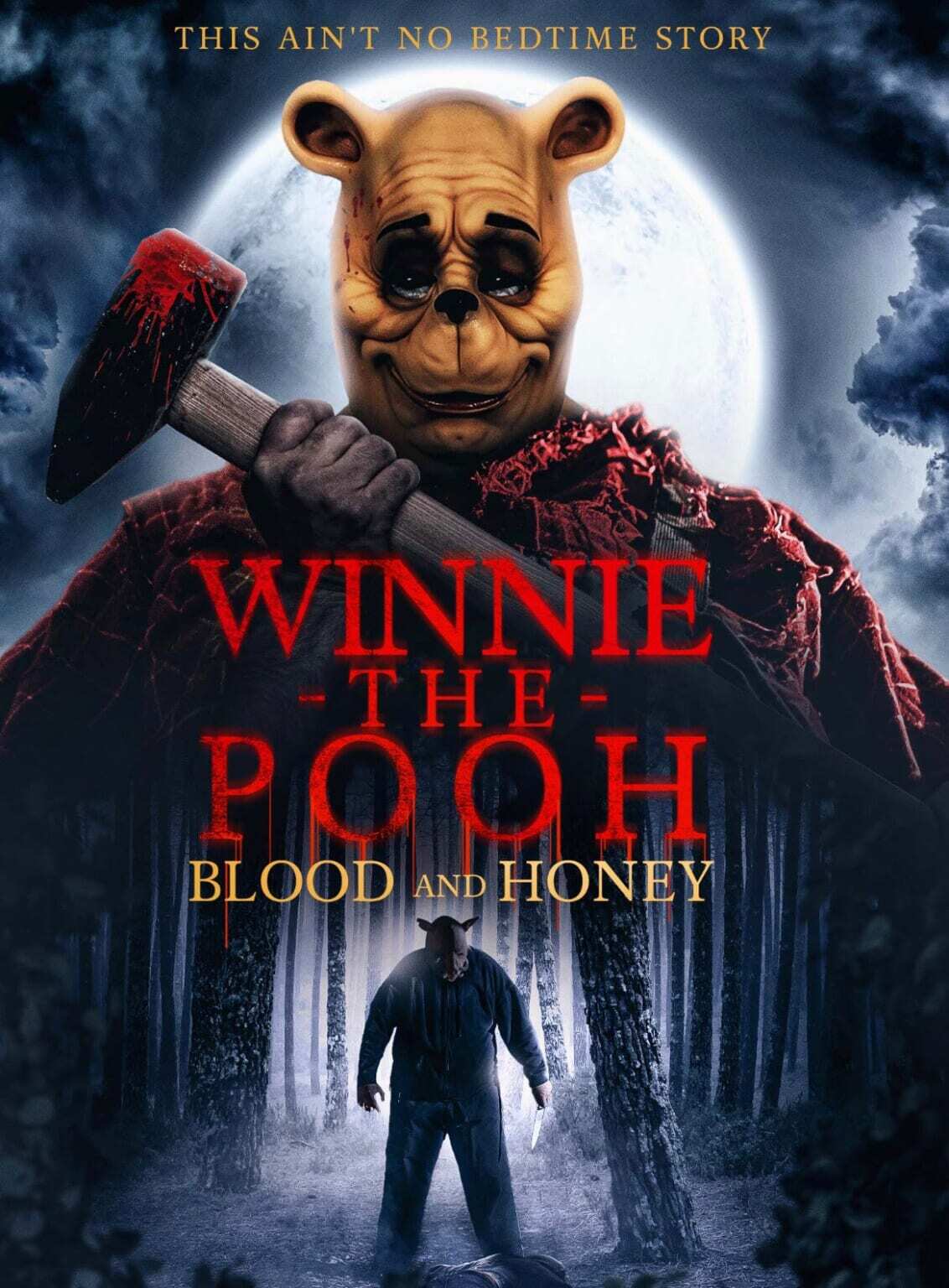

Judging by the trailer for their upcoming live action, low budget feature, Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey, Jagged Edge, a London-based horror production company, is not much interested in Ted Lasso good vibes, though they do manage to stay within the limits of the law, equipping a black clad Piglet with threatening tusks, and dressing the titular “silly old bear” in a red shirt that doesn’t exactly scream Tummy Song.

More like Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Producer-Director Rhys Frake-Waterfield whose as-yet-unreleased credits include Peter Pan’s Neverland Nightmare and Spiders on a Plane told Variety that “we did as much as we could to make sure [the film] was only based on the 1926 version:”

When you see the cover for this and you see the trailers and the stills and all that, there’s no way anyone is going to think this is a child’s version of it.

Here’s hoping he’s right.

The trailer traffics freely in slasher flick tropes:

A bikini clad young woman relaxing, obliviously, in a hot tub.

A hand held camera tracking a desperate, and probably doomed, escape attempt through the woods.

Unnerving warnings written in blood (or possibly honey?)

The childish scrawl on the sign demarcating the 100 Acre Wood is both faithful to the original, and unmistakably sinister.

Equally disturbing is the lettering on Eeyore’s homemade grave marker. (SPOILER: as per Variety, a starving Pooh and Piglet ate him…and apparently discarded a human skull nearby.)

The “enchanted neighborhood of Christopher’s childhood days” has gone decidedly downhill.

Director Frake-Waterfield paints Pooh and Piglet as the primary villains, but surely the college-bound Christopher Robin deserves some of the blame for abandoning his old friends.

On the other hand, when a college-bound Andy tossed his beloved childhood playthings in a giveaway box at the beginning of Toy Story 3, Buzz and Woody did not go on a murderous rampage.

As Frake-Waterfield described Pooh and Piglet’s devolution to HuffPost:

Because they’ve had to fend for themselves so much, they’ve essentially become feral. So they’ve gone back to their animal roots. They’re no longer tame: they’re like a vicious bear and pig who want to go around and try and find prey.

An interview with Dread Central offers a graphic taste of the violent mayhem they inflict, even as Christopher Robin, as clueless as a bikini clad innocent in a hot tub, bleats, “We used to be friends, why are you doing this!?”

Unsurprisingly, the film’s tagline is “This Ain’t No Bedtime Story.”

View production photos, if you dare, here.

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Her allegiance has long been with the 1926 version. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Related Content

Hear the Classic Winnie-the-Pooh Read by Author A.A. Milne in 1929

The Original Stuffed Animals That Inspired Winnie the Pooh