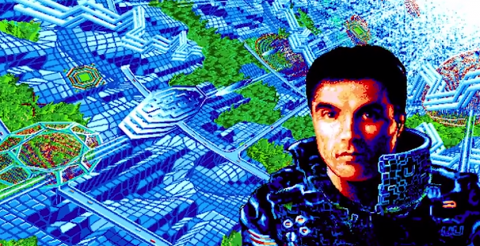

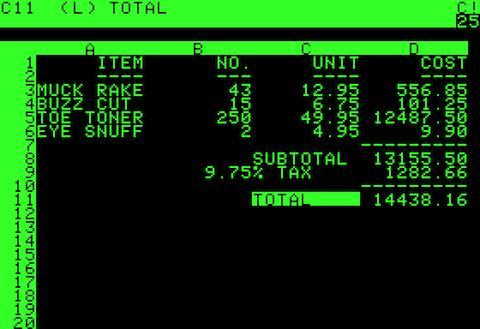

Back in 2009, a startup called Tiny Speck (whose co-founder Stewart Butterfield also co-founded Flickr) launched a multiplayer online video game called Glitch, which won praise for its creative visual style. Although more than 150,000 people played the game, Glitch never quite found its footing in the market. And, in 2012, it was shut down. But, now Glitch rises from the ashes and lives again.

Yesterday Tiny Speck made this announcement:

The entire library of art assets from the game, has been made freely available, dedicated to the public domain.… All of it can be downloaded and used by anyone, for any purpose. (But: use it for good.)

Tiny Speck … has relinquished its ownership of copyright over these 10,000+ assets in the hopes that they help others in their creative endeavours and build on Glitch’s legacy of simple fun, creativity and an appreciation for the preposterous. Go and make beautiful things.

According to Tiny Speck, this release “is intended primarily for developers and those with the technical ability to take advantage of the structured assets.”

Now, assuming you have some tech chops, here are some helpful links that will get you started:

- This public domain release page contains links to the GitHub repositories as well as direct download links for developers.

- The Glitch archive site offers a “comprehensive Encyclopedia of the game world, player archives and snapshots from the game, and more.”

- Above you can watch the videos 17 Fun Things To Do in Glitch in 124 Seconds. This, combined with the Glitch Beta Trailer, will give you a good overview of the game’s visual style.

Long live Glitch!

Related Content:

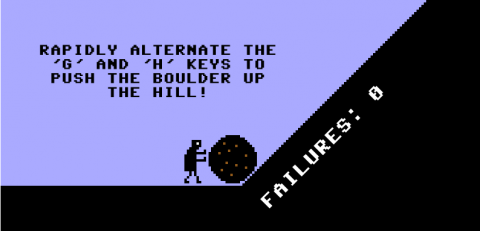

Ancient Greek Punishments: The Retro Video Game