“In 1977, Armistead Maupin wrote a letter to his parents that he had been composing for half his life,” writes the Guardian’s Tim Adams. “He addressed it directly to his mother, but rather than send it to her, he published it in the San Francisco Chronicle, the paper in which he had made his name with his loosely fictionalised Tales of the City, the daily serial written from the alternative, gay world in which he lived.” The late 1970s saw a final flowering of newspaper-serialized novels, the same form in which Charles Dickens had grown famous nearly a century and a half before. But of all the zeitgeisty stories then told a day at a time in urban centers across America, none has had anything like the lasting impact of San Francisco as envisioned by Maupin.

Much of Tales of the City’s now-acknowledged importance comes from the manner in which Maupin populated that San Francisco with a sexually diverse cast of characters — gay, straight, and everything in between — and presented their lives without moral judgment.

He saved his condemnation for the likes of Anita Bryant, the singer and Florida Citrus Commission spokeswoman who inspired Maupin to write that veiled letter to his own parents when she headed up the anti-homosexual “Save Our Children” political campaign. When Michael Tolliver, one of the series’ main gay characters, discovers that his folks back in Florida have thrown in their lot with Bryant, he responds with an eloquent and long-delayed coming-out that begins thus:

Dear Mama,

I’m sorry it’s taken me so long to write. Every time I try to write you and Papa I realize I’m not saying the things that are in my heart. That would be OK, if I loved you any less than I do, but you are still my parents and I am still your child.

I have friends who think I’m foolish to write this letter. I hope they’re wrong. I hope their doubts are based on parents who love and trust them less than mine do. I hope especially that you’ll see this as an act of love on my part, a sign of my continuing need to share my life with you. I wouldn’t have written, I guess, if you hadn’t told me about your involvement in the Save Our Children campaign. That, more than anything, made it clear that my responsibility was to tell you the truth, that your own child is homosexual, and that I never needed saving from anything except the cruel and ignorant piety of people like Anita Bryant.

I’m sorry, Mama. Not for what I am, but for how you must feel at this moment. I know what that feeling is, for I felt it for most of my life. Revulsion, shame, disbelief — rejection through fear of something I knew, even as a child, was as basic to my nature as the color of my eyes.

You can hear Michael’s, and Maupin’s, full letter read aloud by Sir Ian McKellen in the Letters Live video above. In response to its initial publication, Adams writes, “Maupin had received hundreds of other letters, nearly all of them from readers who had cut out the column, substituted their own names for Michael’s and sent it verbatim to their own parents. Maupin’s Letter to Mama has since been set to music three times and become ‘a standard for gay men’s choruses around the world.’ ”

Those words come from a piece on Maupin’s autobiography Logical Family, published just last year, in which the Tales of the City author tells of his own coming out as well as his friendships with other non-straight cultural icons, one such icon being McKellen himself. “I have many regrets about not having come out earlier,” McKellen told BOMB magazine in 1998, “but one of them might be that I didn’t engage myself in the politicking.” He’d come out ten years before, as a stand in opposition to Section 28 of the Local Government Bill, then under consideration in the British Parliament, which prohibited local authorities from depicting homosexuality “as a kind of pretended family relationship.”

McKellen entered the realm of activism in earnest after choosing that moment to reveal his sexual orientation on the BBC, which he did on the advice of Maupin and other friends. A few years later he appeared in the television miniseries adaptation of Tales of the City as Archibald Anson-Gidde, a wealthy real-estate and cultural impresario (one, as Maupin puts it, of the city’s “A‑gays”). In the novels, Archibald Anson-Gidde dies closeted, of AIDS, provoking the ire of certain other characters for not having done enough for the cause in life — a charge, thanks in part to the words of Michael Tolliver, that neither Maupin nor McKellen will surely never face.

Related Content:

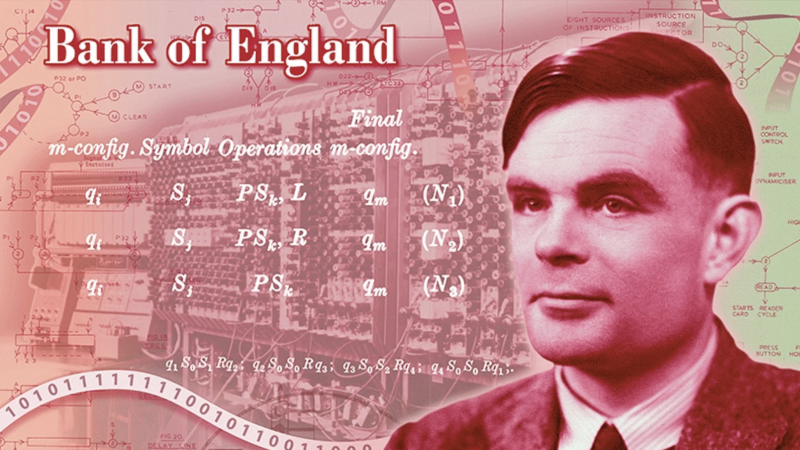

Benedict Cumberbatch Reads a Letter Alan Turing Wrote in “Distress” Before His Conviction For “Gross Indecency”

Allen Ginsberg Talks About Coming Out to His Family & Fellow Poets on 1978 Radio Show (NSFW)

Ian McKellen Reads a Passionate Speech by William Shakespeare, Written in Defense of Immigrants

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.