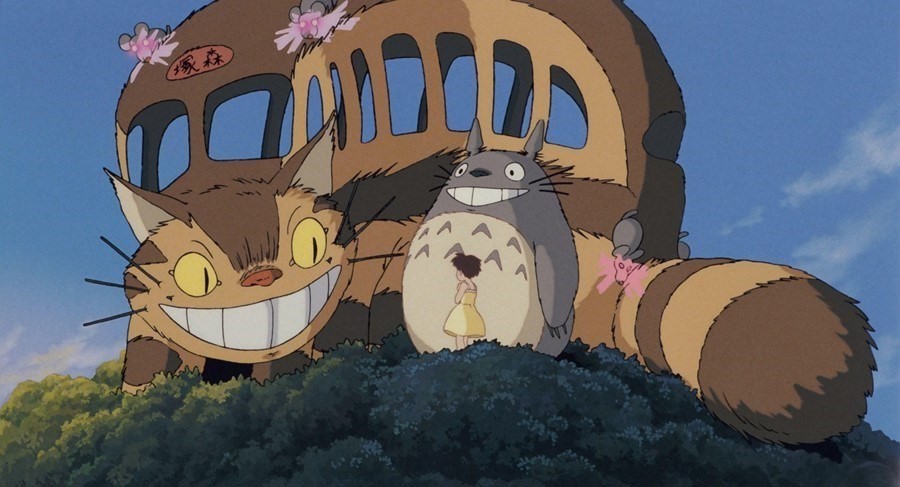

The films of Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli have won immense worldwide acclaim, in large part because they so fully inhabit their medium. Their characters, their stories, their worlds: all can come fully to life only in animation. Still, it’s true that some of their material did originate in other forms. The pre-Ghibli breakout feature Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, for instance, began as a comic book written and drawn by Miyazaki (who at first laid down the condition that it not be adapted for the screen). Four years later, by the time of My Neighbor Totoro, the nature of Ghibli’s visions had become inseparable from that of animation itself.

Now, almost three and a half decades after Totoro’s original release, the production of a stage version is well underway. Playbill’s Raven Brunner reports that the show “will open in London’s West End at The Barbican theatre for a 15-week engagement October 8‑January 21, 2023.

The production will be presented by the Royal Shakespeare Company and executive producer Joe Hisaishi.” Japan’s most famous film composer, Hisaishi scored Totoro as well as all of Miyazaki’s other Ghibli films so far, including Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke, and Spirited Away (itself adapted for the stage in Japan earlier this year).

As you can see in the video just above, the RSC production of Totoro also involves Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. “The puppets being built at Creature Shop are based on designs created by Basil Twist, one of the UK’s most innovative puppeteers,” writes Deadline’s Baz Bamigboye, and they’ll be supplemented by the work of another master, “Mervyn Millar, of Britain’s cutting-edge Significant Object puppet studio.” Even such an assembly of puppet-making expertise will find it a formidable challenge to re-create the denizens of the enchanted countryside in which Totoro’s young protagonists find themselves — to say nothing of the titular wood spirit himself, with all his mass, mischief, and overall benevolence. As for how they’re rigging up the cat bus, Ghibli fans will have to wait until next year to find out.

Related content:

Studio Ghibli Producer Toshio Suzuki Teaches You How to Draw Totoro in Two Minutes

Jim Henson Teaches You How to Make Puppets in Vintage Primer From 1969

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.