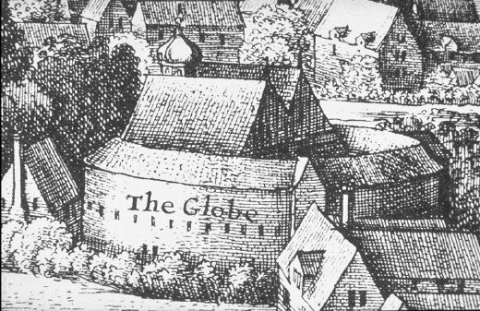

What did Shakespeare’s English sound like to Shakespeare? To his audience? And how can we know such a thing as the phonetic character of the language spoken 400 years ago? These questions and more are addressed in the video above, which profiles a very popular experiment at London’s Globe Theatre, the 1994 reconstruction of Shakespeare’s theatrical home. As linguist David Crystal explains, the theater’s purpose has always been to recapture as much as possible the original look and feel of a Shakespearean production—costuming, music, movement, etc. But until recently, the Globe felt that attempting a play in the original pronunciation would alienate audiences. The opposite proved to be true, and people clamored for more. Above, Crystal and his son, actor Ben Crystal, demonstrate to us what certain Shakespearean passages would have sounded like to their first audiences, and in so doing draw out some subtle wordplay that gets lost on modern tongues.

Shakespeare’s English is called by scholars Early Modern English (not, as many students say, “Old English,” an entirely different, and much older language). Crystal dates his Shakespearean early modern to around 1600. (In his excellent textbook on the subject, linguist Charles Barber bookends the period roughly between 1500 and 1700.) David Crystal cites three important kinds of evidence that guide us toward recovering early modern’s original pronunciation (or “OP”).

1. Observations made by people writing on the language at the time, commenting on how words sounded, which words rhyme, etc. Shakespeare contemporary Ben Jonson tells us, for example, that speakers of English in his time and place pronounced the “R” (a feature known as “rhoticity”). Since, as Crystal points out, the language was evolving rapidly, and there wasn’t only one kind of OP, there is a great deal of contemporary commentary on this evolution, which early modern writers like Jonson had the chance to observe firsthand.

2. Spellings. Unlike today’s very frustrating tension between spelling and pronunciation, Early Modern English tended to be much more phonetic and words were pronounced much more like they were spelled, or vice versa (though spelling was very irregular, a clue to the wide variety of regional accents).

3. Rhymes and puns which only work in OP. The Crystals demonstrate the important pun between “loins” and “lines” (as in genealogical lines) in Romeo and Juliet, which is completely lost in so-called “Received Pronunciation” (or “proper” British English). Two-thirds of Shakespeare’s sonnets, the father and son team claim, have rhymes that only work in OP.

Not everyone agrees on what Shakespeare’s OP might have sounded like. Eminent Shakespeare director Trevor Nunn claims that it might have sounded more like American English does today, suggesting that the language that migrated across the pond retained more Elizabethan characteristics than the one that stayed home.

You can hear an example of this kind of OP in the recording from Romeo and Juliet above. Shakespeare scholar John Barton suggests that OP would have sounded more like modern Irish, Yorkshire, and West Country pronunciations, an accent that the Crystals seem to favor in their interpretations of OP and is much more evident in the reading from Macbeth below (both audio examples are from a CD curated by Ben Crystal).

Whatever the conjecture, scholars tend to use the same set of criteria David Crystal outlines. I recall my own experience with Early Modern English pronunciation in an intensive graduate course on the history of the English language. Hearing a class of amateur linguists read familiar Shakespeare passages in what we perceived as OP—using our phonological knowledge and David Crystal’s criteria—had exactly the effect Ben Crystal described in an NPR interview:

If there’s something about this accent, rather than it being difficult or more difficult for people to understand … it has flecks of nearly every regional U.K. English accent, and indeed American and in fact Australian, too. It’s a sound that makes people — it reminds people of the accent of their home — and so they tend to listen more with their heart than their head.

In other words, despite the strangeness of the accent, the language can sometimes feel more immediate, more universal, and more of the moment, even, than the sometimes stilted, pretentious ways of reading Shakespeare in the accent of a modern London stage actor or BBC news anchor.

For more on this subject, don’t miss this related post: Hear What Hamlet, Richard III & King Lear Sounded Like in Shakespeare’s Original Pronunciation.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

A 68 Hour Playlist of Shakespeare’s Plays Being Performed by Great Actors: Gielgud, McKellen & More

Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour Sings Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18

A Survey of Shakespeare’s Plays (Free Course)

Shakespeare’s Satirical Sonnet 130, As Read By Stephen Fry

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness