Goodbye, Norma Jean…

Marilyn Monroe’s stardom is truly legendary. Her image generates millions of dollars annually. From high-end memorabilia to lunchboxes, fridge magnets, and other cheap trinkets, the world still can’t get enough of her, nearly fifty-five years after her death.

Her acting talent was considerable, but by and large that is not what she’s celebrated for. Speaking at her funeral, her mentor Lee Strasberg, the Artistic Director of the Actors Studio, lamented that “the public who loved her did not have the opportunity to see her as we did, in many of the roles that foreshadowed what she would have become.” In his opinion, the movie star’s true destiny pegged her to become “one of the finest American stage actresses of all time.”

Actor Martin Landau remembered Monroe steeling herself to get up in front of her Actors Studio classmates for the first time, in a scene from Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie with Maureen Stapleton.

Alas, this is not the sort of Monroe moment posterity preserves on a beach tote or sequined t‑shirt.

Strasberg’s moving 1962 eulogy, above, acknowledged both the 31 intimates invited to her final send off, and the crowds outside the gate. Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sammy Davis, Jr. were among the luminaries denied entry. Monroe’s former husband, baseball great Joe DiMaggio banned a whole pantheon of Hollywood movers and shakers, along with the public.

“If it wasn’t for them, she’d still be here,” he told her lawyer, Mickey Rudin.

Studio execs had little regard for the actress’ wellbeing, but Strasberg was both teacher and father figure, allowing her beyond the usual professional boundaries to become a de facto, if problematic, member of the family. As his daughter, Monroe’s friend, actress Susan Strasberg wrote:

Marilyn broke all the rules I was expected to follow. She was unpredictable, but he didn’t yell at her. He constantly validated her. With her, Pop was vulnerable, paternal, permissive. With me he was impersonal, critical, forbidding. What was I doing wrong? Why didn’t he give me permission to be myself as he did her?”

DiMaggio had originally hoped that poet Carl Sandburg might be available to orate at Monroe’s funeral. When Sandburg declined due to ill health, the sad duty fell to Strasberg, who turned out to be uniquely prepared to fulfill this role.

The complete text of Lee Strasberg’s eulogy for Marilyn Monroe is below, as is a short documentary on her involvement with the Actors Studio.

Marilyn Monroe was a legend.

In her own lifetime she created a myth of what a poor girl from a deprived background could attain. For the entire world she became a symbol of the eternal feminine.

But I have no words to describe the myth and the legend. I did not know this Marilyn Monroe. We gathered here today, knew only Marilyn – a warm human being, impulsive and shy, sensitive and in fear of rejection, yet ever avid for life and reaching out for fulfillment. I will not insult the privacy of your memory of her – a privacy she sought and treasured – by trying to describe her whom you knew to you who knew her. In our memories of her she remains alive, not only a shadow on the screen or a glamorous personality.

For us Marilyn was a devoted and loyal friend, a colleague constantly reaching for perfection. We shared her pain and difficulties and some of her joys. She was a member of our family. It is difficult to accept the fact that her zest for life has been ended by this dreadful accident.

Despite the heights and brilliance she attained on the screen, she was planning for the future; she was looking forward to participating in the many exciting things which she planned. In her eyes and in mine her career was just beginning.

The dream of her talent, which she had nurtured as a child, was not a mirage. When she first came to me I was amazed at the startling sensitivity which she possessed and which had remained fresh and undimmed, struggling to express itself despite the life to which she had been subjected.

Others were as physically beautiful as she was, but there was obviously something more in her, something that people saw and recognized in her performances and with which they identified. She had a luminous quality – a combination of wistfulness, radiance, yearning – to set her apart and yet make everyone wish to be a part of it, to share in the childish naïveté which was so shy and yet so vibrant.

This quality was even more evident when she was in the stage. I am truly sorry that the public who loved her did not have the opportunity to see her as we did, in many of the roles that foreshadowed what she would have become. Without a doubt she would have been one of the really great actresses of the stage.

Now it is at an end. I hope her death will stir sympathy and understanding for a sensitive artist and a woman who brought joy and pleasure to the world.

I cannot say goodbye. Marilyn never liked goodbyes, but in the peculiar way she had of turning things around so that they faced reality – I will say au revoir. For the country to which she has gone, we must all someday visit.

Related Content:

Marilyn Monroe Recounts Her Harrowing Experience in a Psychiatric Ward in a 1961 Letter

A Look Inside Marilyn Monroe’s Personal Library

Marilyn Monroe Explains Relativity to Albert Einstein (in a Nicolas Roeg Movie)

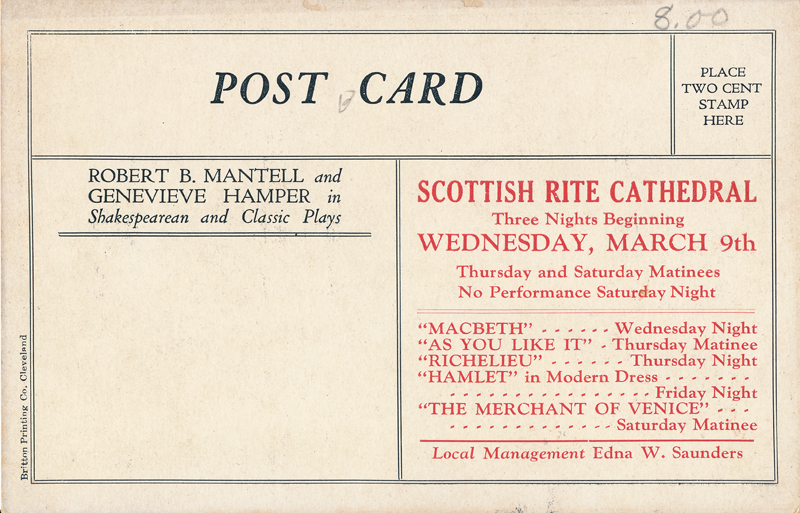

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.