We may take it for granted that the earliest writing systems developed with the Sumerians around 3400 B.C.E. The archaeological evidence so far supports the theory. But it may also be possible that the earliest writing systems predate 5000-year-old cuneiform tablets by several thousand years. And what’s more, it may be possible, suggests paleoanthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger, that those prehistoric forms of writing, which include the earliest known hashtag marks, consisted of symbols nearly as universal as emoji.

The study of symbols carved into cave walls all over the world—including penniforms (feather shapes), claviforms (key shapes), and hand stencils—could eventually push us to “abandon the powerful narrative,” writes Frank Jacobs at Big Think, “of history as total darkness until the Sumerians flip the switch.” Though the symbols may never be truly decipherable, their purposes obscured by thousands of years of separation in time, they clearly show humans “undimming the light many millennia earlier.”

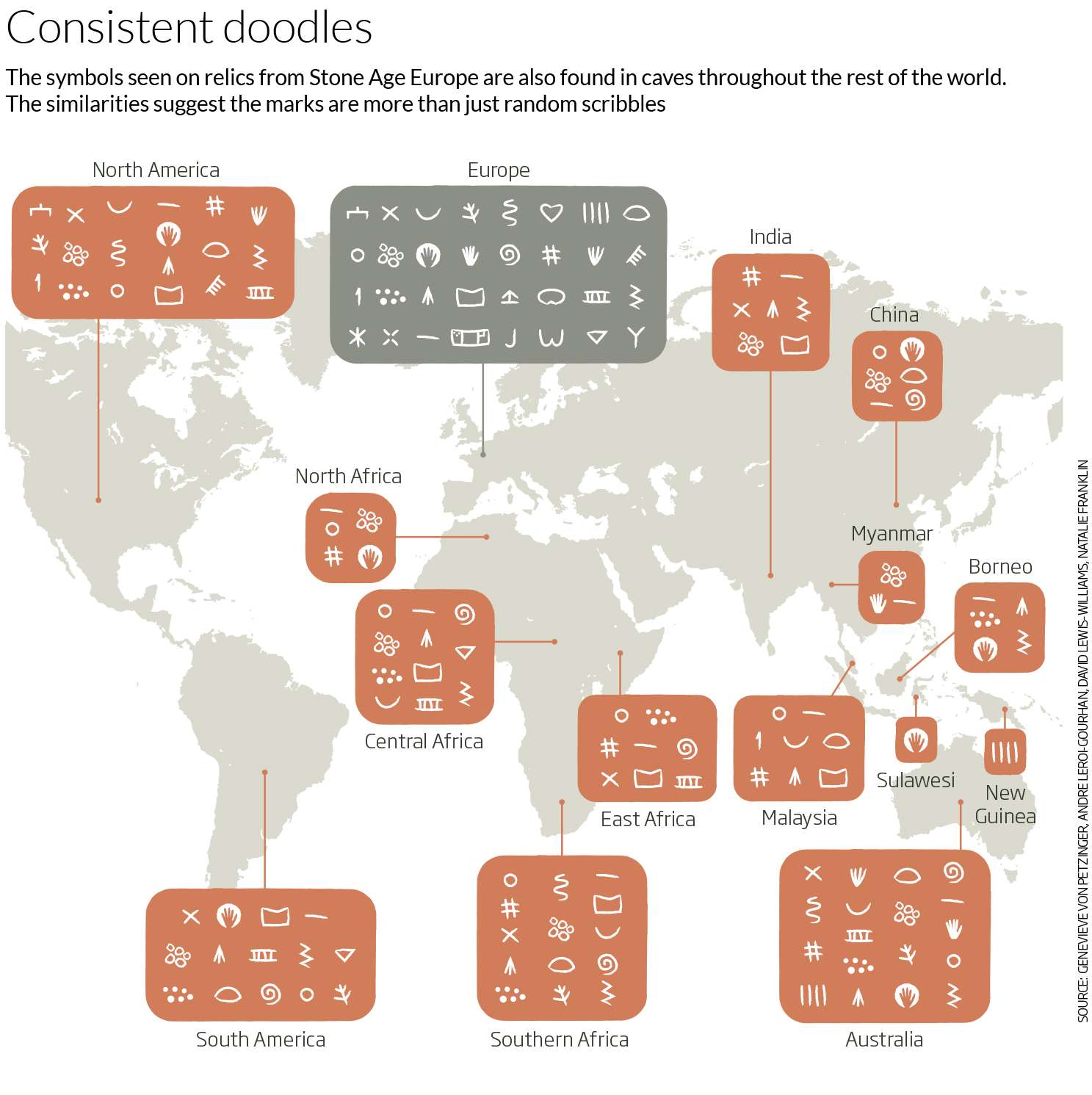

While burrowing deep underground to make cave paintings of animals, early humans as far back as 40,000 years ago also developed a system of signs that is remarkably consistent across and between continents. Von Petzinger spent years cataloguing these symbols in Europe, visiting “52 caves,” reports New Scientist’s Alison George, “in France, Span, Italy and Portugal. The symbols she found ranged from dots, lines, triangles, squares and zigzags to more complex forms like ladder shapes, hand stencils, something called a tectiform that looks a bit like a post with a roof, and feather shapes called penniforms.”

She discovered 32 signs found all over the continent, carved and painted over a very long period of time. “For tens of thousands of years,” Jacobs points out, “our ancestors seem to have been curiously consistent with the symbols they used.” Von Petzinger sees this system as a carryover from modern humans’ migration into Europe from Africa. “This does not look like the start-up phase of a brand-new invention,” she writes in her book The First Signs: Unlocking the mysteries of the world’s oldest symbols.

In her TED Talk at the top, von Petzinger describes this early system of communication through abstract signs as a precursor to the “global network of information exchange” in the modern world. “We’ve been building on the mental achievements of those who came before us for so long,” she says, “that it’s easy to forget that certain abilities haven’t already existed,” long before the formal written records we recognize. These symbols traveled: they aren’t only found in caves, but also etched into deer teeth strung together in an ancient necklace.

Von Petzinger believes, writes George, that “the simple shapes represent a fundamental shift in our ancestor’s mental skills,” toward using abstract symbols to communicate. Not everyone agrees with her. As the Bradshaw Foundation notes, when it comes to the European symbols, eminent prehistorian Jean Clottes argues “the signs in the caves are always (or nearly always) associated with animal figures and thus cannot be said to be the first steps toward symbolism.”

Of course, it’s also possible that both the signs and the animals were meant to convey ideas just as a written language does. So argues MIT linguist Cora Lesure and her co-authors in a paper published in Frontiers in Psychology last year. Cave art might show early humans “converting acoustic sounds into drawings,” notes Sarah Gibbens at National Geographic. Lesure says her research “suggests that the cognitive mechanisms necessary for the development of cave and rock art are likely to be analogous to those employed in the expression of the symbolic thinking required for language.”

In other words, under her theory, “cave and rock [art] would represent a modality of linguistic expression.” And the symbols surrounding that art might represent an elaboration on the theme. The very first system of writing, shared by early humans all over the world for tens of thousands of years.

via Big Think

Related Content:

Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema?

Discover the Oldest Beer Recipe in History From Ancient Sumeria, 1800 B.C.

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness