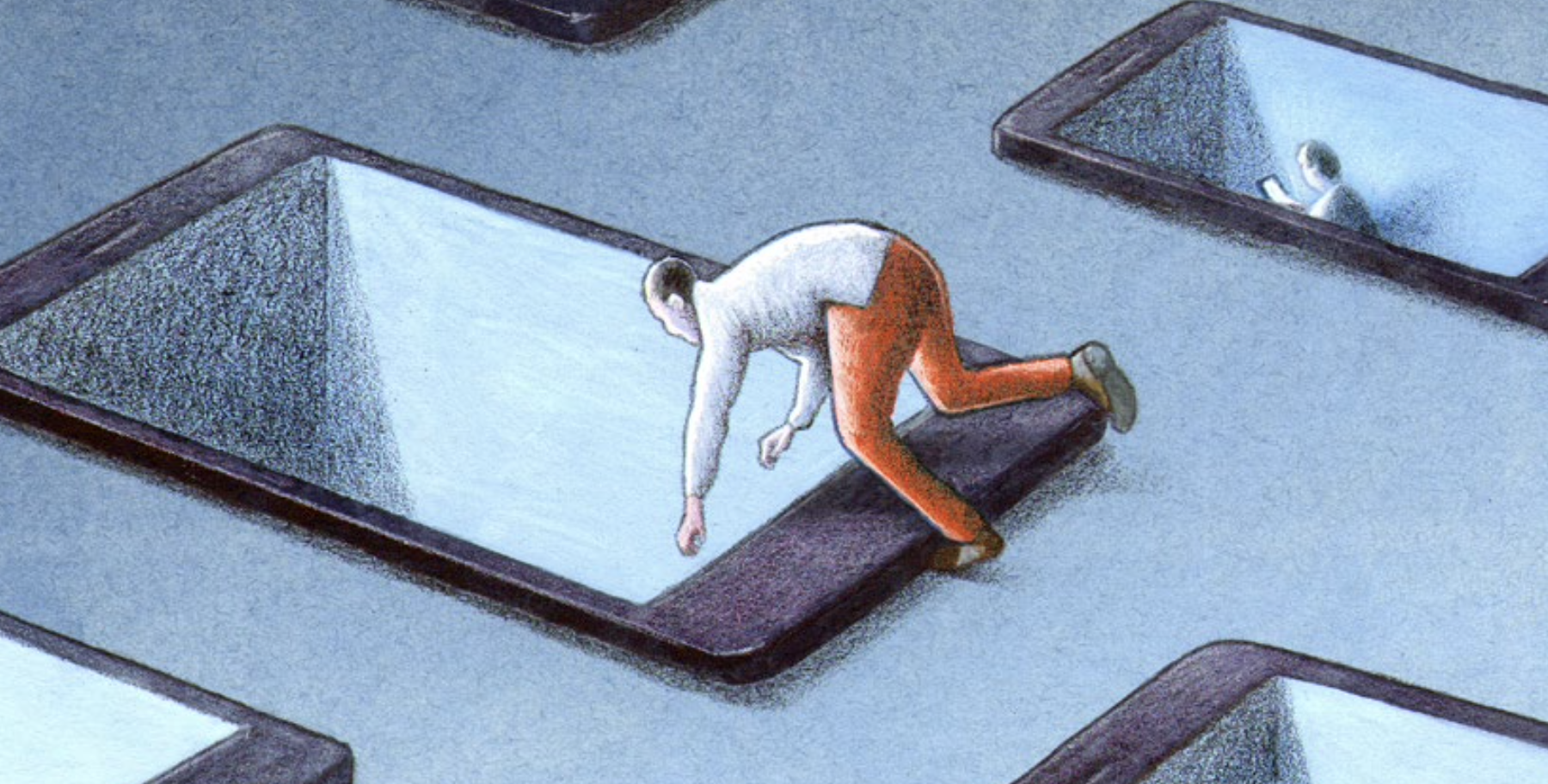

The technology we put between ourselves and others tends to always create additional strains on communication, even as it enables near-constant, instant contact. When it comes to our now-primary mode of interacting — staring at each other as talking heads or Brady Bunch-style galleries — those stresses have been identified by communication experts as “Zoom fatigue,” now a subject of study among psychologists who want to understand our always-connected-but-mostly-isolated lives in the pandemic, and a topic for Today show segments like the one above.

As Stanford researcher Jeremy Bailenson vividly explains to Today, Zoom fatigue refers to the burnout we experience from interacting with dozens of people for hours a day, months on end, through pretty much any video conferencing platform. (But, let’s face it, mostly Zoom.) We may be familiar with the symptoms already if we spend some part of our day on video calls or lessons. Zoom fatigue combines the problems of overwork and technological overstimulation with unique forms of social exhaustion that do not plague us in the office or the classroom.

Bailenson, director of Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, refers to this kind of burnout as “Nonverbal Overload,” a collection of “psychological consequences” from prolonged periods of disembodied conversation. He has been studying virtual communication for two decades and began writing about the current problem in April of 2020 in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that warned, “software like Zoom was designed to do online work, and the tools that increase productivity weren’t meant to mimic normal social interaction.”

Now, in a new scholarly article published in the APA journal Technology, Mind, and Behavior, Bailenson elaborates on the argument with a focus on Zoom, not to “vilify the company,” he writes, but because “it has become the default platform for many in academia” (and everywhere else, perhaps its own form of exhaustion). The constituents of nonverbal overload include gazing into each others’ eyes at close proximity for long periods of time, even when we aren’t speaking to each other.

Anyone who speaks for a living understands the intensity of being stared at for hours at a time. Even when speakers see virtual faces instead of real ones, research has shown that being stared at while speaking causes physiological arousal (Takac et al., 2019). But Zoom’s interface design constantly beams faces to everyone, regardless of who is speaking. From a perceptual standpoint, Zoom effectively transforms listeners into speakers and smothers everyone with eye gaze.

On Zoom, we also have to expend much more energy to send and interpret nonverbal cues, and without the context of the room outside the screen, we are more apt to misinterpret them. Depending on the size of our screen, we may be staring at each other as larger-than-life talking heads, a disorienting experience for the brain and one that lends more impact to facial expressions than may be warranted, creating a false sense of intimacy and urgency. “When someone’s face is that close to ours in real life,” writes Vignesh Ramachandran at Stanford News, “our brains interpret it as an intense situation that is either going to lead to mating or to conflict.”

Unless we turn off the view of ourselves on the screen — which we generally don’t do because we’re conscious of being stared at — we are also essentially sitting in front of a mirror while trying to focus on others. The constant self-evaluation adds an additional layer of stress and taxes the brain’s resources. In face-to-face interactions, we can let our eyes wander, even move around the room and do other things while we talk to people. “There’s a growing research now that says when people are moving, they’re performing better cognitively,” says Bailenson. Zoom interactions, conversely, can inhibit movement for long periods of time.

“Zoom fatigue” may not be as dire as it sounds, but rather the inevitable trials of a transitional period, Bailenson suggests. He offers solutions we can implement now: using the “hide self-view” button, muting our video regularly, setting up the technology so that we can fidget, doodle, and get up and move around.… Not all of these are going to work for everyone — we are, after all, socialized to sit and stare at each other on Zoom; refusing to participate might send unintended messages we would have to expend more energy to correct. Bailenson further describes the phenomenon in the BBC Business Daily podcast interview above.

“Videoconferencing is here to stay,” Bailenson admits, and we’ll have to adapt. “As media psychologists it is our job,” he writes to his colleagues in the new article, to help “users develop better use practices” and help “technologists build better interfaces.” He mostly leaves it to the technologists to imagine what those are, though we ourselves have more control over the platform than we collectively acknowledge. Could we maybe admit, Bailenson writes, that “perhaps a driver of Zoom fatigue is simply that we are taking more meetings than we would be doing face-to-face”?

Read about the “Zoom Exhaustion & Fatigue Scale (ZEF Scale)” developed by Bailenson and his colleagues at Stanford and the University of Gothenburg here. Then take the survey yourself, and see where you rank in the ZEF categories of general fatigue, visual fatigue, social fatigue, motivational fatigue, and emotional fatigue.

Related Content:

How Information Overload Robs Us of Our Creativity: What the Scientific Research Shows

In 1896, a French Cartoonist Predicted Our Socially-Distanced Zoom Holiday Gatherings

Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli Releases Free Backgrounds for Virtual Meetings: Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness