Mushrooms are justly celebrated as virtuous multitaskers.

They’re food, teachers, movie stars, design inspiration…

…and some, as anyone who’s spent time playing or watching The Last of Us can readily attest, are killers.

Hopefully we’ve got some time before civilization is conquered by zombie cordyceps.

For now, the ones to watch out for are amanita phalloide, aka death cap mushrooms.

The powerful amatoxin they harbor is behind 90 percent of mushroom-related fatalities worldwide. It causes severe liver damage, leading to bleeding disorders, brain swelling, and multi-organ failure in those who survive.

A death cap took the life of a three-year-old in British Columbia who mistook one for a tasty straw mushroom on a foraging expedition with his family near their apartment complex.

In Melbourne, a pot pie that tested positive for death caps resulted in the deaths of three adults, and sent a fourth to the hospital in critical condition.

As the animators feast on mushrooms’ limitless visual appeal in the above episode of The Atlantic’s Life Up Close series, author Craig Childs delivers some sobering news:

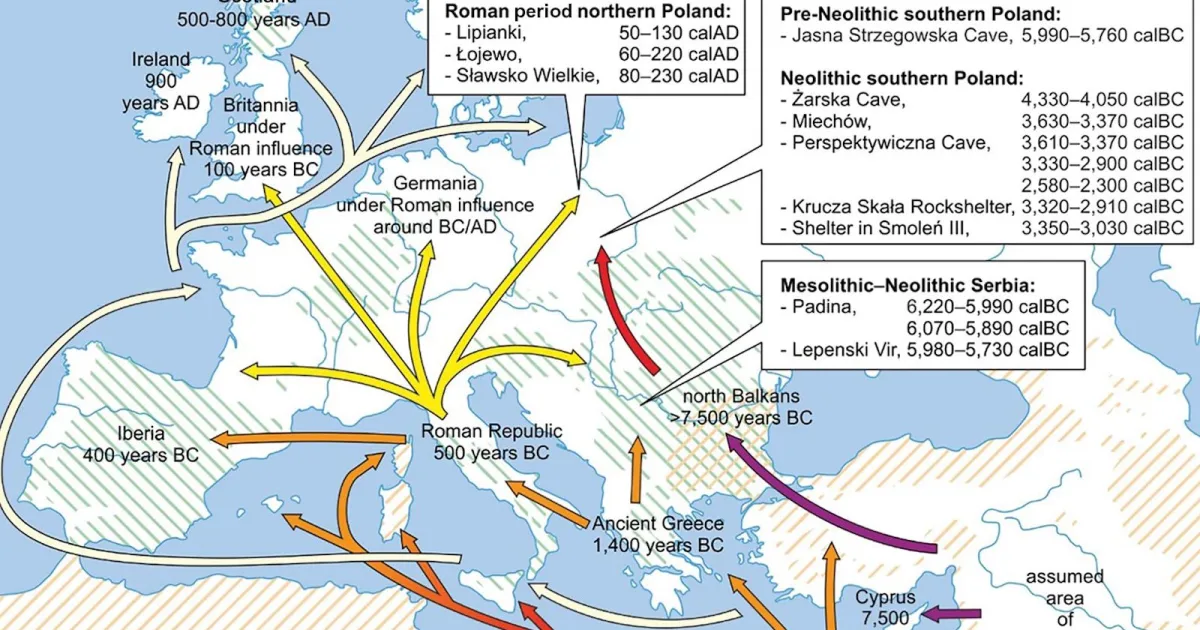

We did it to ourselves. Humans are the ones who’ve enabled death caps to spread so far beyond their native habitats in Scandinavia and parts of northern Europe, where the poisonous fungi feed on the root tips of deciduous trees, springing up around their hosts in tidy fairy rings.

When other countries import these trees to beautify their city streets, the death caps, whose fragile spores are incapable of traveling long distances when left to their own devices, tag along.

They have sprouted in the Pacific Northwest near imported sweet chestnuts, beeches, hornbeams, lindens, red oaks, and English oaks, and other host species.

As biochemist Paul Kroeger, cofounder of the Vancouver Mycological Society, explained in a 2019 article Childs penned for the Atlantic, the invasive death caps aren’t popping up in deeply wooded areas.

Rather, they are settling into urban neighborhoods, frequently in the grass strips bordering sidewalks. When Childs accompanied Krueger on his rounds, the first of two dozen death caps discovered that day were found in front of a house festooned with Halloween decorations.

Now that they have established themselves, the death caps cannot be rousted. No longer mere tourists, they’ve been seen making the jump to native oaks in California and Western Canada.

Childs also notes that death caps are no longer a North American problem:

They have spread worldwide where foreign trees have been introduced into landscaping and forestry practices: North and South America, New Zealand, Australia, South and East Africa, and Madagascar. In Canberra, Australia, in 2012, an experienced Chinese-born chef and his assistant prepared a New Year’s Eve dinner that included, unbeknownst to them, locally gathered death caps. Both died within two days, waiting for liver transplants; a guest at the dinner also fell ill, but survived after a successful transplant.

Foragers should proceed with extreme caution.

Related Content

The Beautifully Illustrated Atlas of Mushrooms: Edible, Suspect and Poisonous (1827)

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.