The other day, I found myself reading about what life is like in countries that have successfully minimized the pandemic: worry free holidays, meeting friends and family without the danger of infection, a general air of normalcy thanks to a combination of rigorous public health efforts and public cooperation. I live in the U.S., where the political party currently in power (and desperate to keep it) convinced millions of my fellow citizens that the virus was a hoax, a scam, a political ploy. The reality of a virus-free existence seems like a fairy tale.

But perhaps, after a year of death, suffering, and lunacy, we will begin to see the tide turn once enough people get vaccinated… if we can overcome the massive wave of anti-science bias and disinformation about vaccines…. “The anti-vaccination movement is going to make Covid-19 more difficult to get under control,” says Scott Ratzan, distinguished lecturer at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy.

Long before the vaccine arrived, Katherine O’Brien, a director at WHO, noted there was already a prominent “anti-vaccination voice” on social media. “We have to take this seriously,” she told The BMJ. “Vaccination isn’t just an individual choice; it protects those who can’t be vaccinated.” We’ve seen the term “herd immunity” misused a lot lately. What it essentially means is that a small number of people can be shielded from the virus if the vast majority get vaccinated. Or as WHO puts it, “herd immunity is achieved by protecting people from a virus, not by exposing them to it.”

All of this means there will likely never be a more critical moment to educate ourselves and others on the science of vaccines. We may not sway those faithful to a certain narrative, but it can help shift the conversation from fears of the unknown to the long history of the known when it comes to eradicating highly infectious, deadly diseases. A great way to start is with the basics, which you’ll find in the videos above from TED-Ed, Mechanisms of Medicine, and PBS. Watch them yourself, share them on social media, and keep the conversation about vaccines’ efficacy going.

In the TED-Ed lesson just above, we learn some more specific information about the key phases of developing a new vaccine: exploratory research, clinical testing, and manufacturing. You’ll find much more detailed information on the history of vaccines, spurious anti-vaccination claims, and the coronavirus vaccines now on the market and currently shipping around the world, at the award-winning site, The History of Vaccines, from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

The COVID-19 vaccine is a special kind of vaccine (mRNA) that works differently from most, and you can learn about how it works here. A quick primer on herd immunity appears at the bottom.

Related Content:

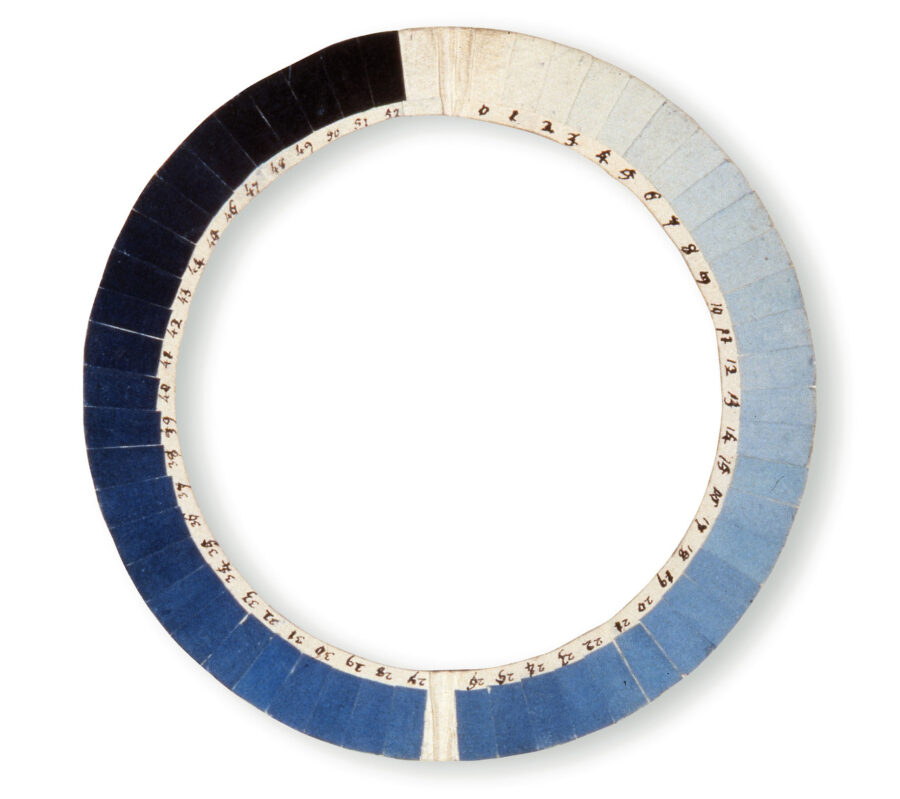

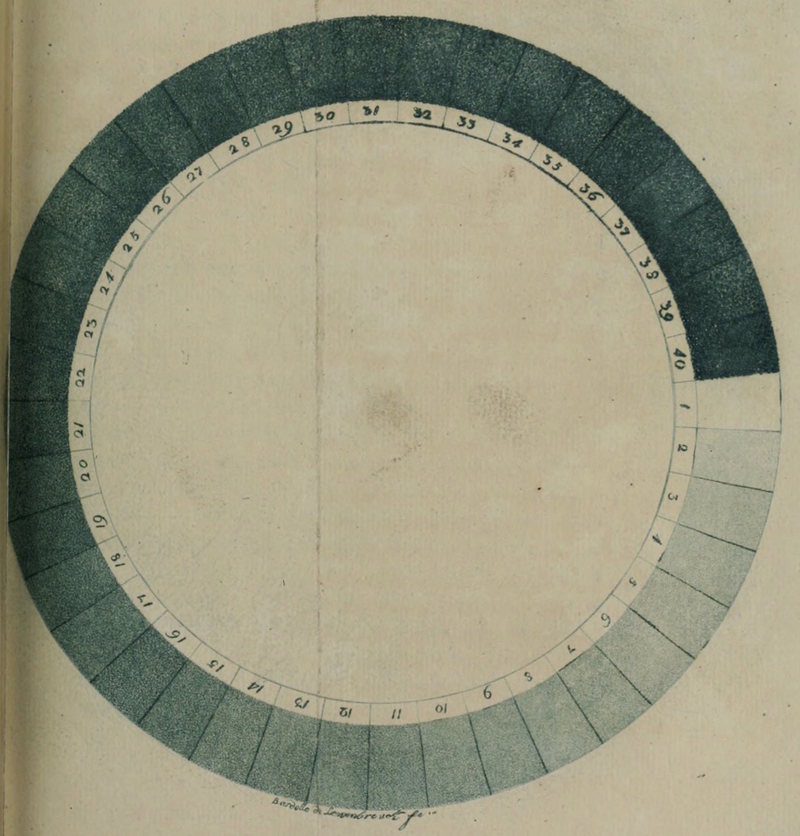

19th Century Maps Visualize Measles in America Before the Miracle of Vaccines

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.