The practice and privilege of academic science has been slow in trickling down from its origins as a pursuit of leisured gentleman. While many a leisured lady may have taken an interest in science, math, or philosophy, most women were denied participation in academic institutions and scholarly societies during the scientific revolution of the 1700s. Only a handful of women — seven known in total — were granted doctoral degrees before the year 1800. It wasn’t until 1678 that a female scholar was given the distinction, some four centuries or so after the doctorate came into being. While several intellectuals and even clerics of the time held progressive attitudes about gender and education, they were a decided minority.

Curiously, four of the first seven women to earn doctoral degrees were from Italy, beginning with Elena Cornaro Piscopia at the University of Padua. Next came Laura Bassi, who earned her degree from the University of Bologna in 1732. There she distinguished herself in physics, mathematics, and natural philosophy and became the first salaried woman to teach at a university (she was at one time the university’s highest paid employee). Bassi was the chief popularizer of Newtonian physics in Italy in the 18th century and enjoyed significant support from the Archbishop of Bologna, Prospero Lambertini, who — when he became Pope Benedict XIV — elected her as the 24th member of an elite scientific society called the Benedettini.

“Bassi was widely admired as an excellent experimenter and one of the best teachers of Newtonian physics of her generation,” says Paula Findlen, Stanford professor of history. “She inspired some of the most important male scientists of the next generation while also serving as a public example of a woman shaping the nature of knowledge in an era in which few women could imagine playing such a role.” She also played the role available to most women of the time as a mother of eight and wife of Giuseppe Veratti, also a scientist.

Bassi was not allowed to teach classes of men at the university — only special lectures open to the public. But in 1740, she was granted permission to lecture at her home, and her fame spread, as Findlen writes at Physics World:

Bassi was widely known throughout Europe, and as far away as America, as the woman who understood Newton. The institutional recognition that she received, however, made her the emblematic female scientist of her generation. A university graduate, salaried professor and academician (a member of a prestigious academy), Bassi may well have been the first woman to have embarked upon a full-fledged scientific career.

Poems were written about Bassi’s successes in demonstrating Newtonian optics; “news of her accomplishments traveled far and wide,” reaching the ear of Benjamin Franklin, whose work with electricity Bassi followed keenly. In Bologna, surprise at Bassi’s achievements was tempered by a culture known for “celebrating female success.” Indeed, the city was “jokingly known as a ‘paradise for women,’” writes Findlen. Bassi’s father was determined that she have an education equal to any of her class, and her family inherited money that had been equally divided between daughters and sons for generations; her sons “found themselves heirs to the property that came to the family through Laura’s maternal line,” notes the Stanford University collection of Bassi’s personal papers.

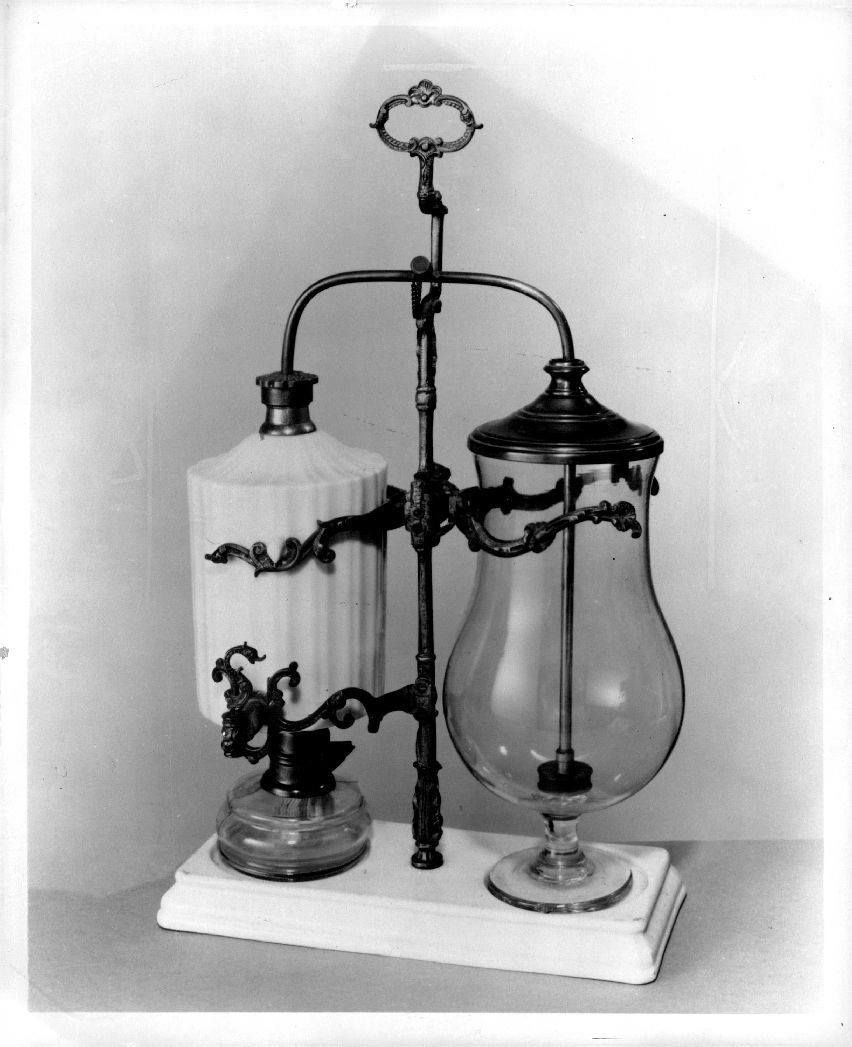

Bassi’s academic work is held at the Academy of Sciences in Bologna. Of the papers that survive, “thirteen are on physics, eleven are on hydraulics, two are on mathematics, one is on mechanics, one is on technology, and one is on chemistry,” writes a University of St. Andrew’s biography. In 1776, a year usually remembered for the formation of a government of leisured men across the Atlantic, Bassi was appointed to the Chair of Experimental Physics at Bologna, an appointment that not only meant her husband became her assistant, but also that she became the “first woman appointed to a chair of physics at any university in the world.”

Bologna was proud of its distinguished daughter, but perhaps still thought of her as an oddity and a token. As Dr. Eleonora Adami notes in a charming biography at sci-fi illustrated stories, the city once struck a medal in her honor, “commemorating her first lecture series with the phrase ‘Soli cui fas vidisse Minervam,’” which translates roughly to “the only one allowed to see Minerva.” But her example inspired other women, like Cristina Roccati, who earned a doctorate from Bologna in 1750, and Dorothea Erxleben, who became the first woman to earn a Doctorate in Medicine four years later at the University of Halle. Such singular successes did not change the patriarchal culture of academia, but they started the trickle that would in time become several branching streams of women succeeding in the sciences.

Related Content:

Jocelyn Bell Burnell Changed Astronomy Forever; Her Ph.D. Advisor Won the Nobel Prize for It

Women Scientists Launch a Database Featuring the Work of 9,000 Women Working in the Sciences

Real Women Talk About Their Careers in Science

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness