A newspaper article about this speech could well be titled: AUTHOR CLAIMS TO HAVE SEEN GOD BUT CAN’T GIVE ACCOUNT OF WHAT HE SAW. — PKD

In 1977, cult writer Philip K. Dick arrived at a science fiction convention in Metz, France to deliver a speech called, “If You Find this World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others.” (Read an edited transcript here.) The audience would leave bewildered, mystified. His talk ranged widely across such topics as cosmological time, the possibility of the universe as a computer simulation, the experience of deja vu, and the oppressive regime of Richard Nixon. It would become a sort of rebus for decoding Dick’s fiction.

If the “Metz address” were only a key to the strange occurrences in novels like A Scanner Darkly, Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, and The Man in the High Castle, it would be an extraordinary document for Philip K. Dick fans.

But just as Dick claimed that the events of his 1981 novel V.A.L.I.S. were real– he had actually had a visionary encounter with “God” after dental surgery in 1974 — so here he claims to have actually experienced, or remembered, multiple realities and, after said encounter, to have recognized them all as true.

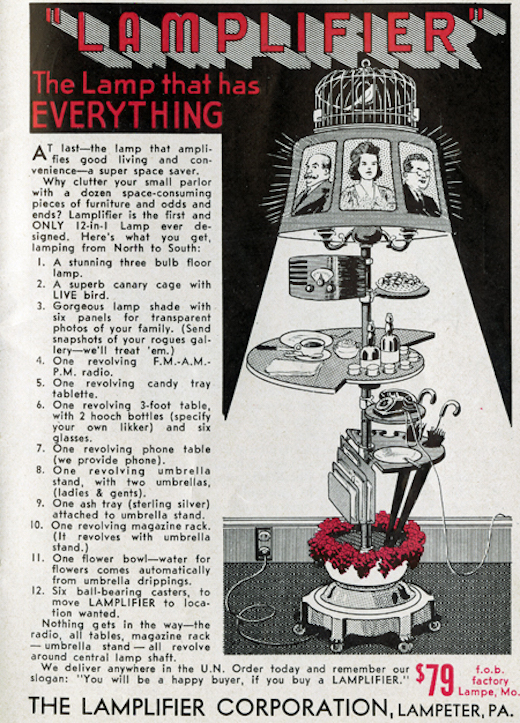

I, in my stories and novels, often write about counterfeit worlds, semi-real worlds, as well as deranged private worlds inhabited, often, by just one person, while, meantime, the other characters either remain in their own worlds throughout or are somehow drawn into one of the peculiar ones. …At no time did I have a theoretical or conscious explanation for my preoccupation with these pluriform pseudoworlds, but now I think I understand. What I was sensing was the manifold or partially actualized realities lying tangent to what evidently is the most actualized one, the one that the majority of us, by consensus gentium, agree on.

“The world of Flow My Tears is an actual (or rather once actual) alternate world, and I remember it in detail. I do not know who else does. Maybe no one else does. perhaps all of you were always — have always been — here. But I was not. In novel after novel, story after story, over a twenty-five year period, I wrote repeatedly about a particular other landscape, a dreadful one. In March 1974, I understood why. …I had good reason to. My novels and stories were, without my realizing it consciously, autobiographical. It was — this return of memory — the most extraordinary experience of my life. …

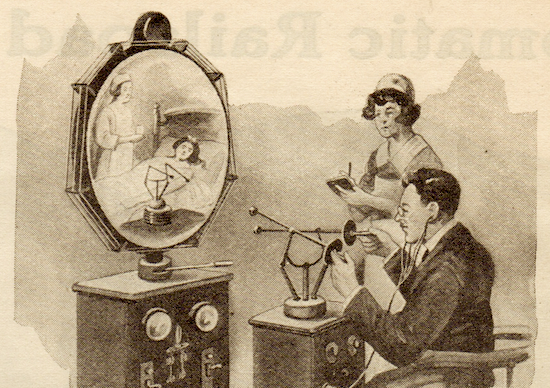

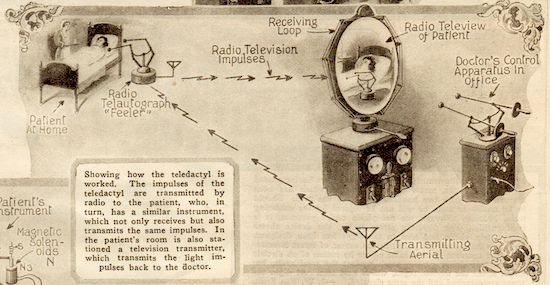

The narrower subject of his speech, Dick says by way of introduction, is “orthogonal time,” or “right-angle time.” To explain this he calls up an image of parallel universes overlapping at the edges of a “lateral axis.” These blend and “come into focus,” as an entity he calls “the Programer-Reprogrammer” changes the variables, while a “counterentity” he calls the “Dark Counterplayer” tries to mess things up. Despite the use of software terms, Dick’s imagery seems to draw as much from chess, or Taoism, as computer science. The interplay of programmer/counterprogrammer is a dialectic, resulting in new syntheses. God is not an independent, self-existent being but something more akin to Atman, “the view of the oldest religion of India, and to some extent… of Spinoza and Alfred North Whitehead …. God within the universe… The Sufi saying [from Rumi] ‘The workman is invisible within the workshop’ applies here.”

We cannot see the workings of this mystical intelligence except when the illusion of seamlessness breaks down and memories of past or alternate lives intrude. These are not memories of a linear time, but of other possible present times, all existing at once just out of focus. Dystopian police states, an alternate present ruled by Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan… These currently exist, Dick says, on the orthogonal line of time, only we cannot see them because the variables, and our memories, have been changed to suit the latest version of reality, a synthesis and updated improvement. However, it’s entirely possible that we’re all experiencing slightly different realities, depending on the “memories” of alternate presents leaking into our experience.

Thus, the talk’s title: not only could the world be worse, he says, but it is currently worse in the multiverse of rejected alternate worlds we can’t (or can’t quite) see. Here, at the end of his speech, Dick gets theological, and teleological, again, claiming to have seen a vision of a “parklike” world that “was not what my Christian training had prepared me for at all.” His description sounds ripped from the cover of a 70s pulp fantasy novel, complete with a naked goddess and an alien “landscape beyond a golden rectangle doorway.” He takes pains to distance his vision from the Christian garden of Eden, but his final remarks sound more like C.S. Lewis than the paranoid, drug-addled conspiracist his audience might have been prepared to meet:

The best I can do …is to play the role of prophet, of ancient prophets and such oracles as the sibyl at Delphi, and to talk of a wonderful garden world, much like that which once our ancestors are said to have inhabited — in fact, I sometimes imagine it to be exactly that same world restored, as if a false trajectory of our world will eventually be fully corrected and once more we will be where once, many thousands of years ago, we lived and were happy.

…I believe I know a great secret. When the work of restoration is completed, we will not even remember the tyrannies, the cruel barbarisms of the Earth we inhabited… the vast body of pain and grief and loss and disappointment within us will be expunged as if it had never been. I believe that process is taking place now, has always been taking place now. And, mercifully, we are already being permitted to forget that which formerly was. And perhaps in my novels and stories I have done wrong to urge you to remember.

Was Philip K. Dick out of his mind? He sounds perfectly lucid in other interviews he gave at the same time, and dismisses the notion that his ideas are the product of mental illness. Travis Diehl writes at Art Papers that Dick has come to seem more like an actual than a self-styled prophet in the decades since this interview, and his “paranoia comes to seem more and more like prescience,” foreseeing the major themes of The Matrix, Jean Baudrillard’s postmodern classic Simulacra and Simulation, and favorite philosopher of Silicon Valley Nick Bostrom.

Whatever the source of the author’s experiences, “the rupture that pushed Dick’s life toward a knowledge of other worlds — towards gnosis — was an aesthetic one: Dick’s visions appeared accompanied, or induced, by art,” and it was only by means of art that he claimed to apprehend them. “Our God is the deus absconditus: the hidden god.” We cannot know what it is, he says. But this does not exempt us from the making and remaking of the world. No one is — to use a current term of art — a non-playable character. “Concealed though the form is,” Dick says, “the latter will confront us; we are involved in it — in fact, we are instruments by which it is accomplished.”

Related Content:

Hear VALIS, an Opera Based on Philip K. Dick’s Metaphysical Novel

Robert Crumb Illustrates Philip K. Dick’s Infamous, Hallucinatory Meeting with God (1974)

The Penultimate Truth About Philip K. Dick: Documentary Explores the Mysterious Universe of PKD

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness