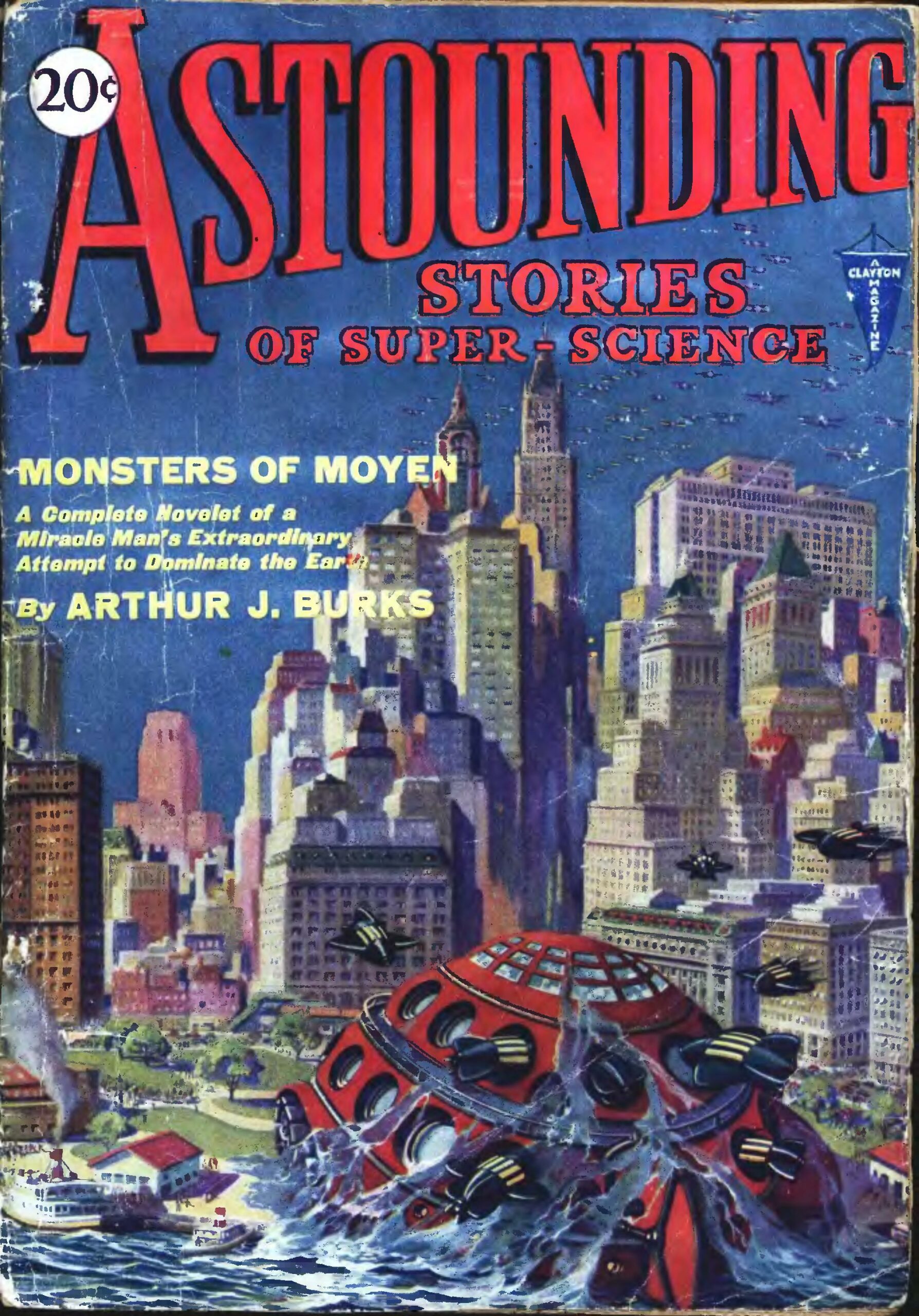

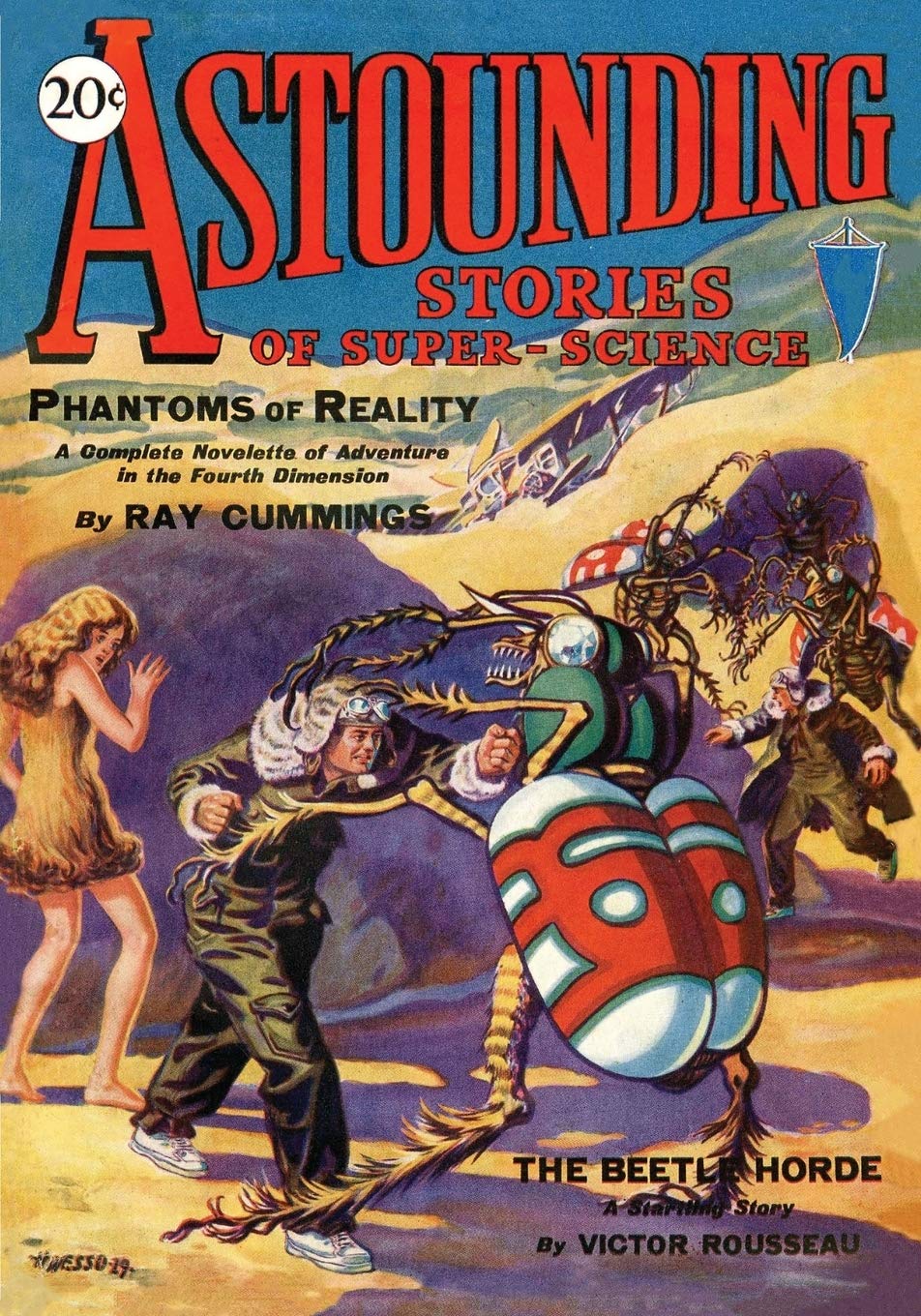

Having been putting out issues for 92 years now, Analog Science Fiction and Fact stands as the longest continuously published magazine of its genre. It also lays claim to having developed or at least popularized that genre in the form we know it today. When it originally launched in December of 1929, it did so under the much more whiz-bang title of Astounding Stories of Super-Science. But only three years later, after a change of ownership and the installation as editor of F. Orlin Tremaine, did the magazine begin publishing work by writers remembered today as the defining minds of science fiction.

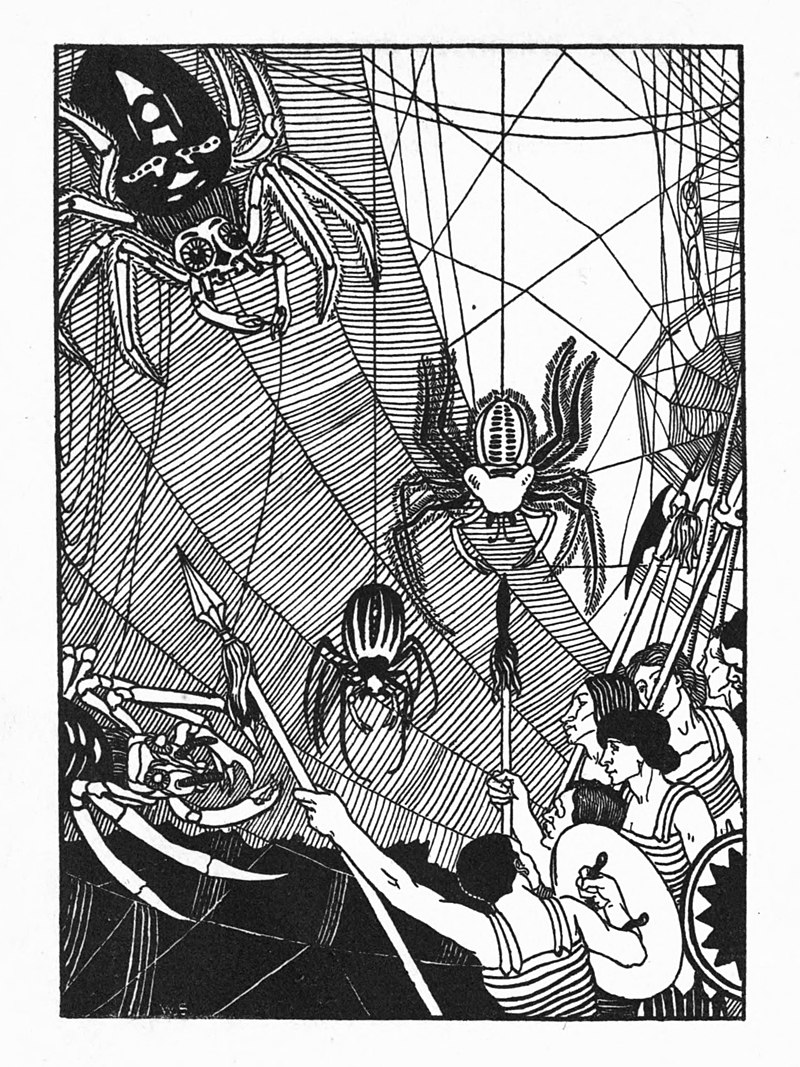

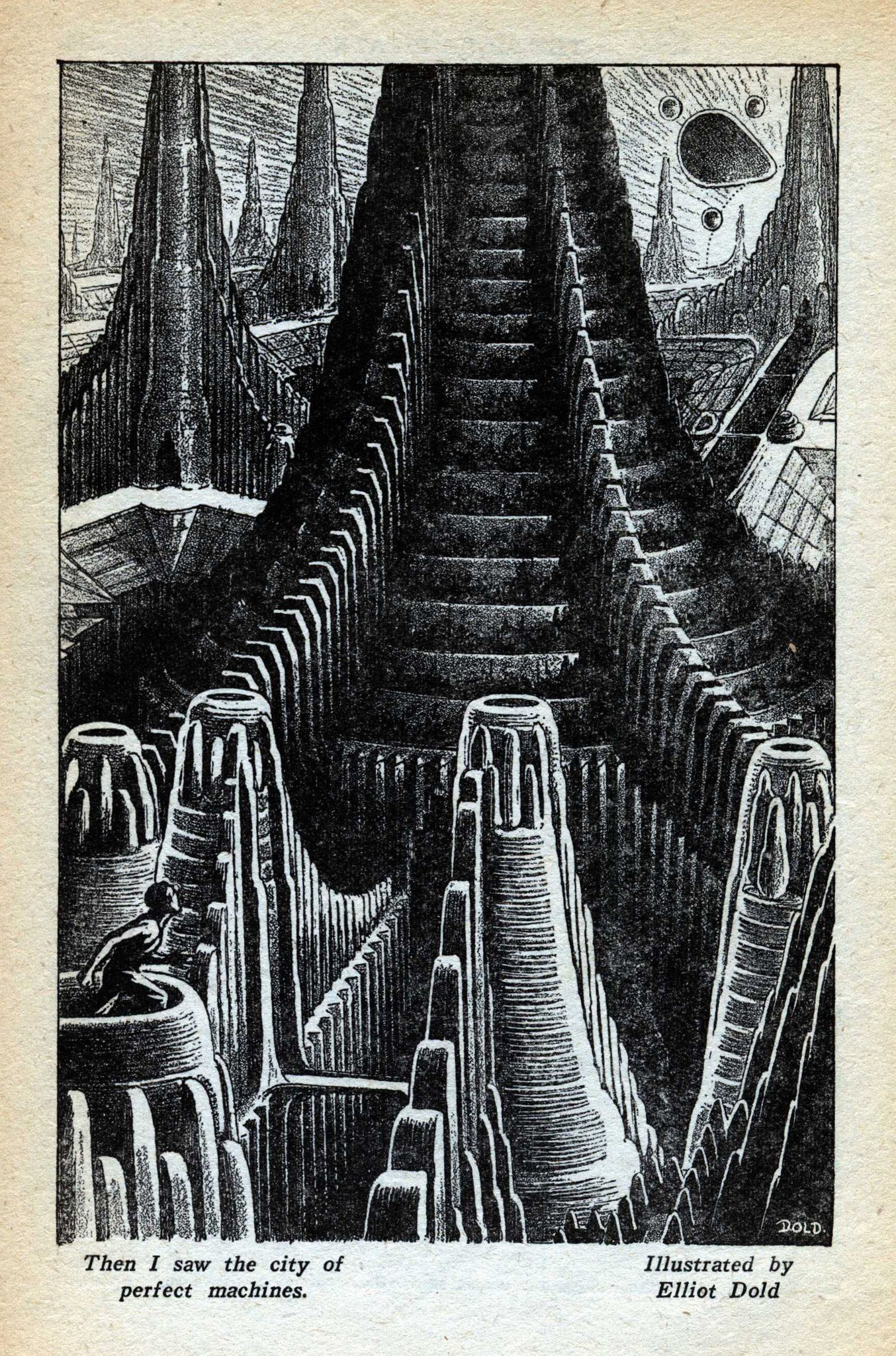

Under Tremaine’s editorship, Astounding Stories pulled itself above its pulp-fiction origins with stories like Jack Williamson’s “Legion of Space” and John W. Campbell’s “Twilight.” The latter inspired the striking illustration above by artist Elliott Dold. “Dold’s work was deeply influenced by Art Deco, which lends its geometric forms to the city of machines in ‘Twilight,’ ” writes the New York Times’ Alec Nevala-Lee, which “inaugurated the modern era of science fiction.”

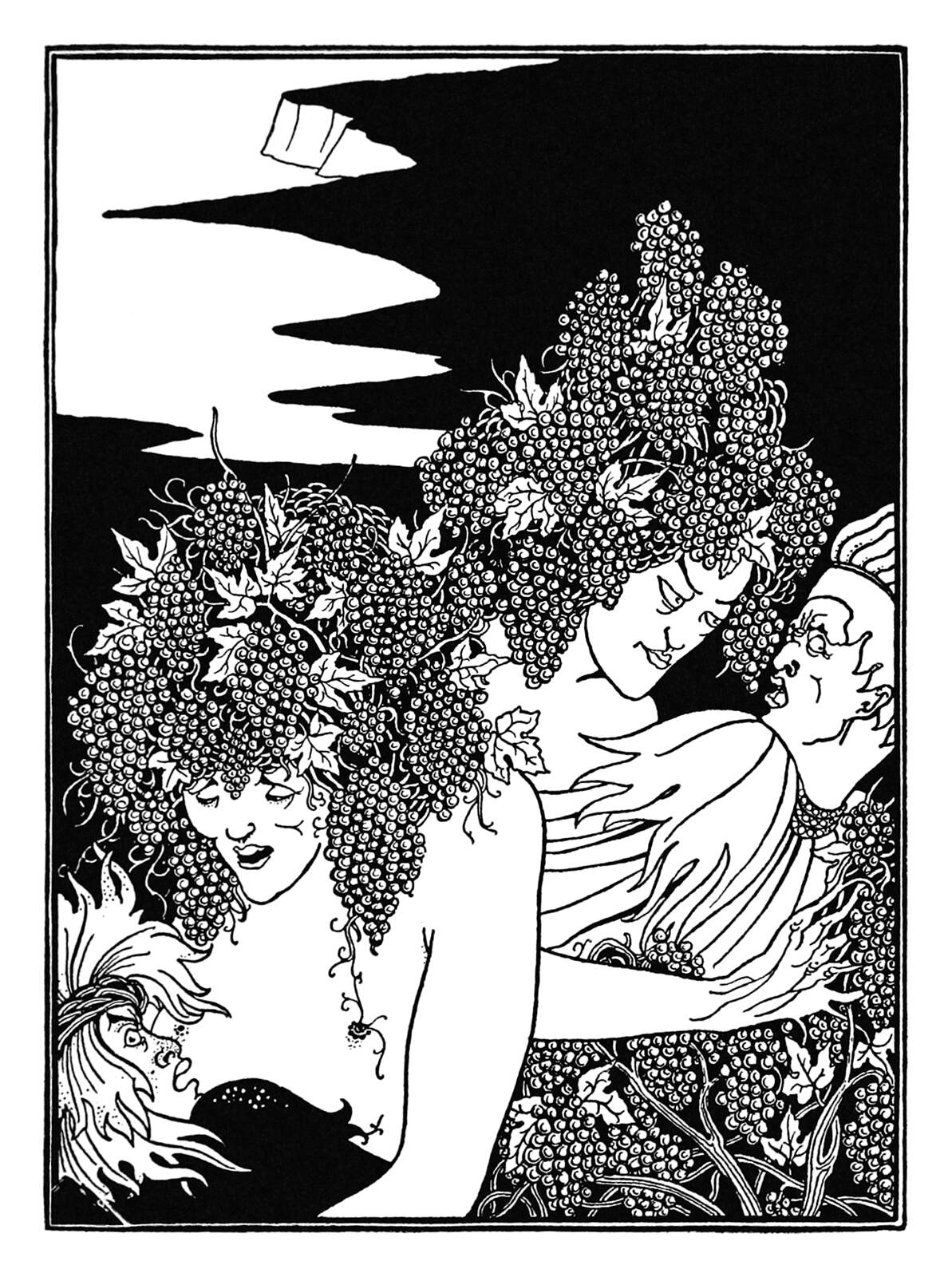

In the case of a golden-age science-fiction magazine like Astounding Stories, Nevala-Lee argues, “its most immediate impact came through its illustrations,” which “may turn out to be the genre’s most lasting contribution to our collective vision of the future.”

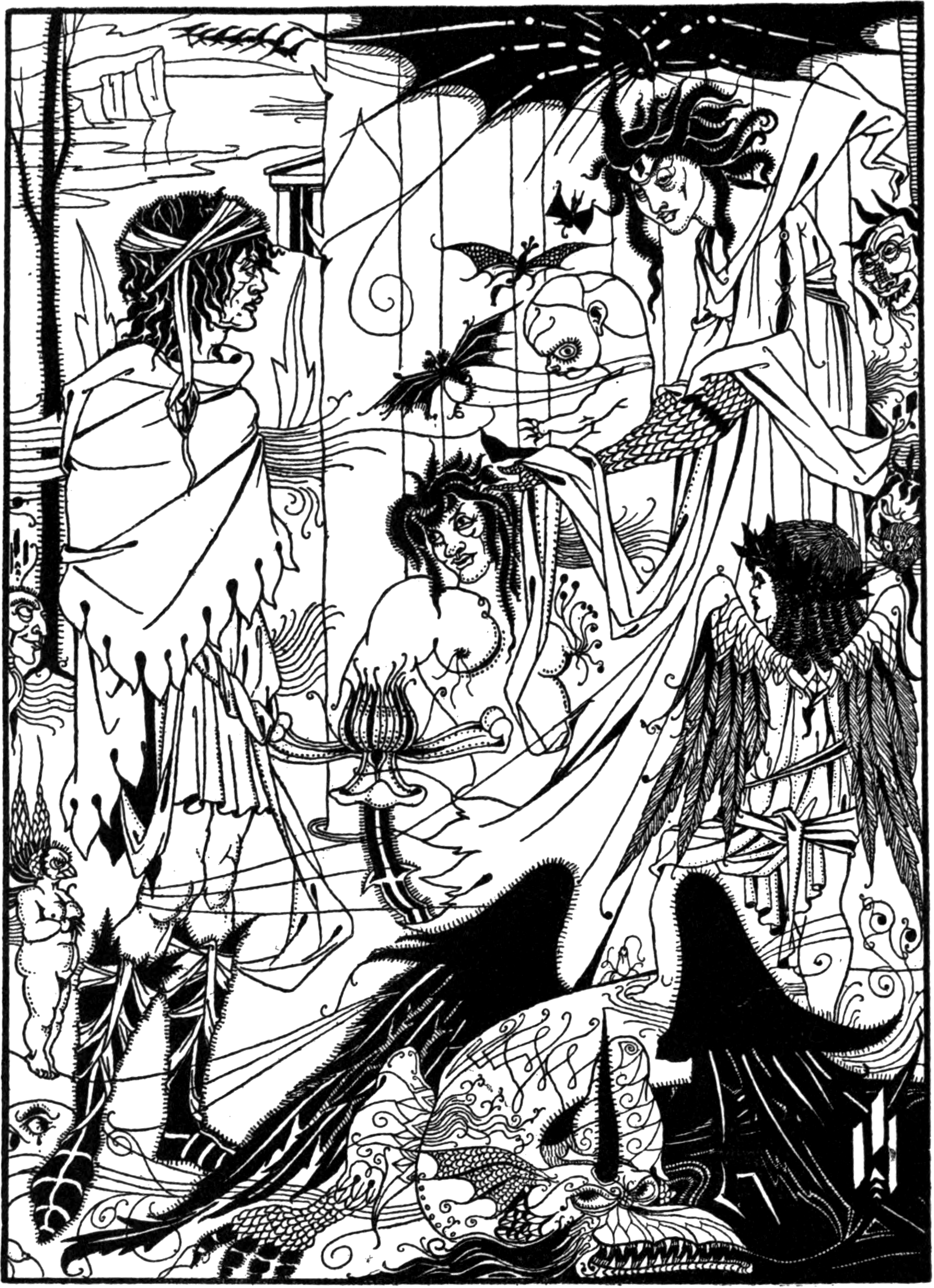

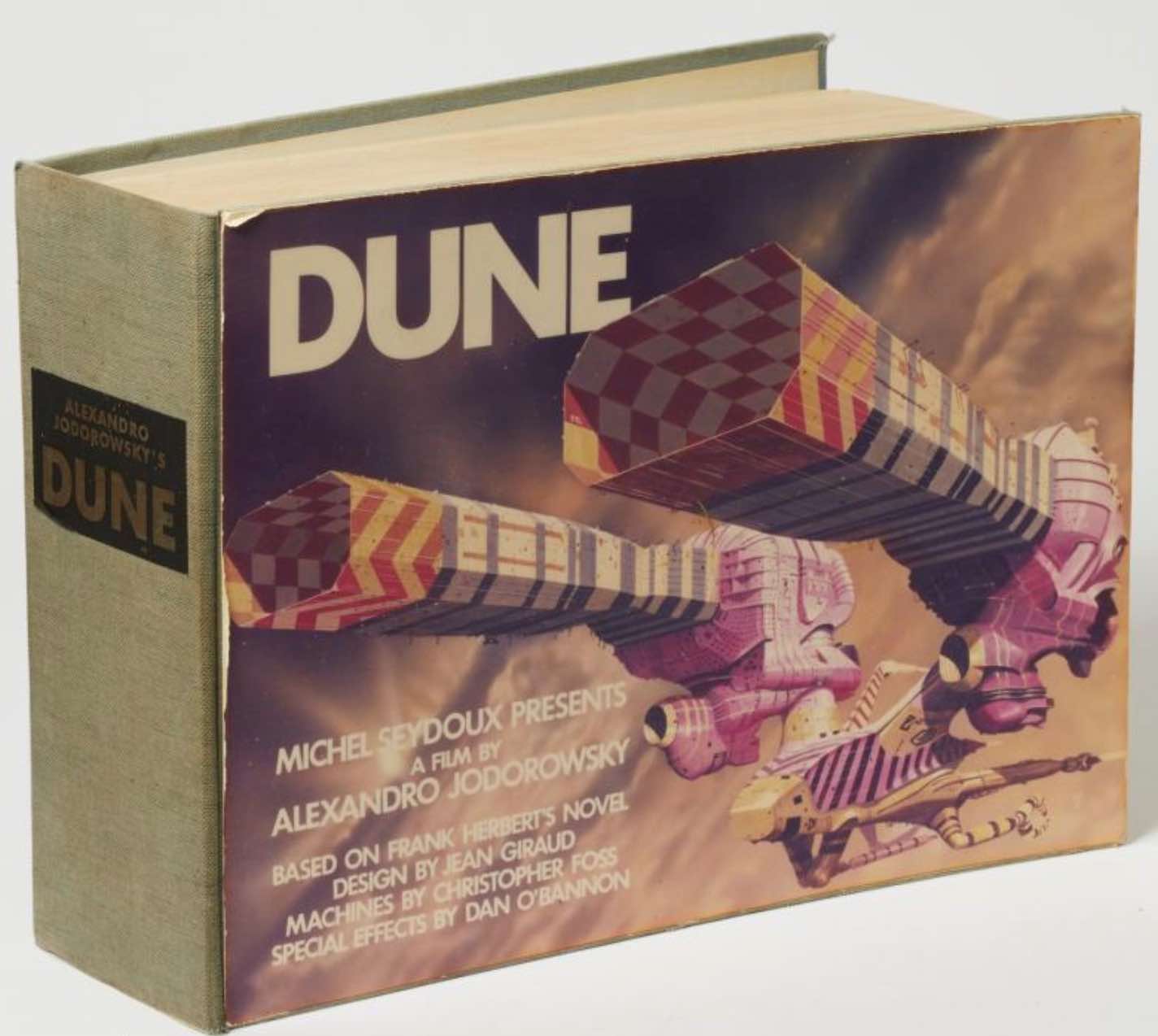

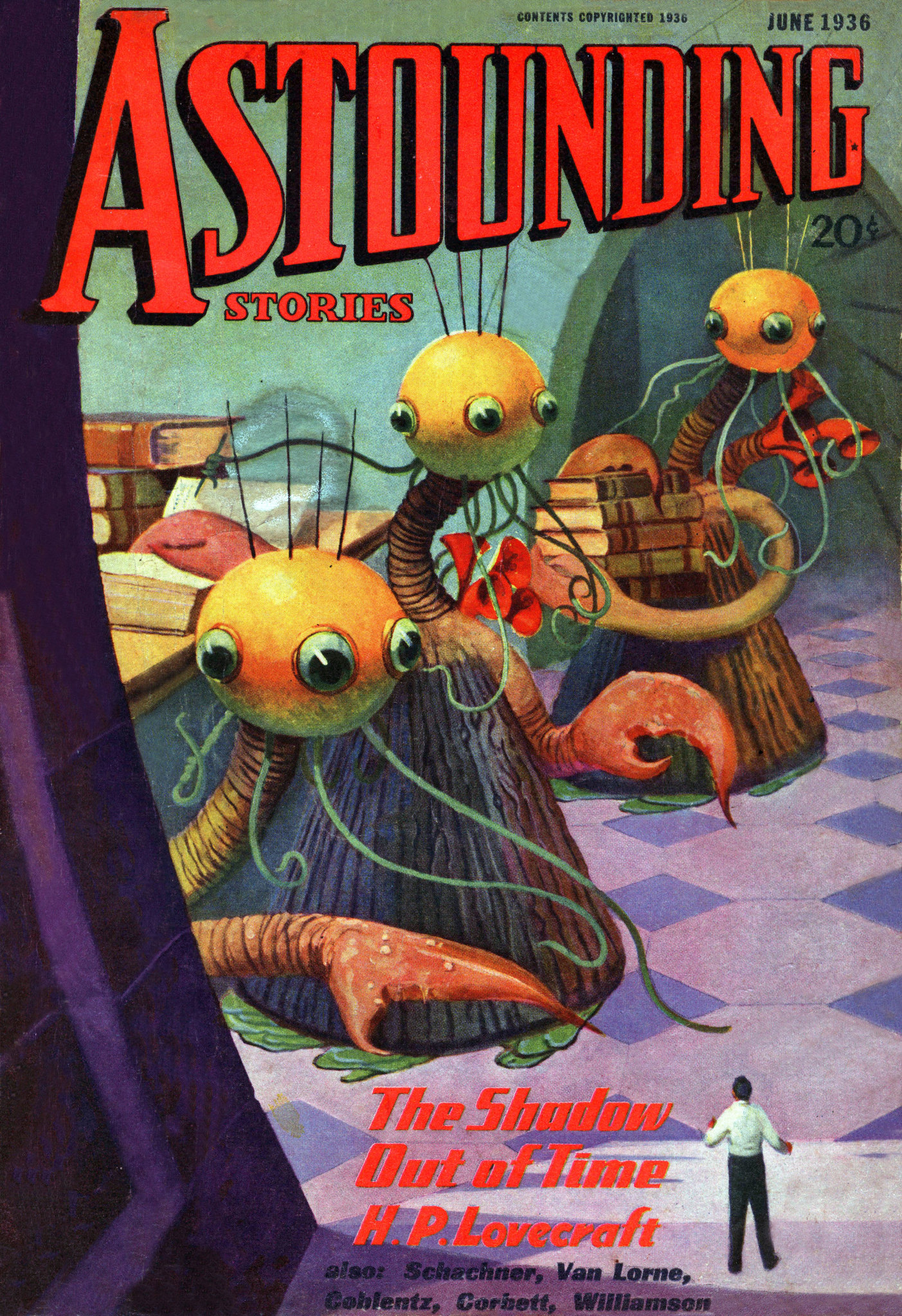

None of the imagery printed inside Astounding Stories was as striking as its covers, full-color productions on which “artists could let their imaginations run wild.” Sometimes they adhered closely to the visual descriptions in a story’s text — perhaps too closely, in the case the June 1936’s issue with H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Shadow Out of Time” — and sometimes they departed from and even competed with the magazine’s actual content. But after Campbell took over as editor in 1937, that content became even stronger: featured writers included Robert Heinlein, A. E. van Vogt, and Isaac Asimov.

Now, here in the once science-fictional-sounding twenty-first century, you can not only behold the covers but read the pages of hundreds of issues of Astounding Stories from the thirties, forties, and fifties online. The earliest volumes are available to download at the University of Pennsylvania’s web site, by way of Project Gutenberg, and there are even more of them free to read at the Internet Archive. Though it may not always have faithfully reflected the material within, Astounding Stories’ cover imagery did represent the publication as a whole. It could be thought-provoking and haunting, but it also delivered no small amount of cheap thrills — and the golden age of science fiction still shows us how thin a line really separates the two.

Related content:

Free: 355 Issues of Galaxy, the Groundbreaking 1950s Science Fiction Magazine

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.