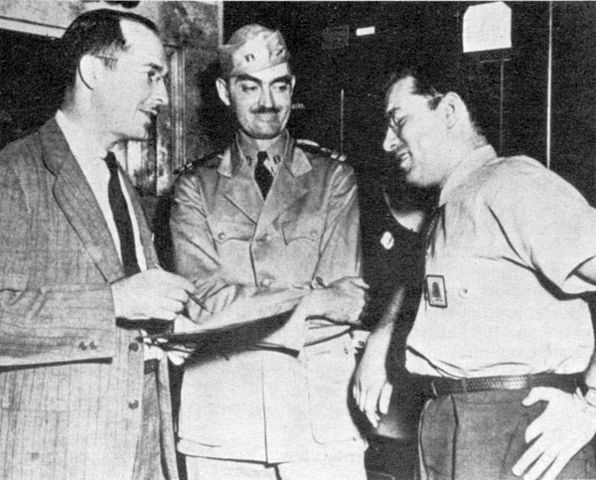

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Two giants of 20th century science fiction: Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov (see them together above, with L. Sprague de Camp in-between). Like every young sci-fi geek, I read them both assiduously, got lost in their dizzying universes that stretched across novels and significant teenage milestones. Even as an awkward kid, I could clearly identify an essential difference in tone between their forecasts of the future. Heinlein, the Navy man forcibly retired from service by tuberculosis, had the darker vision, in which the brute force of mass militarism continued to thrive and heroic men of action carried the day. Asimov, the practicing scientist—whose “Norby” series of kids books might be the cutest introduction to sci-fi ever written by an American—favored a future that, if still quite dangerous, was managed by robots and their creators, the technocrats.

As we can plainly see, we are no less a bellicose species than when these two authors wrote of the future, but Asimov seems to have had it right. The technocrats came out on top; too many battles are fought not by massed battalions but by deadly flying robots making (so we’re told) “surgical” strikes. A few weeks ago, we brought you a series of technocratic predictions of the year 2014 from Asimov, many of them surprisingly accurate. Today, we have a list of predictions from Heinlein, this time of the year 2000, and written in 1949 and published in 1952 in Galaxy magazine. How does his predictive ability stack up against his contemporary? Well, I’d say that 2 (stripped of some exaggeration), 8, and 11 either hit the mark or come pretty damn close. 19 is self-evidently true, and 15 is arguably not terribly far away, though it may not have seemed so in 2000. 4 is painfully ironic. The rest? Eh, not so much. Take a look and try to imagine yourself in Heinlein’s shoes in 1949. Not an easy task? Try to imagine what the world will look like in 2063. Which version of IOS will you be running then?

1. Interplanetary travel is waiting at your front door — C.O.D. It’s yours when you pay for it.

2. Contraception and control of disease is revising relations between the sexes to an extent that will change our entire social and economic structure.

3. The most important military fact of this century is that there is no way to repel an attack from outer space.

4. It is utterly impossible that the United States will start a “preventive war.” We will fight when attacked, either directly or in a territory we have guaranteed to defend.

5. In fifteen years the housing shortage will be solved by a “breakthrough” into new technologies which will make every house now standing as obsolete as privies.

6. We’ll all be getting a little hungry by and by.

7. The cult of the phony in art will disappear. So-called “modern art” will be discussed only by psychiatrists.

8. Freud will be classed as a pre-scientific, intuitive pioneer and psychoanalysis will be replaced by a growing, changing “operational psychology” based on measurement and prediction.

9. Cancer, the common cold, and tooth decay will all be conquered; the revolutionary new problem in medical research will be to accomplish “regeneration,” i.e., to enable a man to grow a new leg, rather than fit him with an artificial limb.

10. By the end of this century mankind will have explored this solar system, and the first ship intended to reach the nearest star will be a‑building.

11. Your personal telephone will be small enough to carry in your handbag. Your house telephone will record messages, answer simple inquiries, and transmit vision.

12. Intelligent life will be found on Mars.

13. A thousand miles an hour at a cent a mile will be commonplace; short hauls will be made in evacuated subways at extreme speed.

14. A major objective of applied physics will be to control gravity.

15. We will not achieve a “World State” in the predictable future. Nevertheless, Communism will vanish from this planet.

16. Increasing mobility will disenfranchise a majority of the population. About 1990 a constitutional amendment will do away with state lines while retaining the semblance.

17. All aircraft will be controlled by a giant radar net run on a continent-wide basis by a multiple electronic “brain.”

18. Fish and yeast will become our principal sources of proteins. Beef will be a luxury; lamb and mutton will disappear.

19. Mankind will not destroy itself, nor will “Civilization” be destroyed.

Here are things we won’t get soon, if ever:

– Travel through time

– Travel faster than the speed of light

– “Radio” transmission of matter.

– Manlike robots with manlike reactions

– Laboratory creation of life

– Real understanding of what “thought” is and how it is related to matter.

– Scientific proof of personal survival after death.

– Nor a permanent end to war.

Curiously, neither Heinlein nor Asimov foresaw that most terribly banal and ubiquitous phenomenon of reality TV, but really, what kind of monster could have imagined such a thing?

via Lists of Note/i09

Related Content:

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964 … And Kind of Nails It

Walter Cronkite Imagines the Home of the 21st Century … Back in 1967

Marshall McLuhan Announces That The World is a Global Village

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness