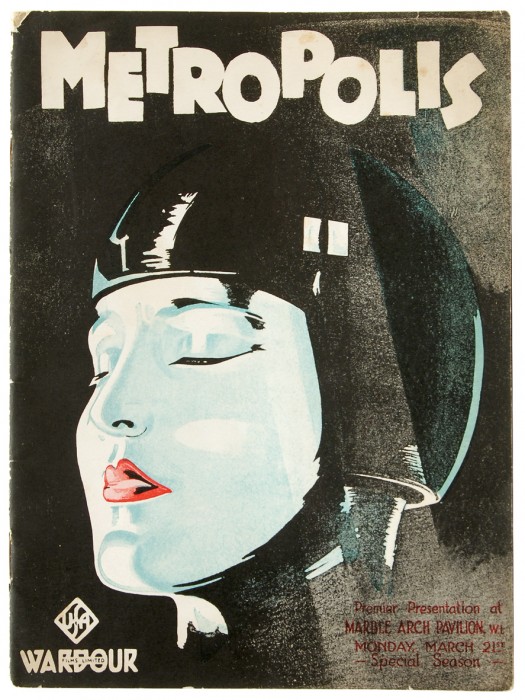

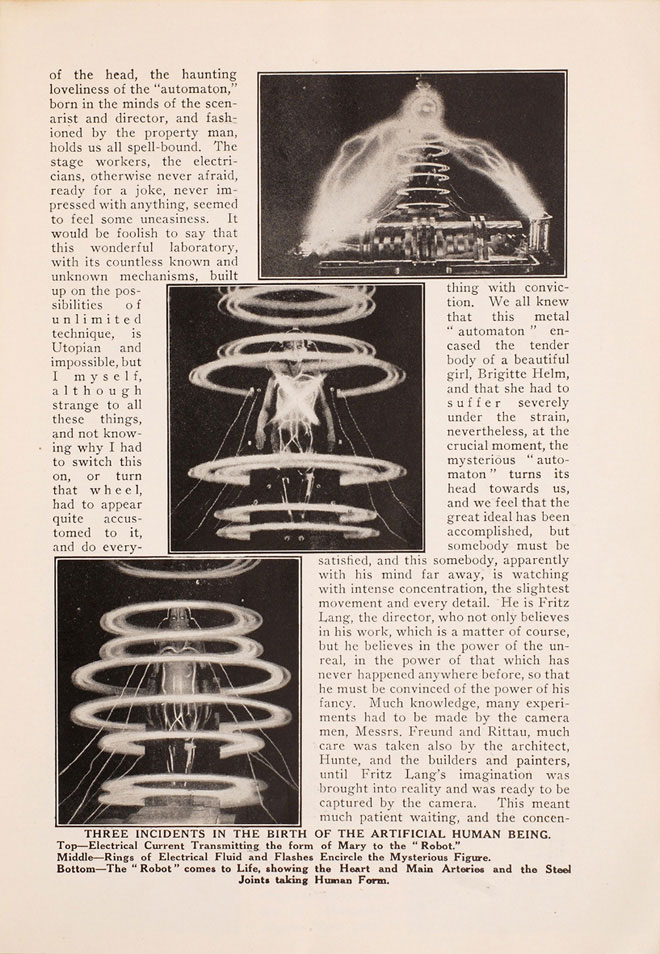

One of the very first feature-length sci-fi films ever made, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis took a daring visual approach for its time, incorporating Bauhaus and Futurist influences in thrillingly designed sets and costumes. Lang’s visual language resonated strongly in later decades. The film’s rather stunning alchemical-electric transference of a woman’s physical traits onto the body of a destructive android—the so-called Maschinenmensch—for example, began a very long trend of female robots in film and television, most of them as dangerous and inscrutable as Lang’s. And yet, for all its many imitators, Metropolis continues to deliver surprises. Here, we bring you a new find: a 32-page program distributed at the film’s 1927 premier in London and recently re-discovered.

In addition to underwriting almost one hundred years of science fiction film and television tropes, Metropolis has had a very long life in other ways: Inspiring an all-star soundtrack produced by Giorgio Moroder in 1984,with Freddie Mercury, Loverboy, and Adam Ant, and a Kraftwerk album. In 2001, a reconstructed version received a screening at the Berlin Film Festival, and UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register added it to their roster. 2002 saw the release of an exceptional Metropolis-inspired anime with the same title. And in 2010 an almost fully restored print of the long-incomplete film—recut from footage found in Argentina in 2008—appeared, adding a little more sophistication and coherence to the simplistic story line.

Even at the film’s initial reception, without any missing footage, critics did not warm to its story. For all its intense visual futurism, it has always seemed like a very quaint, naïve tale, struck through with earnest religiosity and inexplicable archaisms. Contemporary reviewers found its narrative of generational and class conflict unconvincing. H.G. Wells—“something of an authority on science fiction”—pronounced it “the silliest film” full of “every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own.” Few were kinder when it came to the story, and despite its overt religious themes, many saw it as Communist propaganda.

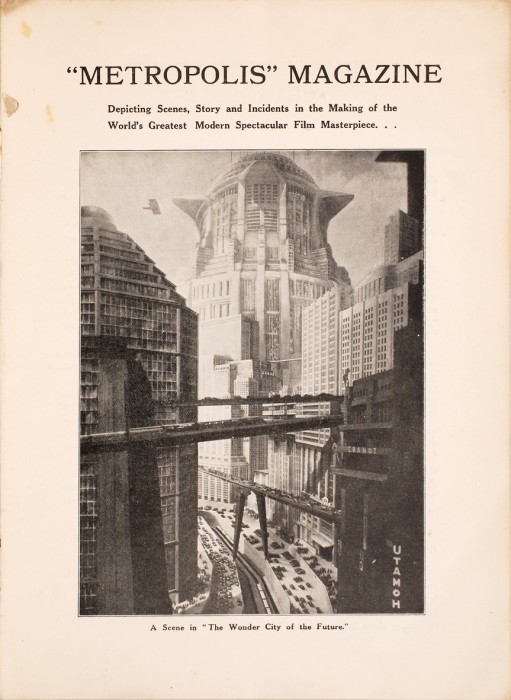

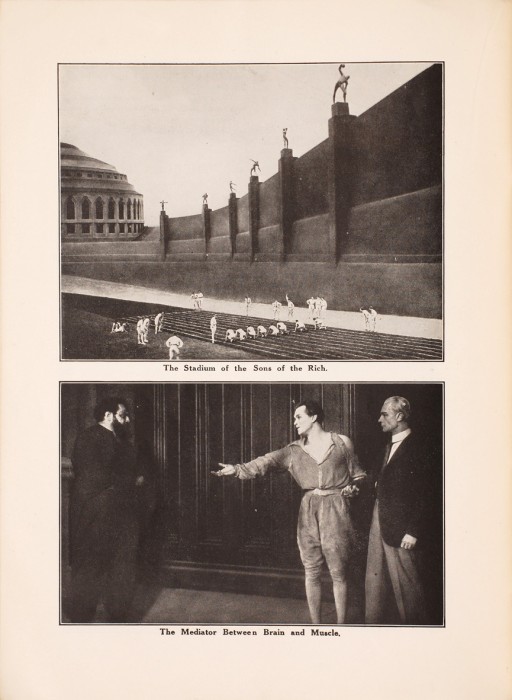

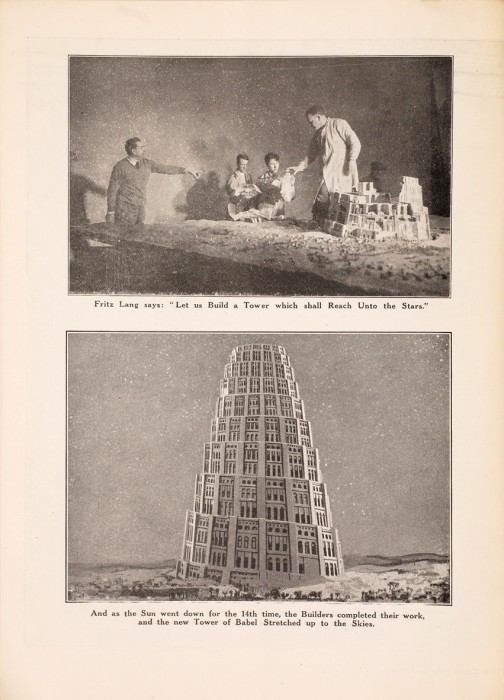

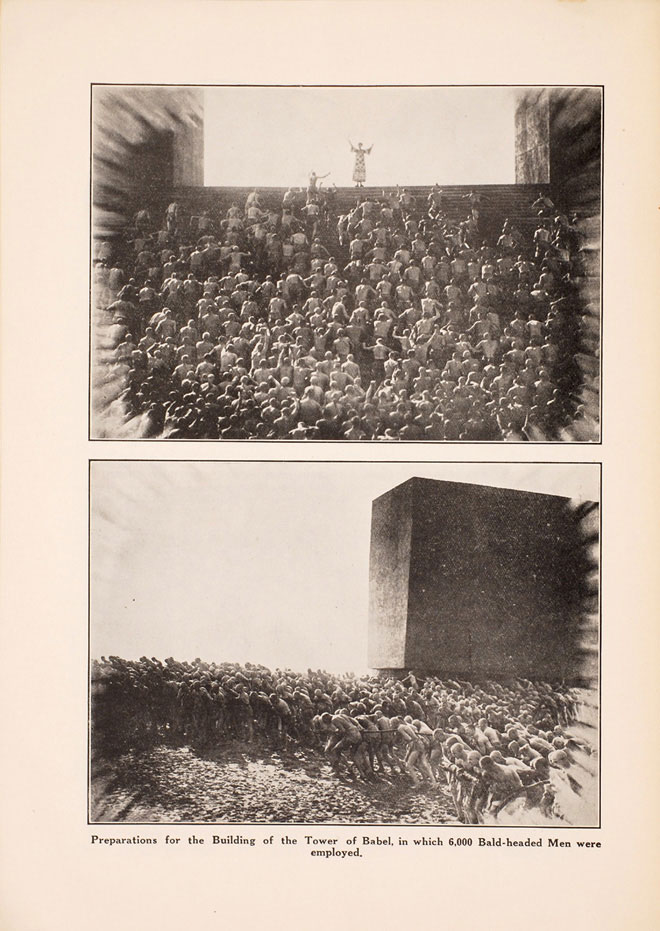

Viewed after subsequent events in 20th century Germany, many of the film’s scenes appear “disturbingly prescient,” writes the Unaffiliated Critic, such as the vision of a huge industrial machine as Moloch, in which “bald, underfed humans are led in chains to a furnace.” Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou—who wrote the novel, then screenplay—were of course commenting on industrialization, labor conditions, and poverty in Weimar Germany. Metropolis’s “clear message of classism,” as io9 writes, comes through most clearly in its arresting imagery, like that horrifying, monstrous furnace and the “looming symbol of wealth in the Tower of Babel.”

The visual effects and spectacular set pieces have worked their magic on almost everyone (Wells excluded) who has seen Metropolis. And they remain, for all its silliness, the primary reason for the movie’s cultural prevalence. Wired calls it “probably the most influential sci-fi movie in history,” remarking that “a single movie poster from the original release sold for $690,000 seven years ago, and is expected to fetch even more at an auction later this year.”

We now have another artifact from the movie’s premiere, this 32-page program, appropriately called “Metropolis” Magazine, that offers a rich feast for audiences, and text at times more interesting than the film’s script. (You can view the program in full here.) One imagines had they possessed backlit smart phones, those early moviegoers might have found themselves struggling not to browse their programs while the film screened. But, of course, Metropolis’s visual excesses would hold their attention as they still do ours. Its scenes of a futuristic city have always enthralled viewers, filmmakers, and (most) critics, such that Roger Ebert could write of “vast futuristic cities” as a staple of some of the best science fiction in his review of the 21st-century animated Metropolis—“visions… goofy and yet at the same time exhilarating.”

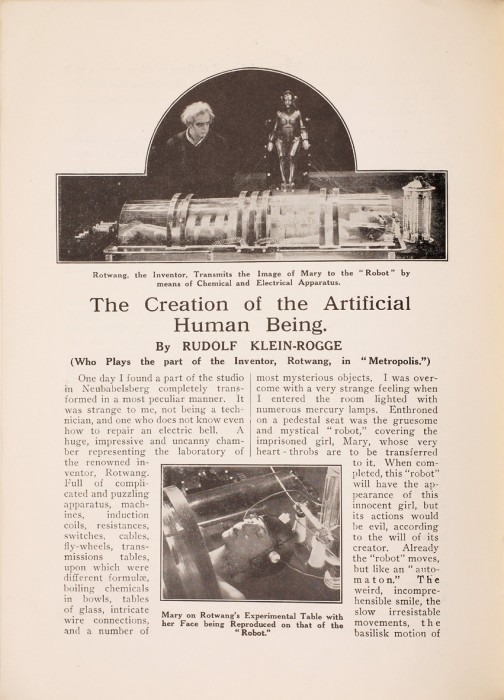

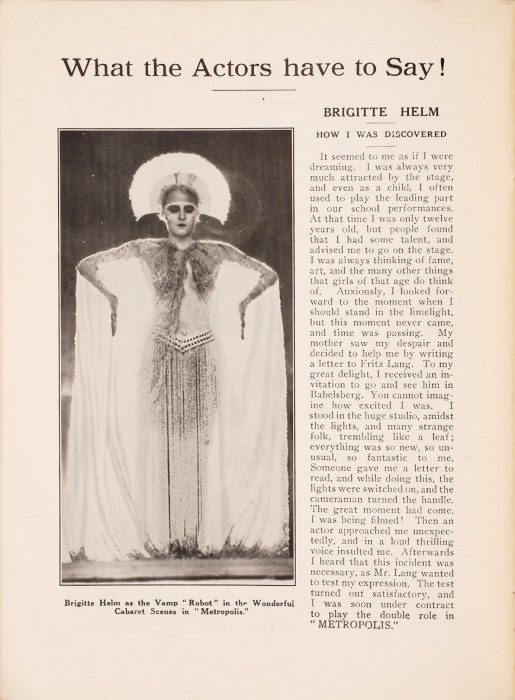

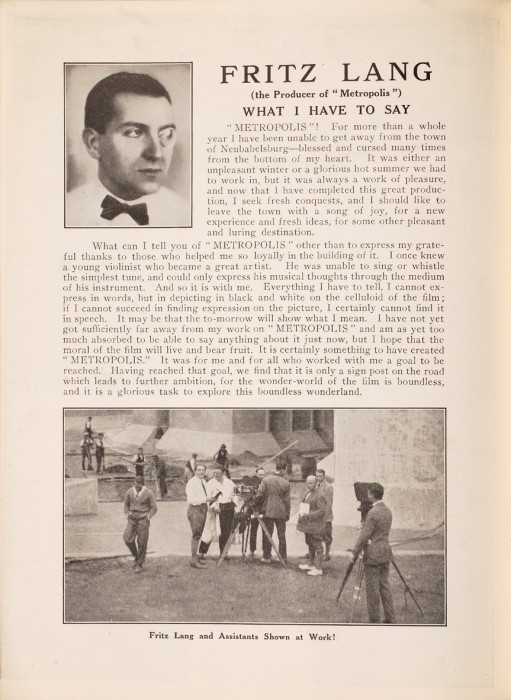

The program really is an astonishing document, a treasure for fans of the film and for scholars. Full of production stills, behind-the-scenes articles and photos, technical minutiae, short columns by the actors, a bio of Thea von Harbau, the “authoress,” excerpts from her novel and screenplay placed side-by-side, and a short article by her. There’s a page called “Figures that Speak” that tallies the production costs and cast and crew numbers (including very crude drawings and numbers of “Negroes” and “Chinese”). Lang himself weighs in, laconically, with a breezy introduction followed by a classic silent-era line: “if I cannot succeed in finding expression on the picture, I certainly cannot find it in speech.” Film history agrees, Lang found his expression “on the picture.”

“Only three surviving copies of this program are known to exist,” writes Wired, and one of them, from which these pages come, has gone on sale at the Peter Harrington rare book shop for 2,750 pounds ($4,244)—which seems rather low, given what an original Metropolis poster went for. But markets are fickle, and whatever its current or future price, ”Metropolis” Magazine is invaluable to cineastes. See all 32 pages of the program at Peter Harrington’s website.

via Wired

Related Content:

Metropolis: Watch a Restored Version of Fritz Lang’s Masterpiece (1927)

Metropolis II: Discover the Amazing, Fritz Lang-Inspired Kinetic Sculpture by Chris Burden

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness