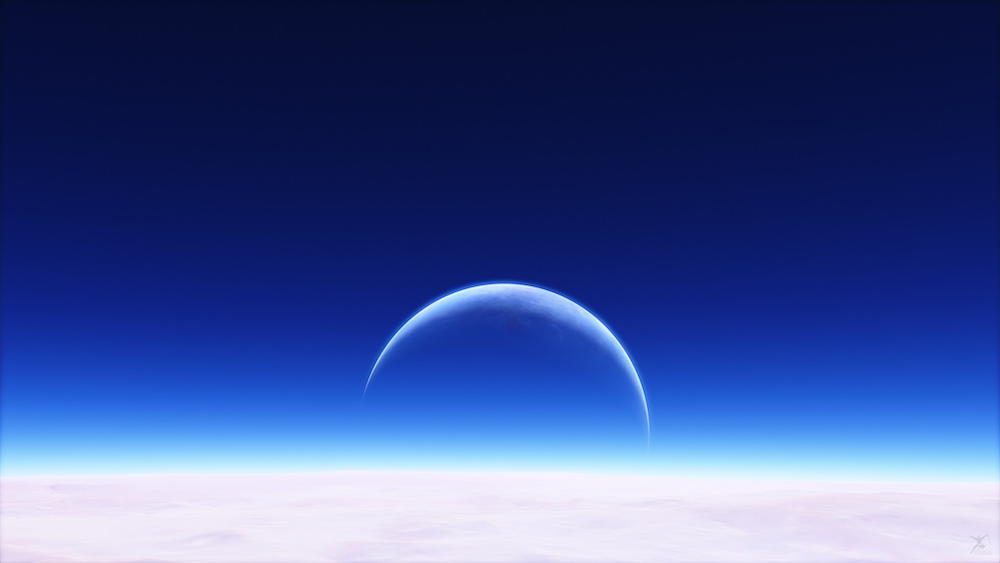

What does space travel look like? Even now, in the 21st century, very, very few of us know first-hand. But we’ve all seen countless images from countless eras purporting to show us what it might look like. As with anything imagined by man, someone had to render a convincing vision of space travel first, and that distinction may well go to 19th-century French illustrator Émile-Antoine Bayard who, perhaps not surprisingly, worked with Jules Verne. Verne’s pioneering and prolific work in science fiction literature has kept him a household name, but Bayard’s may sound more obscure; still, we’ve all seen his artwork, or at least we’ve all seen the drawing of Cosette the orphan he did for Les Misérables.

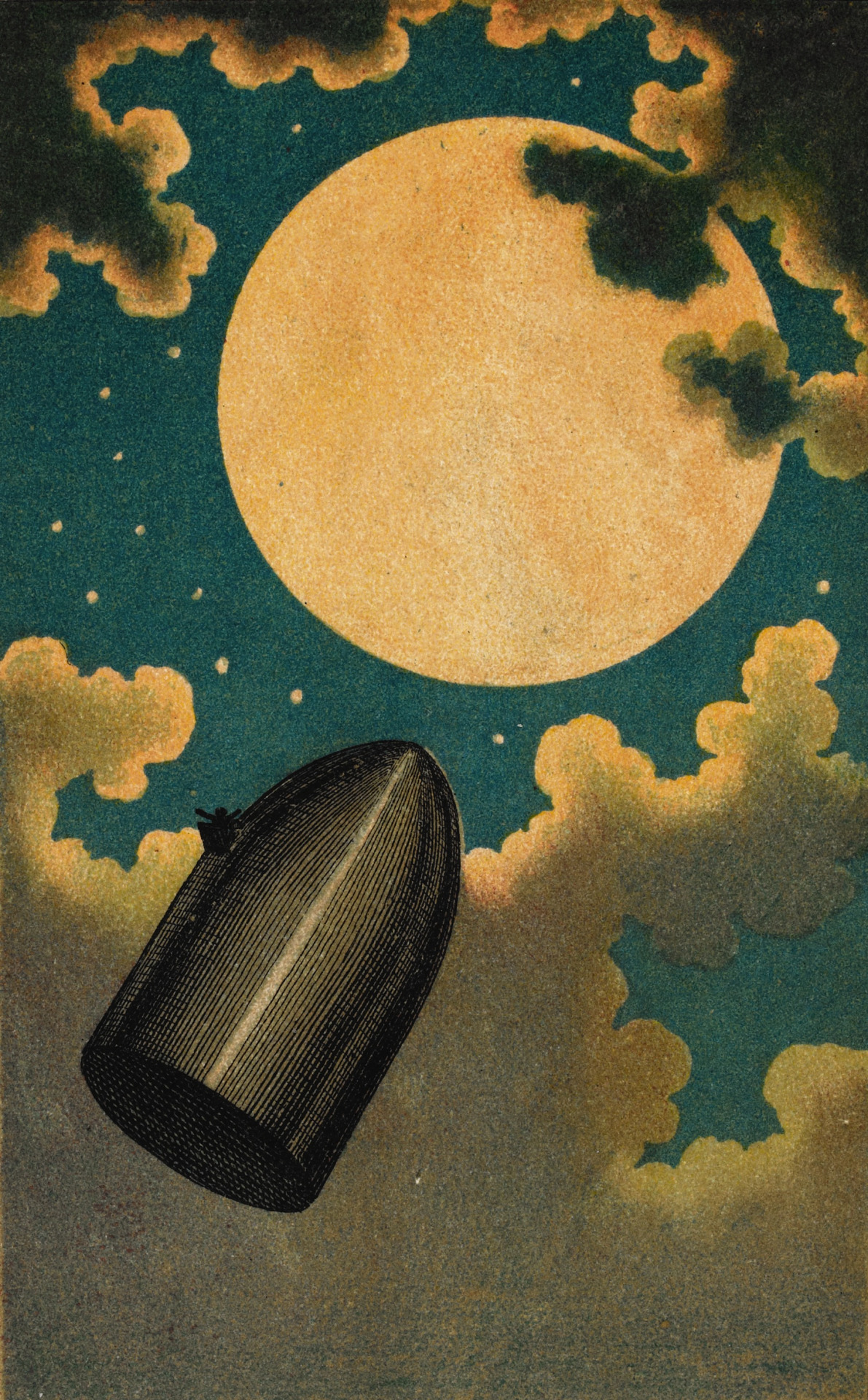

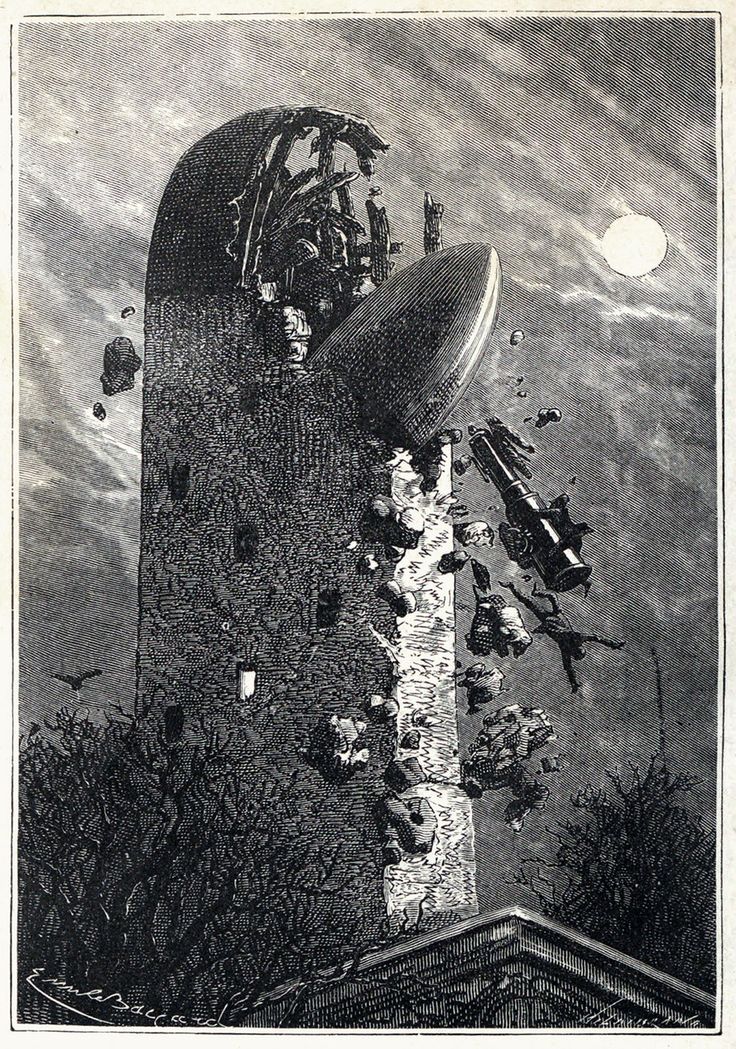

“Readers of Jules Verne’s early science-fiction classic From the Earth to the Moon (De la terre à la lune) — which left the Baltimore Gun Club’s bullet-shaped projectile, along with its three passengers and dog, hurtling through space — had to wait a whole five years before learning the fate of its heroes,” says The Public Domain Review.

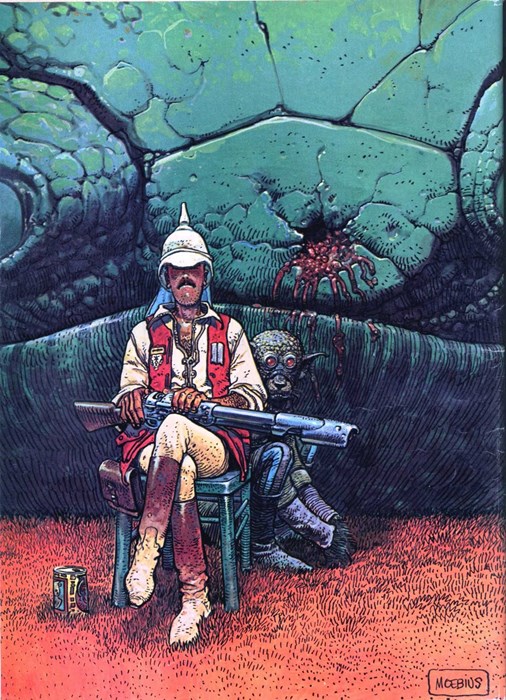

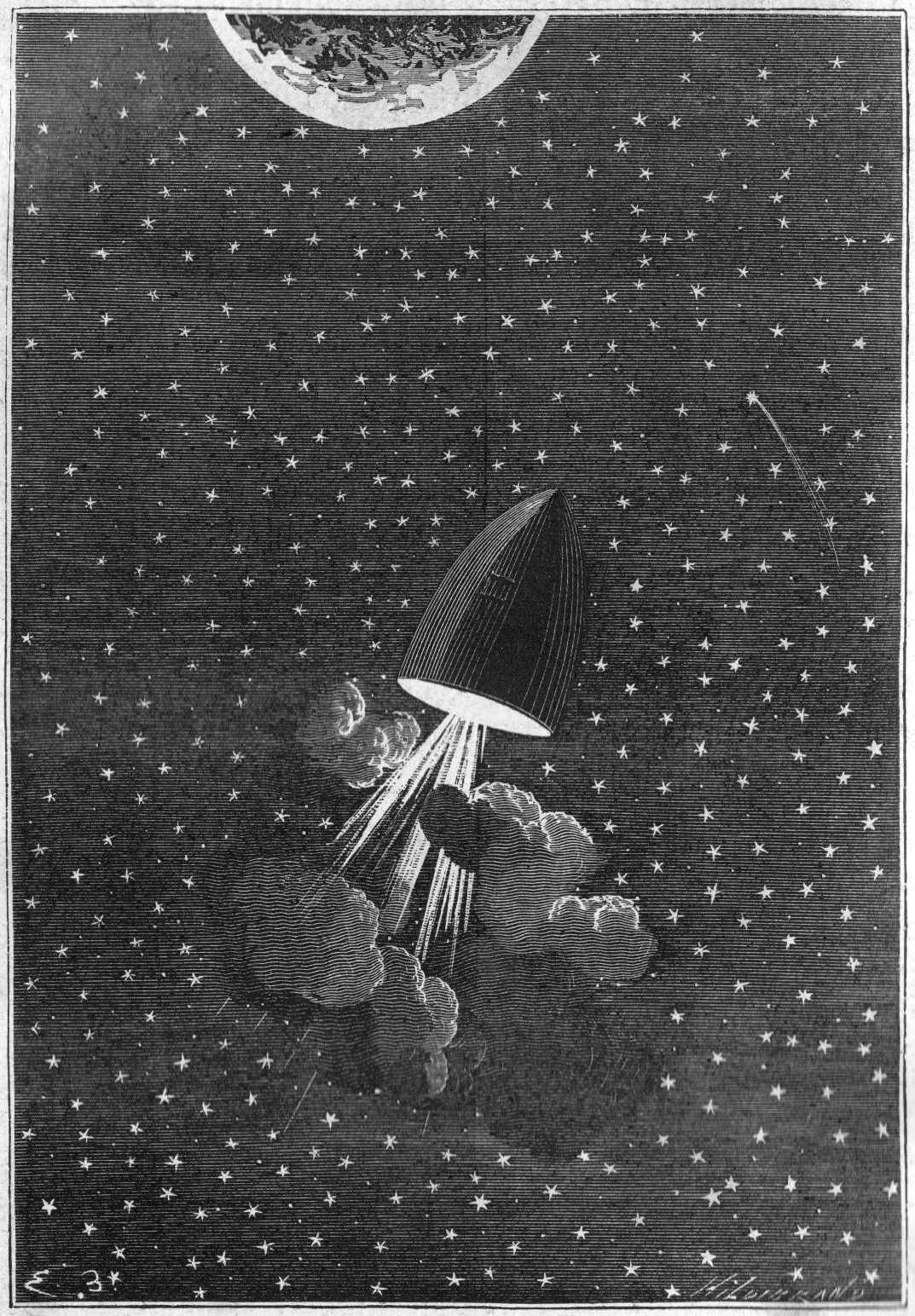

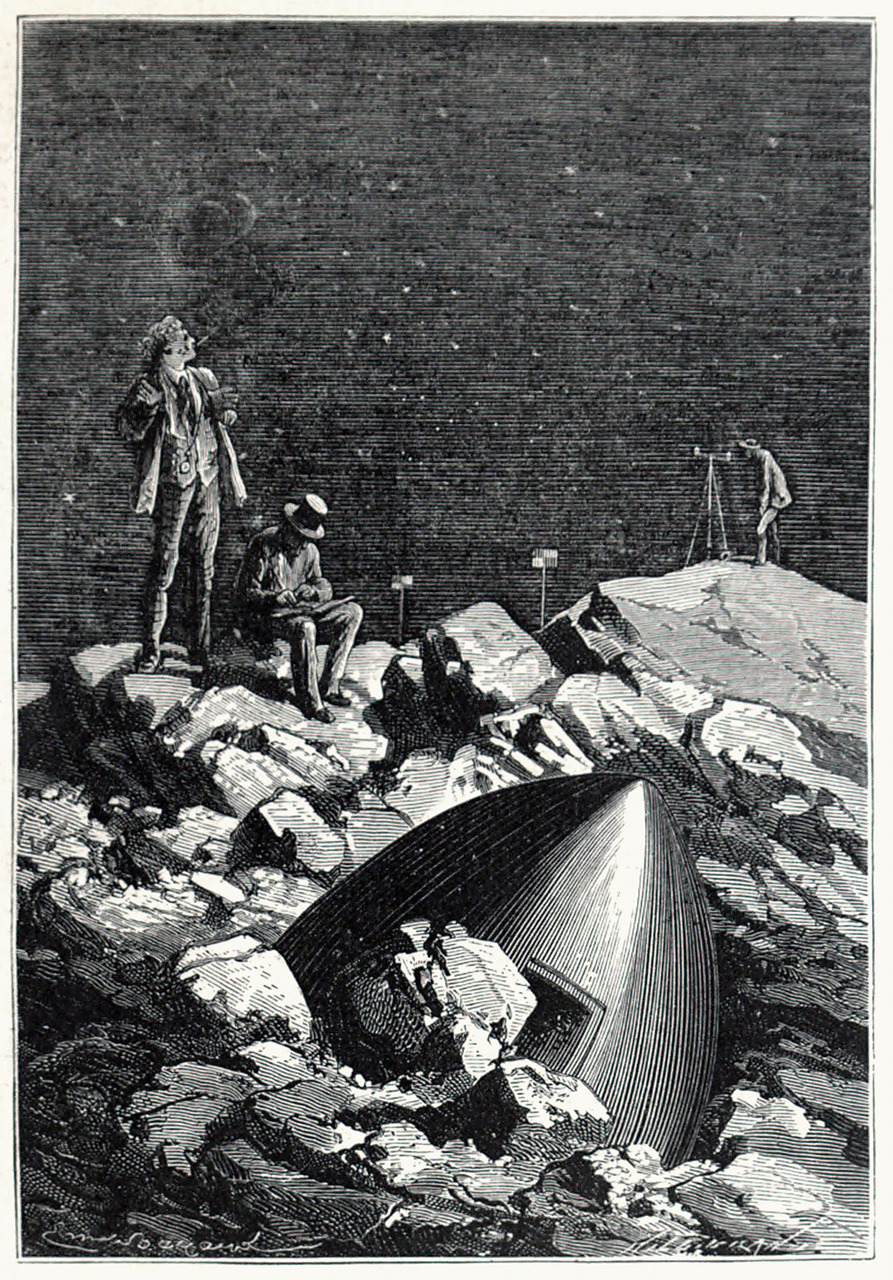

When it appeared, 1870’s Around the Moon (Autour de la Lune) offered not just “a fine continuation of the space adventure” but “a superb series of wood engravings to illustrate the tale” created by Bayard. “There had been imaginary views of other worlds, and even of space flight before this,” writes Ron Miller in Space Art, “but until Verne’s book appeared, these views all had been heavily colored by mysticism rather than science.”

Composed strictly according to the scientific facts known at the time — with a departure here and there in the name of imagination and visual metaphor — the illustrations for A Trip Around the Moon, later published in a single volume with its predecessor as A Trip to the Moon and Around It, stand as the earliest known example of scientific space art. Verne went as far as to commission a lunar map by famed selenographers (literally, scholars of the moom’s surface) Beer and Maedlerm, and just last year the Linda Hall Library named Bayard a “scientist of the day.” As with the uncannily accurate predictions in Verne’s earlier novel Paris in the Twentieth Century, a fair few of the ideas here, especially to do with the mechanics of the rocket’s launch and return to Earth, remain scientifically plausible.

Whatever the innovation of the project’s considerable scientific basis, its artistic impression fired up more than a few other imaginations: both Verne’s words and Bayard’s art, all 44 pieces of which you can view here, served as major inspirations for early filmmaker and “father of special effects” Georges Méliès, for instance, when he made A Trip to the Moon. Disappointed complaints about our persistent lack of moon colonies or even commercial space flight may have long since grown tiresome, but the next time you hear one of us denizens of the 21st century air them, remember the work of Verne and Bayard and think of how deep into history that desire really runs.

Via The Public Domain Review.

Related Content:

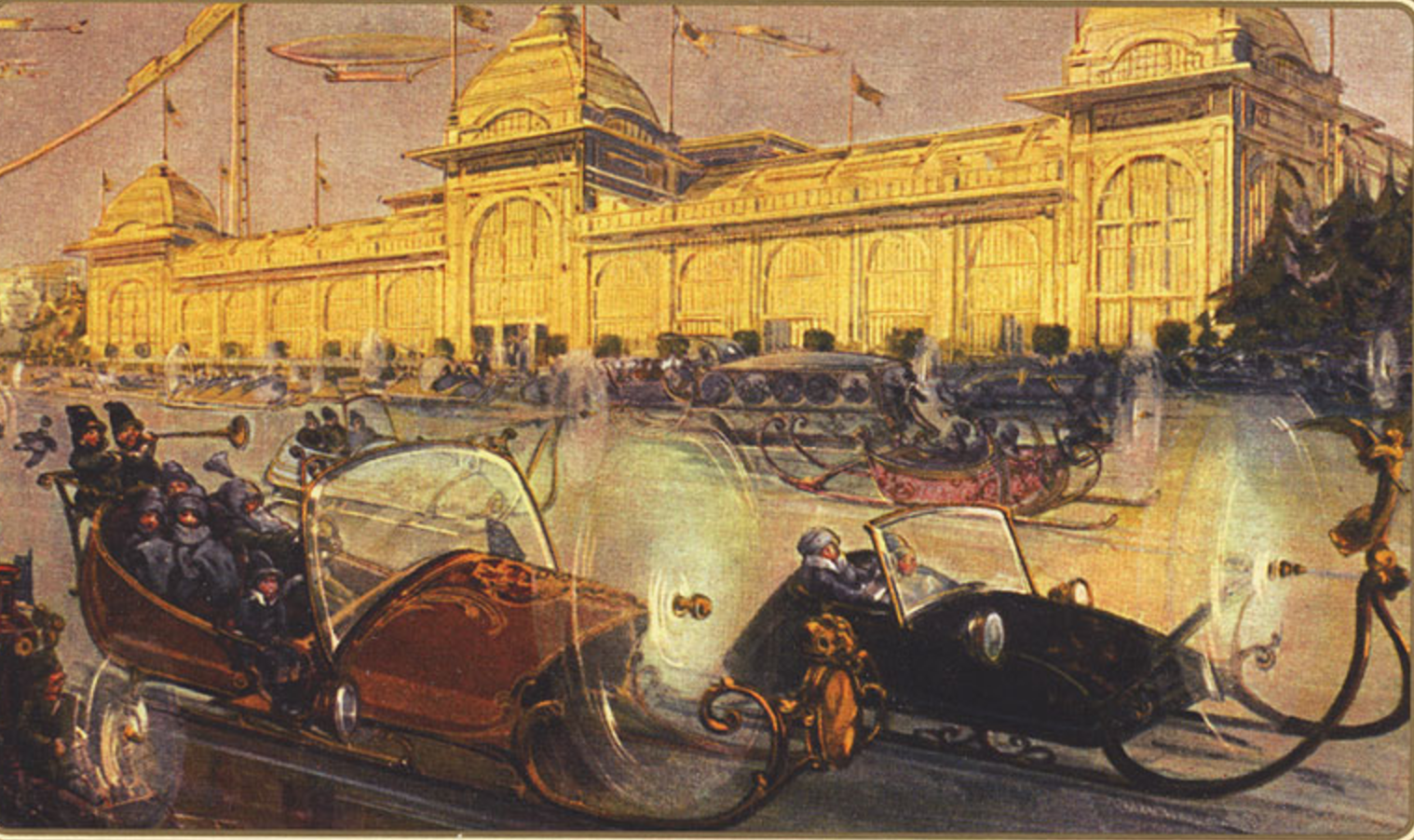

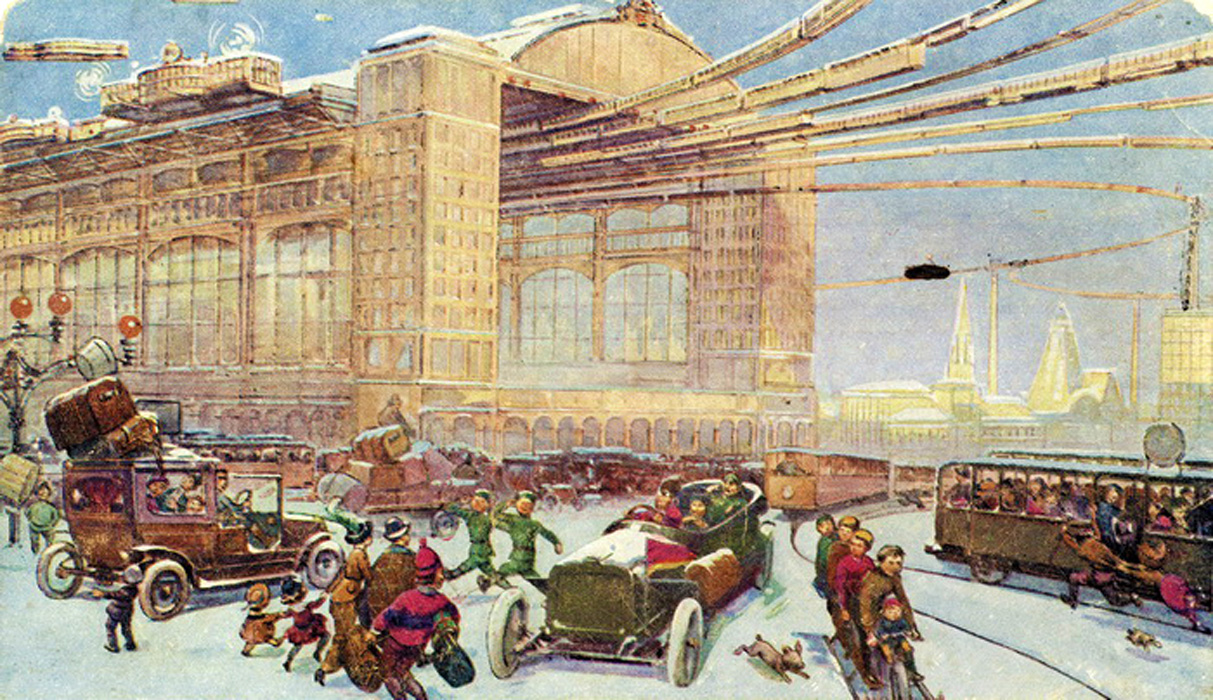

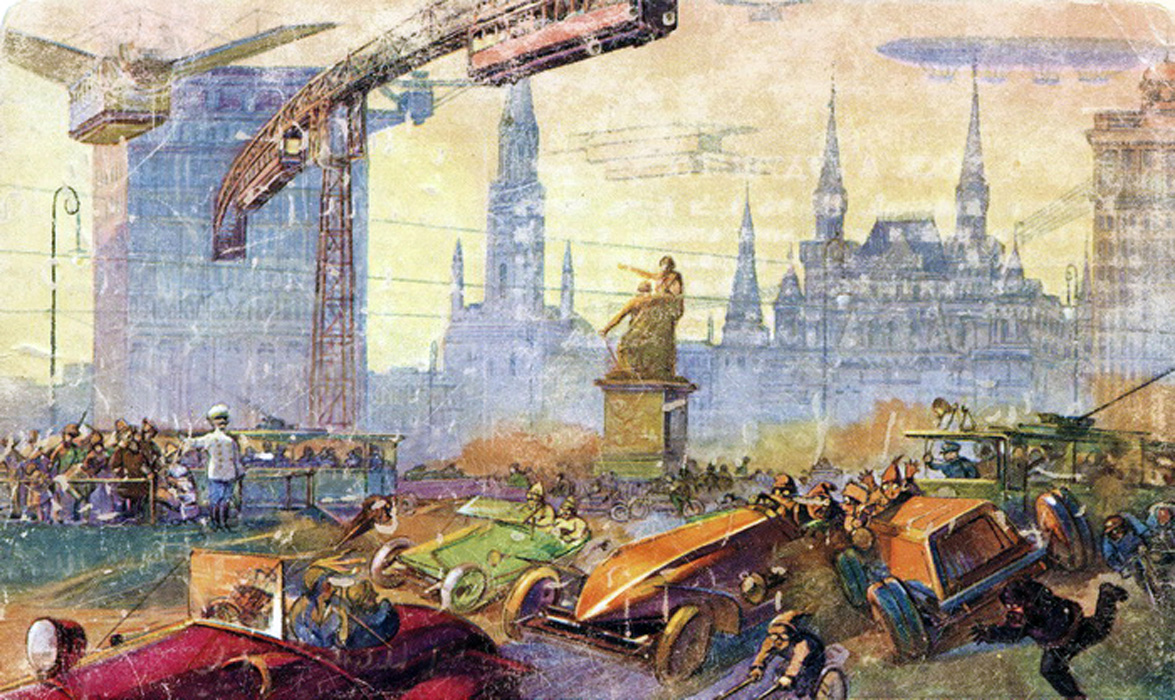

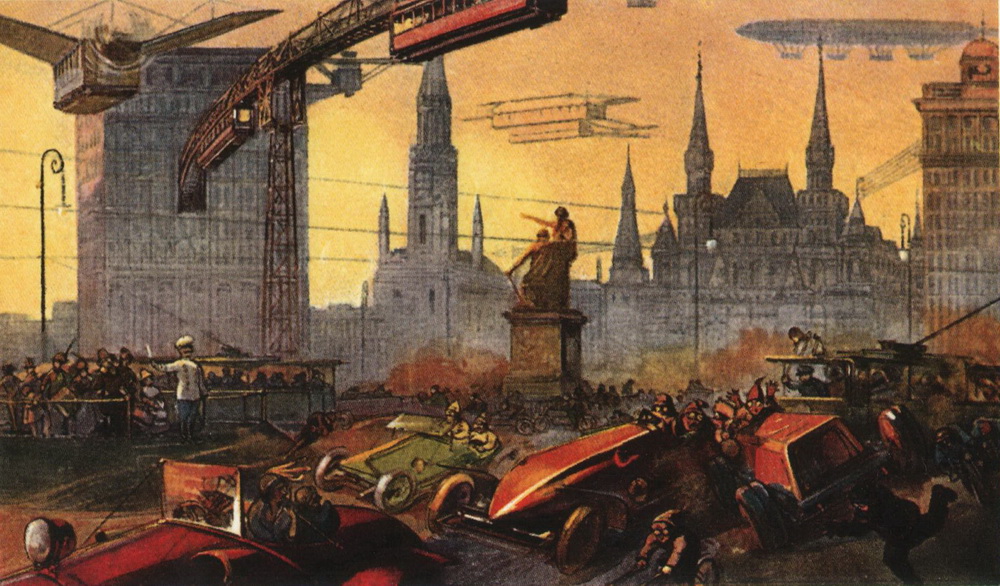

How French Artists in 1899 Envisioned Life in the Year 2000: Drawing the Future

Soviet Artists Envision a Communist Utopia in Outer Space

A Trip to the Moon (and Five Other Free Films) by Georges Méliès, the Father of Special Effects

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.