“I saw God,” Fat states, and Kevin and I and Sherri state, “No, you just saw something like God, exactly like God.” And having spoke, we do not stay to hear the answer, like jesting Pilate, upon his asking, “What is truth?”

–Philip K. Dick, VALIS

In the months of February and March, 1974, Philip K. Dick met God, or something like God, or what he thought was God, at least, in a hallucinatory experience he chronicled in several obsessively dense diaries that recently saw publication as The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick, a work of deeply personal theo-philosophical reflection akin to Carl Jung’s The Red Book. Whatever it was he encountered—Dick was never too dogmatic about it—he ended up referring to it as Zebra, or by the acronym VALIS, Vast Active Living Intelligence System, also the title of a novel detailing the experiences of one very PKD-like character with the improbable name of “Horselover Fat.”

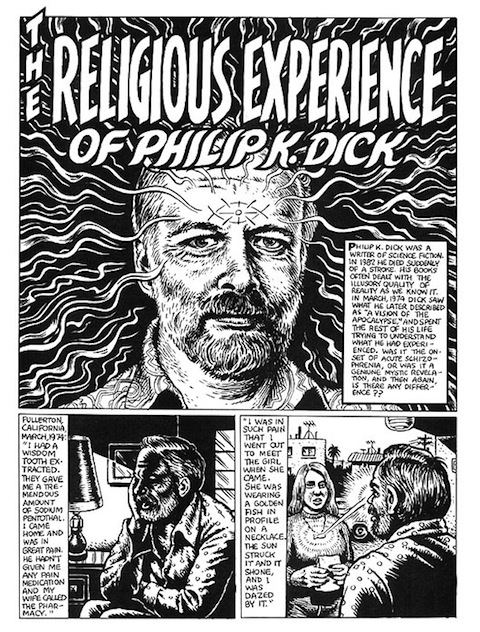

LSD-triggered psychotic break, genuine religious experience, or something else entirely, whatever Dick’s encounter meant, he didn’t let the opportunity to turn it into art slip by him, and neither did outsider cartoonist and PKD fan Robert Crumb. In issue #17 of the underground comix magazine Weirdo, Crumb narrated and illustrated Dick’s meeting with a divine intelligence in the appropriately titled “The Religious Experience of Philip K. Dick.” It was eventually collected in the edition, The Weirdo Years by R. Crumb: 1981-’93. (See the comic in motion in the awkward, amateur video above.) The comic quotes directly from Dick’s telling of the event, which began with a wisdom tooth extraction and was ultimately triggered by a golden Christian fish symbol worn around the neck of a pharmaceutical delivery girl. Most PKD fans will be familiar with the story, whether they treat it as gospel or not, but to see it illustrated with such empathetic intensity by Crumb is truly a treat.

If you only know Crumb as the creator of lascivious Rubenesque women and schlubby, druggy horndog hipsters (like Fritz the Cat), you may be surprised by these emotionally realist illustrations. If you know Crumb’s more serious work, like his take on the book of Genesis, you won’t. In either case, fans of Dick, Crumb, or—most likely—both, won’t want to miss this.

Related Content:

Download 14 Great Sci-Fi Stories by Philip K. Dick as Free Audio Books and Free eBooks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness