For some time now, Slavoj Žižek has been showing up as an author and editor of theology texts alongside orthodox thinkers whose ideas he thoroughly naturalizes and reads through his Marxist lens. Take, for example, an essay titled, after the Catholic G.K. Chesterton, “The ‘Thrilling Romance of Orthodoxy’ ” in the 2005 volume, partly edited by Žižek, Theology and the Political: The New Debate. In Chesterton’s defense of Christian orthodoxy, Žižek sees “the elementary matrix of the Hegelian dialectical process.” While “the pseudo-revolutionary critics of religion” eventually sacrifice their very freedom for “the atheist radical universe, deprived of religious reference… the gray universe of egalitarian terror and tyranny,” the same paradox holds for the fundamentalists. Those “fanatical defenders of religion started with ferociously attacking the contemporary secular culture and ended up forsaking religion itself (losing any meaningful religious experience).”

For Žižek, a middle way between these two extremes emerges, but it is not Chesterton’s way. Through his method of teasing paradox and allegory from the cultural artifacts produced by Western religious and secular ideologies—supplementing dry Marxist analysis with the juicy voyeurism of psychoanalysis—Žižek finds that Christianity subverts the very theology its interpreters espouse. He draws a conclusion that is very Chestertonian in its ironical reversal: “The only way to be an atheist is through Christianity.” This is the argument Žižek makes in his latest film, The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. In the clip above, over footage from Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, Žižek claims:

Christianity is much more atheist than the usual atheism, which can claim there is no God and so on, but nonetheless it retains a certain trust into the Big Other. This Big Other can be called natural necessity, evolution, or whatever. We humans are nonetheless reduced to a position within the harmonious whole of evolution, whatever, but the difficult thing to accept is again that there is no Big Other, no point of reference which guarantees meaning.

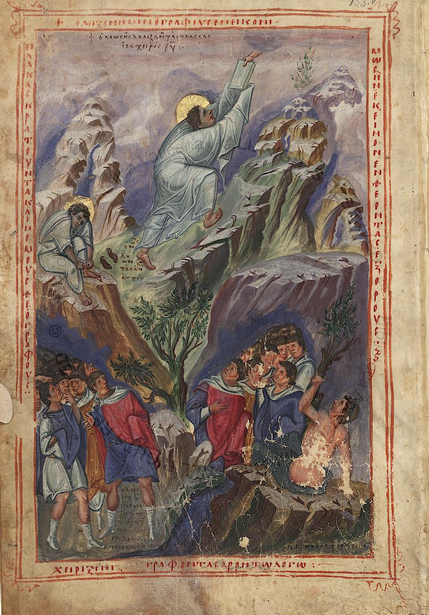

The charge that Christianity is a kind of atheism is not new, of course. It was levied against the early members of the sect by Romans, who also used the word as a term of abuse for Jews and others who did not believe their pagan pantheon. But Žižek means something entirely different. Rather than using atheism as a term of abuse or making a deliberate attempt to shock or inflame, Žižek attempts to show how Christianity differs from Judaism in its rejection of “the big other God” who hides his true desires and intentions, causing immense anxiety among his followers (illustrated, says Žižek, by the book of Job). This is then resolved by Christianity in an act of love, a “resolution of radical anxiety.”

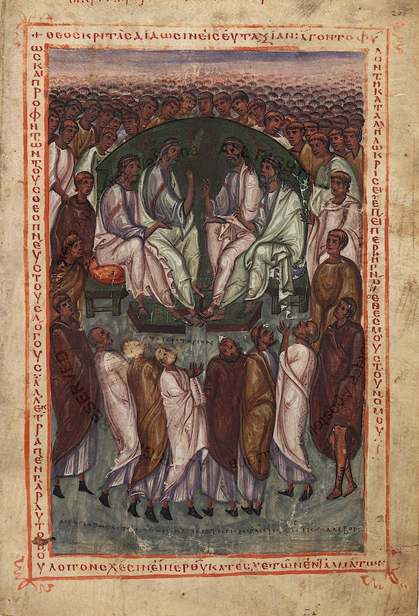

And yet, says Žižek, this act—the crucifixion—does not reinstate the metaphysical certainties of ethical monotheism or populist paganism. “The death of Christ,” says Žižek, “is not any kind of redemption… it’s simply the disintegration of the God which guarantees the meaning of our lives.” It’s a provocative, if not particularly original, argument that many post-Nietzschean theologians have arrived at by other means. Žižek’s reading of Christianity in The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology—alongside his copious writing and lecturing on the subject—constitutes a challenge not only to traditional theistic orthodoxies but also to secular humanism, with its quasi-religious faith in progress and empirical science. Of course, his critique of the vulgar certainties of orthodoxy should also apply to orthodox Marxism, something Žižek’s critics are always quick to point out. Whether or not he’s sufficiently critical of his communist vision of reality, or has anything coherent to say at all, is a point I leave you to debate.

via Biblioklept

Related Content:

Slavoj Žižek’s Pervert’s Guide to Ideology Decodes The Dark Knight and They Live

Noam Chomsky Slams Žižek and Lacan: Empty ‘Posturing’

A Shirtless Slavoj Žižek Explains the Purpose of Philosophy from the Comfort of His Bed

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness