Image via Wikimedia Commons

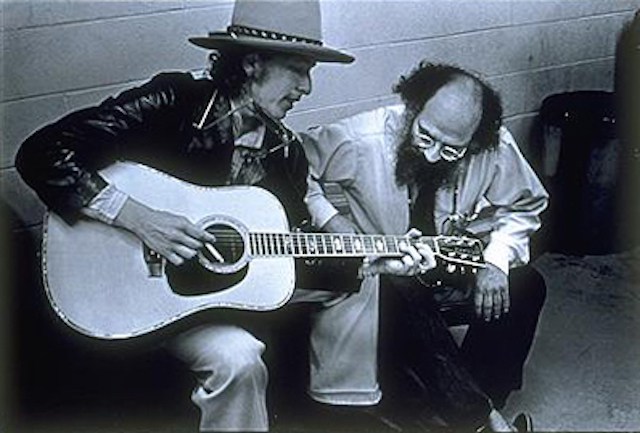

This year’s crazed election got you stressed out? Or just life in general? “It’s never too late,” Allen Ginsberg reminds us, “to meditate.” On Monday, we brought you several versions of Ginsberg’s meditation instructions, which he set to song and recorded with Bob Dylan and disco maven/experimental cellist Arthur Russell, among others. Ginsberg’s “sugar-coated dharma,” as he called it, does a great job of drawing attention to meditation and its benefits, personal and global, but it’s hardly the soothing soundtrack one needs to get in the right posture and frame of mind.

For that, you might try Moby’s 4 hours of ambient music, which he released free to the public through his website last month. Traditionally speaking, no music is necessary, but there’s also no need go the way of Zen monks, or to embrace any form of Buddhism or other religion. Wholly secular forms of mindfulness meditation have been shown to reduce stress, depression, and anxiety, help manage physical pain, improve concentration, and promote a host of other benefits.

Still skeptical? Don’t take my word for it. We’ve pointed you toward the vast amount of scientific research on the subject of mindfulness meditation, much of it conducted by skeptical researchers who came to believe in the benefits after seeing the evidence. If you too have come around to the idea that, yes, you should probably meditate, your next thought may be, but how? Well, in addition to Ginsberg’s witty Vipassana how-to, UCLA has a series of short, guided meditations available on iTunesU. And just above, we have an entire playlist of guided meditations—18 hours in total. It was put together by Spotify, whose free software you can download here.

These include more religiously-oriented kinds of meditations like “Guided Chakra Balancing” and the mystical philosophies of Deepak Chopra, but don’t run off yet if all that’s too woo for you. There are also several hours of very practical, non-religious instruction from teachers like Professor Mark Williams of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, who offers meditations for cognitive therapy. See Williams discuss mindfulness research and meditation as an effective means of managing depression in the video above. (Catch a full mindfulness lecture from Professor Williams and hear another guided meditation from him on Youtube).

You’ll also find a 30-minute guided meditation for sleep, sitar music from Ravi Shankar, and many other guided meditations at various points on the spectrum from the mystical to the wholly practical. Something for everyone here, in other words. Go ahead and give it a try. No matter if you can manage ten minutes or an hour a day, it’s never too late.

Related Content:

Daily Meditation Boosts & Revitalizes the Brain and Reduces Stress, Harvard Study Finds

Allen Ginsberg Teaches You How to Meditate with a Rock Song Featuring Bob Dylan on Bass

Free Guided Meditations From UCLA: Boost Your Awareness & Ease Your Stress

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness