History has remembered John Cage as a composer, but to do justice to his legacy one has to allow that title the widest possible interpretation. He did, of course, compose music: music that strikes the ears of many listeners as quite unconventional even today, more than a quarter-century after his death, but recognizable as music nonetheless. He also composed with silence, an artistic choice that still intrigues people enough to get them taking the plunge into his wider body of work, which also includes compositions of words, many thousands of them written and many hours of them recorded.

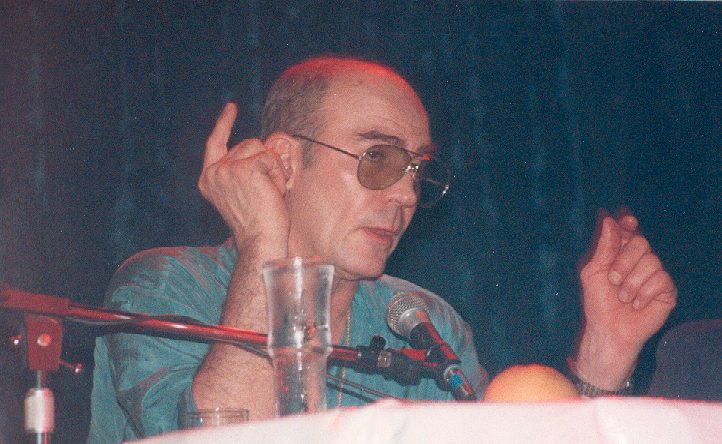

Ubuweb offers an impressive audio archive of Cage’s spoken word, beginning with material from the 1960s and ending with a talk (embedded at the top of the post) he gave at the San Francisco Art Institute in the penultimate year of his life. There he read a 30-minute piece called “One 7” consisting of “brief vocalizations interspersed with long periods of silence” before taking audience questions which “range from inquiries about the process by which Cage composes, his lack of interest in pleasing an audience, his love of mushrooms, Buddhism, chance operations, and whether Cage can stand on his head.”

Turn the Cage clock back 28 years from there and we can hear a spirited 1963 conversation between him and Jonathan Cott, the young music journalist later known for conducting John Lennon’s last interview. “At every turn Cott antagonizes Cage with challenging questions,” says Ubuweb, adding that he marshals “quotes from numerous sources (including Norman Mailer, Michael Steinberg, Igor Stravinsky and others) criticizing Cage and his music.”

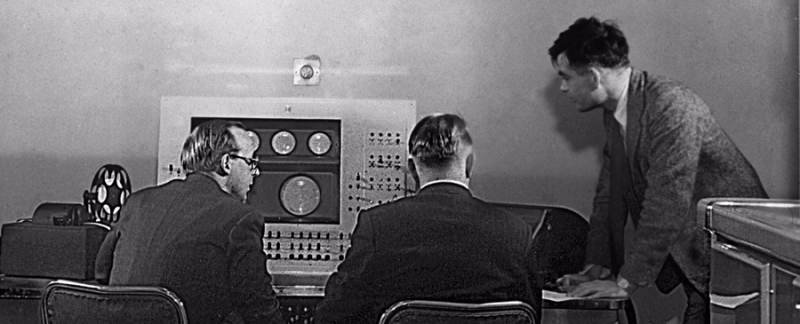

Cage, in characteristic response, “parries Cott’s thrusts with a veritable tai chi practice of music theory.” This contrasts with the mood of Cage’s 1972 interview alongside pianist David Tudor embedded just above, presented in both English and French and featuring references to the work of Henry David Thoreau and Marcel Duchamp.

Cage has more to say about Duchamp, and other artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, in the undated lecture clip from the archives of Pacifica Radio just above. Have a listen through the rest of Ubuweb’s collection and you’ll hear the master of silence speak voluminously, if sometimes cryptically, on such subjects as Zen Buddhism, anarchism, utopia, the work of Buckminster Fuller, and “the role of art and technology in modern society.” The contexts vary, both in the sense of time and place as well as in the sense of the performative expectations placed on Cage himself. But even a sampling of the recordings here suggests that being John Cage, in whatever setting, constituted a productive artistic project all its own.

Related Content:

The Curious Score for John Cage’s “Silent” Zen Composition 4’33”

How to Get Started: John Cage’s Approach to Starting the Difficult Creative Process

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.