There is a well-known scene in Woody Allen’s Take The Money And Run (1969) when Virgil Starkwell (Allen) takes a psychological test to join the Navy, but is thwarted by his lascivious unconscious. The psychological measure that proves to be Starkwell’s undoing—rejected, he turns to a life of crime—is the Rorschach inkblot test, devised almost a century ago by Carl Jung’s compatriot and fellow psychologist, Hermann Rorschach. Although Rorschach would die young, at 37, his namesake remains embedded in our perception of psychology, alongside Freud’s couch and Pavlov’s dog.

Hermann Rorschach’s father was an art teacher, and encouraged his son to express himself. Whether the young Rorschach had innate artistic leanings, or had begun to listen to his father more closely after the death of his mother at age 12, is uncertain. What is known, however, is that Hermann became so fascinated with making pictures out of inkblots—a Swiss game known under the delightful designation of Klecksography—that his schoolmates gave him the nickname of Klecks.

Although he struggled to choose between art and science as a career, Rorschach, on the counsel of eminent German biologist and ardent Darwin supporter Ernst Haeckel, chose medicine, specializing in psychology. Still, he never abandoned art.

Even before the young Rorschach began to study psychology, the medical profession had flirted with imagery association. In 1857, a German doctor named Justinus Kerner published a book of poetry, with each poem inspired by an accompanying inkblot. Alfred Binet, the father of intelligence testing, also tinkered with inkblots at the outset of the 20th century, seeing them as a potential measure of creativity. While stating that Rorschach was familiar with these particular ink blotches reaches no further than educated conjecture, we know that he was familiar with the work of Szyman Hens, an early psychologist who explored his patients’ fantasies using inkblots, as well as Carl Jung’s practice of having his patients engage in word-association.

After noticing that schizophrenic patients associated vastly different things with inkblots than other patients, Rorschach, following some experimentation, created the first version of the inkblot test as a measure of schizophrenia in 1921. The test, however, only came to be used as a form of personality assessment when Samuel Beck and Bruno Klopfer expanded its original scope in the late 1930s. Since then, psychologists have frequently used the various aspects of people’s responses (e.g., inkblot focus area) to make judgment calls about broad personality traits. Ironically, Rorschach himself had been skeptical about the inkblots’ value in assessing personality.

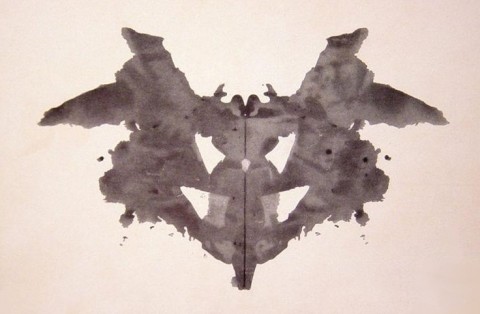

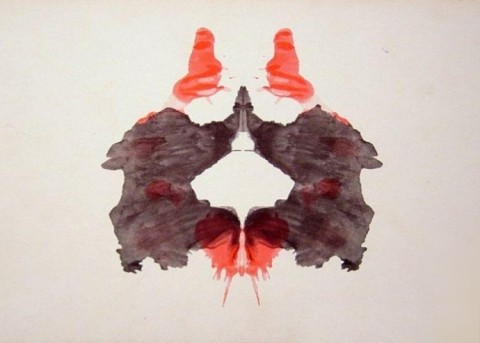

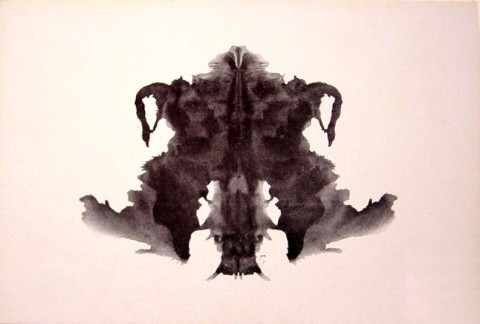

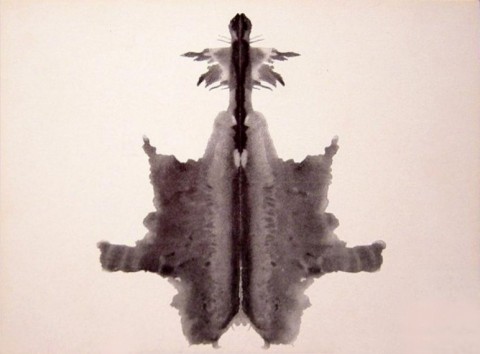

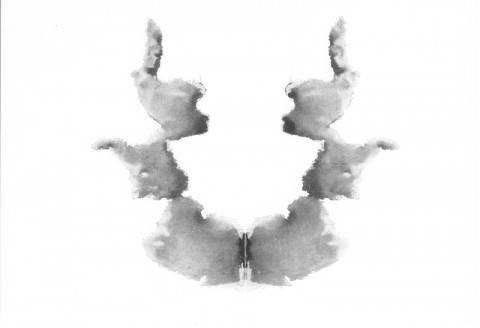

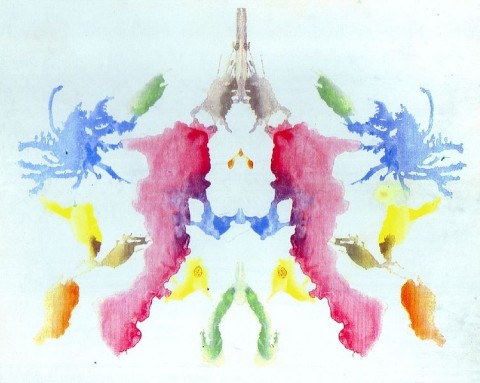

In honor of Rorschach’s birthday (he was born on this day in 1884), we’ve highlighted his original images below, as well as some of the most popular responses. If you see something else in these images, feel free to let us know in the comments section below. The images, we should note, are in the public domain, and otherwise readily viewable on Wikipedia. And, according to Wikimedia Commons, the images are in the public domain.

Image 1: Bat, butterfly, moth

Image 2: Two humans

Image 3: Two humans

Image 4: Animal hide, skin, rug

Image 5: Bat, butterfly, moth

Image 6: Animal hide, skin, rug

Image 7: Human heads or faces

Image 8: Animal; not cat or dog

Image 9: Human

Image 10: Crab, lobster, spider,

Happen to see an elephant and a men’s glee club engaged in unmentionable acts? Don’t fret—you’ve likely projected nothing intelligible. The test has long been out of date, and is deemed neither reliable nor valid in the vast majority of cases (although an updated version exists, it suffers from similar methodological flaws). Virgil Starkwell, it seems, would have made a fine Navy officer.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture writer. Follow him at@iliablinderman