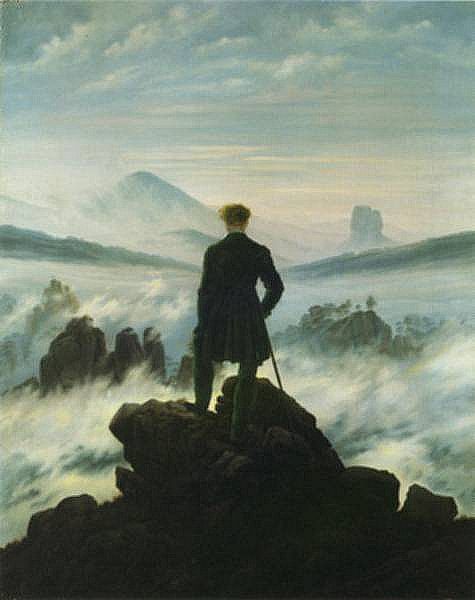

Of all the philosophical concepts Immanuel Kant is known for, the one I’ve had to struggle the least to grasp is his description of the sublime, a state in which we are overawed by the scale of some great work of man or nature. It’s an experience, in typical Kantian fashion, that he explains as being not about the thing itself, but rather the idea of the thing. Yet the concept of the sublime isn’t his. Philosophers from the Greek teacher Longinus in the 1st century to Edmund Burke and other English Enlightenment thinkers in Kant’s own 18th century have had their take on it. For the classical writers, the sublime was rhetorical, for the Brits, it was empirical. But above all, the sublime is peak aesthetics—a supra-rational experience of art or nature one cannot get one’s head around. To be so fully absorbed, so stricken with awe, wonder, and, yes, even fear—all of these philosophers believed in some fashion—is to have an experience critical to transcending our limitations.

We may not, in either common speech or academic philosophy, talk much about the sublime these days, but whatever we call the feeling of being absorbed in art, music, or nature, it turns out to have physical benefits as well as mental and emotional. “There seems to be something about awe,” says professor of psychology Dacher Keltner. “It seems to have pronounced impact on markers related to inflammation.”

In other words, immersing yourself in art or nature is good for the joints, and it could possibly preempt various diseases triggered by inflammation. Keltner and his fellow researchers at UC Berkeley conducted a study which found that “awe, wonder and beauty promote [lower and overall] healthier levels of cytokines”—proteins that “signal the immune system to work harder.” He goes on to say that “the things we do to experience these emotions—a walk in nature, losing oneself in music, beholding art—has [sic] a direct influence upon health and life expectancy.”

Never mind that Kant and Burke thought of the sublime and the beautiful as two very different things. Whether we become totally overwhelmed by, or just find deep appreciation in an aesthetic experience, the emotions produced “might be just as salubrious as hitting the gym,” writes Hyperallergic. That may seem a crude way of thinking about the spiritual and emotional grandeur of the sublime, but it brings our physical being into the discussion in ways many philosophers have neglected. Granted, the researchers themselves admit the causal link is uncertain: it might be better health that leads to more experiences of awe, and not the other way around. But certainly no harm—and a great deal of good—can come from conducting the experiment on yourself. Read an abstract (or purchase a copy) of the Berkeley team’s article here, and learn more about their work with the University’s Greater Good Science Center, which aims to “sponsor groundbreaking scientific research into social and emotional well-being.”

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

This Is Your Brain on Jane Austen: The Neuroscience of Reading Great Literature

Free Guided Meditations From UCLA: Boost Your Awareness & Ease Your Stress

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness