For decades following World War II, the world was left wondering how the atrocities of the Holocaust could have been perpetrated in the midst of—and, most horrifically, by—a modern and civilized society. How did people come to engage in a willing and systematic extermination of their neighbors? Psychologists, whose field had grown into a grudgingly respected science by the midpoint of the 20th century, were eager to tackle the question.

In 1961, Yale University’s Stanley Milgram began a series of infamous obedience experiments. While Adolf Eichmann’s trial was underway in Jerusalem (resulting in Hannah Arendt’s five-piece reportage, which became one of The New Yorker magazine’s most dramatic and controversial article series), Milgram began to suspect that human nature was more straightforward than earlier theorists had imagined; he wondered, as he later wrote, “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?”

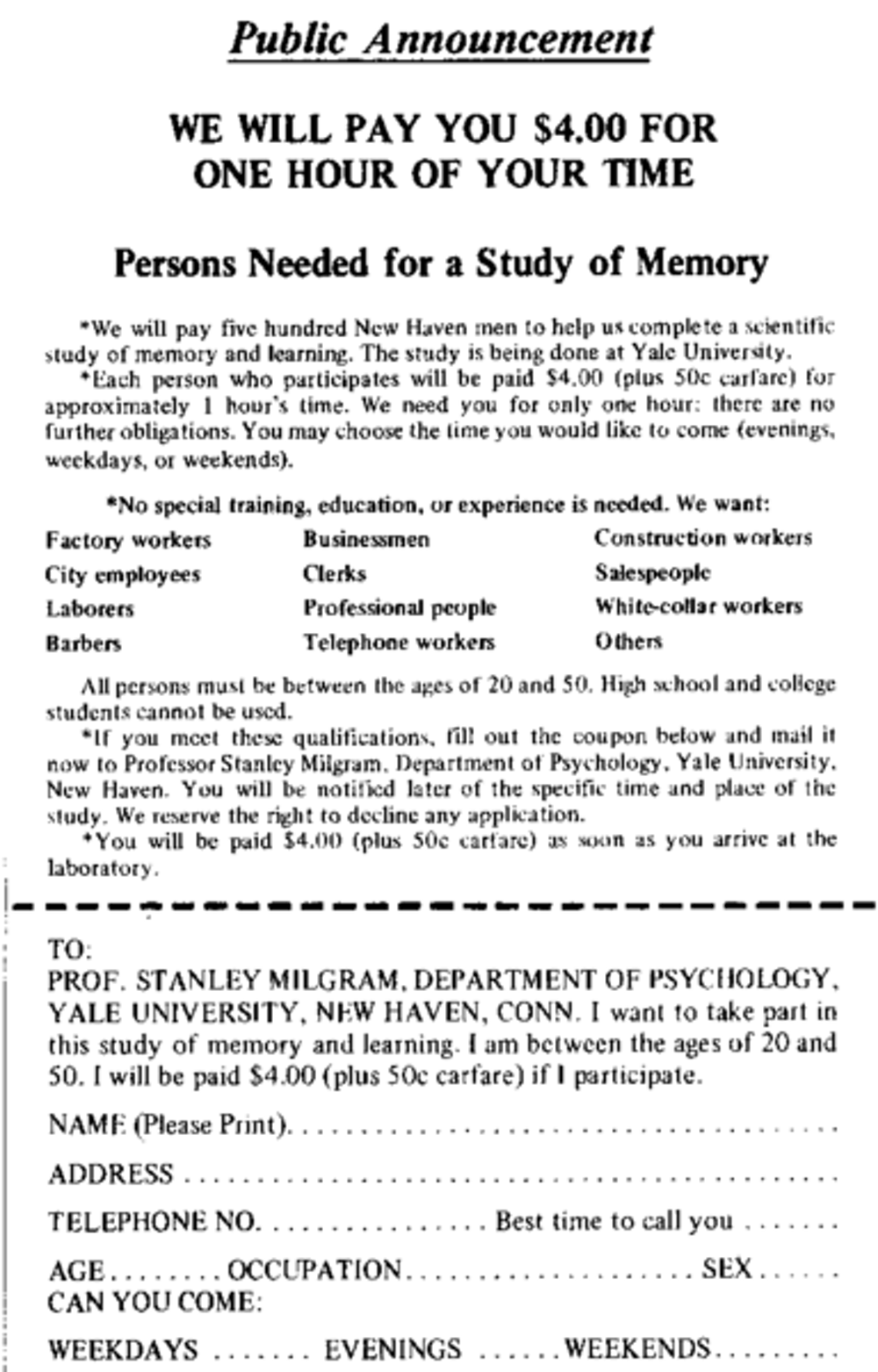

In the most famous his experiments, Milgram ostensibly recruited participants to take part in a study assessing the effects of pain on learning. In reality, he wanted to see how far he could push the average American to administer painful electric shocks to a fellow human being.

When participants arrived at his lab, Milgram’s assistant would ask them, as well as a second man, to draw slips of paper to receive their roles for the experiment. In fact, the second man was a confederate; the participant would always draw the role of “teacher,” and the second man would invariably be made the “learner.”

The participants received instructions to teach pairs of words to the confederate. After they had read the list of words once, the teachers were to test the learner’s recall by reading one word, and asking the learner to name one of the four words associated with it. The experimenter told the participants to punish any learner mistakes by pushing a button and administering an electric shock; while they could not see the learner, participants could hear his screams. The confederate, of course, remained unharmed, and merely acted out in pain, with each mistake costing him an additional 15 volts of punishment. In case participants faltered in their scientific resolve, the experimenter was nearby to urge them, using four authoritative statements:

Please continue.

The experiment requires that you continue.

It is absolutely essential that you continue.

You have no other choice, you must go on.

In a jarring set of findings, Milgram found that 26 of the 40 participants obeyed instructions, administering shocks all the way from “Slight Shock,” to “Danger: Severe Shock.” The final two ominous switches were simply marked “XXX.” Even when the learners would pound on the walls in agony after seemingly receiving 300 volts, participants persisted. Eventually, the learner simply stopped responding.

Although they followed instructions, participants repeatedly expressed their desire to stop the experiment, and showed clear signs of extreme discomfort:

“I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse… At one point he pushed his fist into his forehead and muttered: “Oh God, let’s stop it.” And yet he continued to respond to every word of the experimenter, and obeyed to the end.”

Milgram’s study set off a powder keg whose impact remains felt to this day. Ethically, many objected to the deception and the lack of adequate participant debriefing. Others claimed that Milgram overemphasized human nature’s propensity for blind obedience, with the experimenter often urging participants to continue many more times than the four stock phrases allowed.

In the clip above, you can watch original footage from Milgram’s experiment, frightening in its insidious simplicity. (See a full documentary on the study below.) The man administering the shock grows increasingly uncomfortable with his part in the proceedings, and almost walks out, asking “Who’s going to take the responsibility for anything that happens to that gentleman?” When the experimenter replies, “I’m responsible,” the man, absolving himself, continues. As the person receiving the shocks grows increasingly panicked, complaining about his heart and asking to be let out, the participant makes his objections known but appears paralyzed, sheepishly turning to the experimenter, unable to leave.

Although Milgram’s work has drawn critics, his results endure. While changing the experiment’s procedure may alter compliance (e.g., having the experimenter speak to participants over the phone rather than remain in the same room throughout the experiment decreased obedience rates), replications have tended to confirm Milgram’s initial findings. Whether one is urged once or a dozen times, people tend to take on the yoke of authority as absolute, relinquishing their personal agency in the pain they impart. Human nature, it seems, has no Manichean leanings—merely a pliant bent.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in November 2013.

Related Content:

Hermann Rorschach’s Original Rorschach Test: What Do You See? (1921)

Free Online Courses Psychology

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based science and culture writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman