How, exactly, does one go about making a global dictionary of symbols? It is a Herculean task, one few scholars would take on today, not only because of its scope but because the philological approach that gathers and compares artifacts from every culture underwent a correction: No one person can have the expertise to cover everything. Yet the attempts to do so have had tremendous creative value. Such explorations bring us closer to what makes humans the same the world over: our productive imaginations and the archetypal wellspring of images that guide us through the unknown.

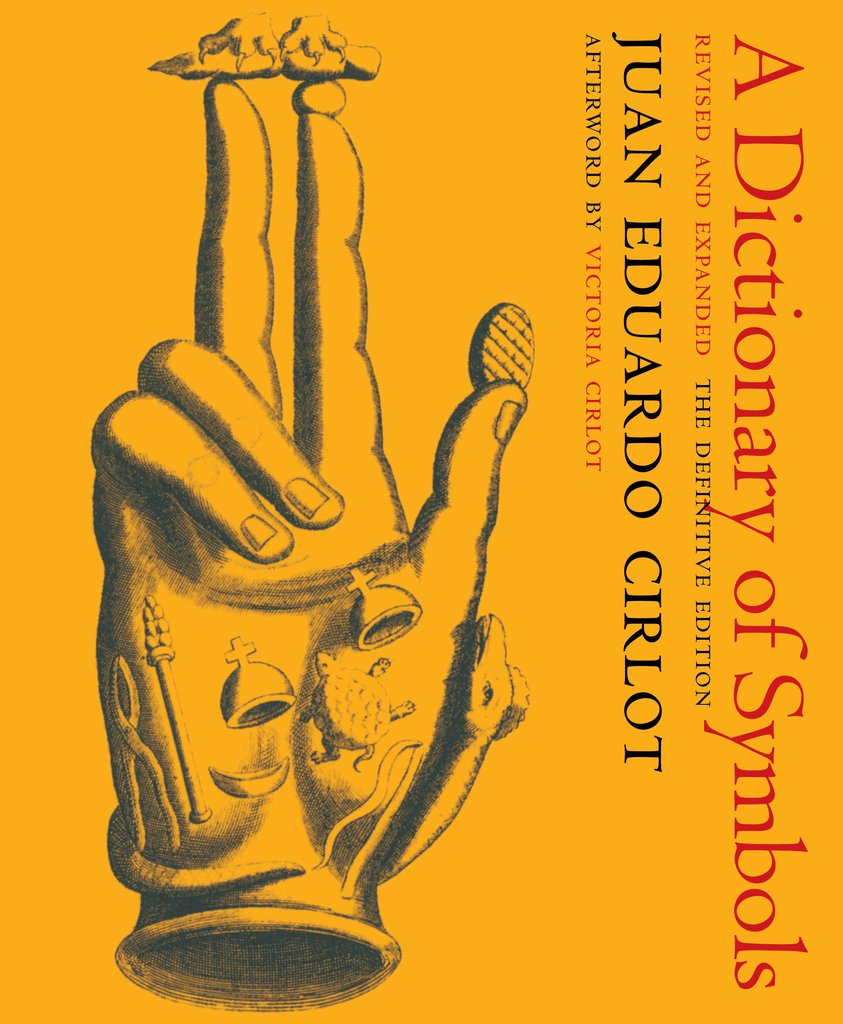

When Spanish poet, critic, translator, and musicologist Juan Eduardo Cirlot began his 1958 Dictionary of Symbols, he did so with Carl Jung in mind, writing against a current of positivism that devalued the symbolic.

Cirlot quotes Jung in his introduction: “For the modern mind, analogies… are nothing but self-evident absurdities. This worthy judgement does not, however, in any way alter the fact that such affinities of thought do exist and that they have been playing an important role for centuries.” Like it or not, we interact through the symbolic realm all the time. Those interactions are freighted with historical and cultural meaning we would do well to understand if we are to understand ourselves.

In his method, Cirlot writes in a Preface:

I wanted to embrace the broadest possible range of objects and cultures, to compare the symbols of the post-Roman West with symbols from India, the Far East, Chaldea, Egypt, Israel and Greece. Images, essential myths, allegories, for my purposes, all these needed to be consulted, not, self-evidently, with the intention of making an exhaustive reckoning, but rather to comb out patterns in meaning, in what counts as essential, in fields both near and far.

Cirlot draws his inspiration from Dada and Surrealism and the comparative method in religious studies popularized by scholars like Mircea Eliade, who influenced prominent students of myth like Joseph Campbell (and through Campbell, the popular culture of film, television, and the internet). “Thus I drew near the luminous labyrinth of symbols,” Cirlot writes, “concerned less with interpretation than with comprehension and concerned most of all, really, with the contemplation of how symbols dwell across time and culture.” And “dwell” they do, as we know, in elemental figures like dragons and serpents, destructive gods and evil eyes. (In 1954, Cirlot published The Eye in Mythology, a precursor to A Dictionary of Symbols.)

In times of trouble and uncertainty like ours, symbols become important ways of organizing chaos in our collective imagination, and are integral to what Sinding Bentzen, professor of economics at the University of Copenhagen, calls “religious coping” in the face of COVID-19. Ripped from their historic context, as happened with the swastika, symbols can be used to intentionally manipulate and mislead, to turn collective anxiety into acquiescence to tyranny and totalitarianism. Cirlot was acutely aware of this as an artist working under the rule of Francisco Franco. As a leading member of a group of painters and poets who called themselves Dau al Set (“the seven-spotted dice”), Cirlot and his contemporaries “championed creative liberty and resistance to the dominant Fascist regime.”

In the 21st century, we can just as well read Cirlot’s dictionary with this same mission. It is not an artifact of another time but as an ever-relevant, erudite, and fascinating resource for our own. Through the study of symbols we learn to see, Cirlot wrote, that “nothing is meaningless or neutral: everything is significant,” every idea connected to others across time and space. “It is only by reading through the volume steadily that one can become aware of the intricate interrelations of symbolic meanings,” wrote Catherine Rau in a 1962 review of the book. We can “develop such awareness by starting off with any random entry,” Angelica Frey observes at Hyperallergic.

Do so in the “original, significantly enlarged” new edition of the Cirlot’s Dictionary of Symbols, just published by the New York Review of Books in an English translation by Valerie Miles. We can read the book for reference or for pleasure, Herbert Read writes in an introduction to the new edition, “but in general the greatest use of the volume will be for the elucidation of those many symbols which we encounter in the arts and in the history of ideas. Man, it has been said, is a symbolizing animal; it is evident that at no stage in the development of civilization has man been able to dispense with symbols.”

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language

18 Classic Myths Explained with Animation: Pandora’s Box, Sisyphus & More

48 Hours of Joseph Campbell Lectures Free Online: The Power of Myth & Storytelling

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness