History resounds with events so momentous they can be conjured with a single word: Waterloo, Watergate, Tiananmen, Brexit.…

In the late nineteenth century, one simple phrase, J’Accuse!—the title of an open letter published by novelist Emile Zola—stood for a serious injustice that inflamed the political passions of artists, journalists, and the public for decades afterward, and presaged some of the 20th century’s most incredible state crimes.

Zola wrote in defense of French artillery captain Alfred Dreyfus, who was accused, court-marshalled, and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island for supposedly giving military secrets to the Germans. It was the trial of the century, writes Adam Gopnik at The New Yorker, and afterward, Dreyfus, “a young Jewish artillery officer and family man.… was publicly degraded before a gawking crowd.”

His insignia medals were stripped from him, his sword was broken over the knee of the degrader, and he was marched around the grounds in his ruined uniform to be jeered and spat at, while piteously declaring his innocence and his love of France above cries of “Jew” and “Judas!”

Two years later, compelling evidence came to light that showed another officer, Ferdinand Esterhazy, had committed the treasonous offence. But the evidence was buried, and the officer who found it transferred to North Africa and later imprisoned. The Dreyfus Affair marked a major turn in European civil society, “the moment where [Guy de] Maupassant’s world of ambition and pleasure met Kafka’s world of inexplicable bureaucratic suffering.” After a perfunctory two-day trial, Esterhazy was unanimously acquitted by a military court, and Dreyfus convicted of additional charges based on falsified documents.

Five years after Dreyfus’ conviction, his supporters, the “Dreyfusards,” including Zola, Henri Poincare, and Georges Clemenceau, forced the government to retry the case. Dreyfus was ultimately pardoned, and later fully exonerated and reinstated in the French army. He went on to serve with distinction in World War I.

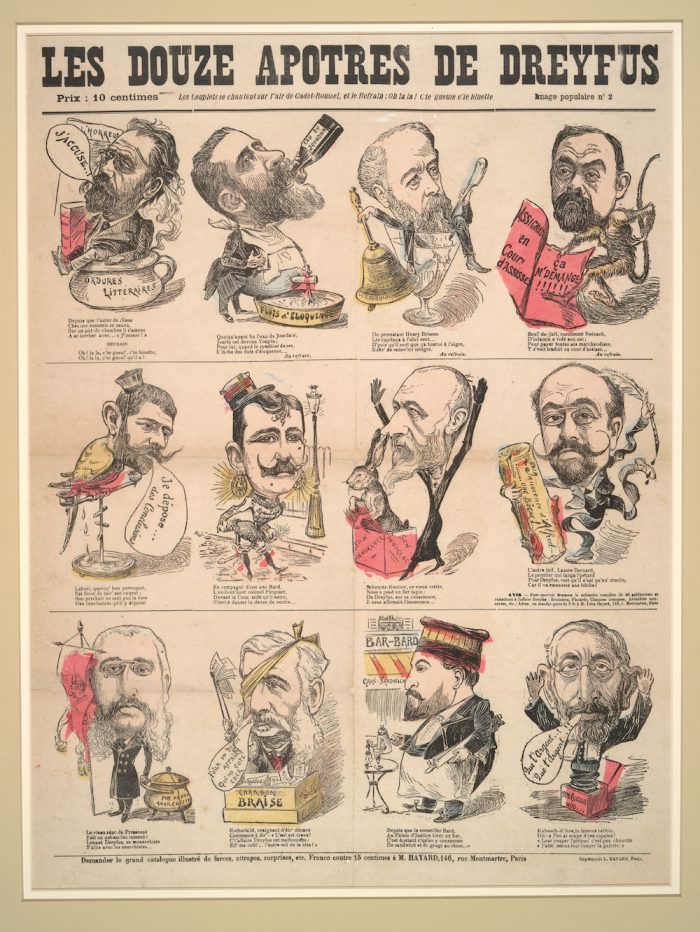

Dreyfus’ accusers’ have mostly sunk into obscurity. His supporters— some caricatured above as “the twelve apostles of Dreyfus”—included some of the most illustrious men of arts and letters in France. They can count among their number the great French director and cinematic visionary Georges Méliès. During the heated year of 1899, “Méliès made a series of eleven one-minute non-fiction films about the Dreyfus Affair as it was still unfolding,” writes Elizabth Ezra,” portraying sympathetically Dreyfus’ arrest,” imprisonment, and retrial. You can watch Méliès’ complete Dreyfus film at the top of the post.

It may be difficult to appreciate the daring of Méliès’ project from our historical distance, and in the somewhat alien idiom of silent film. “For today’s viewers,” writes Ezra, “it is not always easy to discern the sympathetic elements of the films, but the abundance of huffy gesturing and self-righteous facial expressions on the part of Dreyfus make of him a dignified hero who refuses to be degraded by the accusations made against him.” (In this respect, Méliès anticipated another silent film about another unjust trial in France, Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc.)

Likewise, we may find it hard to understand the significant social import of “Méliès’ only known expression of political commitment.” But to understand the Dreyfus Affair, we must understand, as the National Library of Israel points out, that “France was already a divided country and the case acted as a casus belli.… ‘The Jew from Alsace’ encapsulated all that the nationalist right loathed, and therefore became the symbol of the nation’s profound division.” Landing in the middle of this political firestorm, Méliès’ Dreyfus series “provoked partisan fistfights,” writes Ezra.

Not only did the Dreyfus case introduce into the public eye a vicious anti-Semitic show-trial, but it also served as a test case for censorship and media sensationalism. Méliès’ film, says author Susan Daitch in the On the Media episode above, was the first docudrama, the “first recreation based on photographs and illustrations in weekly newspapers in France at the time.” And it proved so controversial that it was banned, along with all other Dreyfus films, for fifty years, and only shown again in France in 1974.

The film, says Daitch—who has written a novel based on the Dreyfus Affair—emerged within a partisan mass media war of the kind we’re far too familiar with today. “Both sides,” Daitch tells us, “used and altered the media,” and Dreyfus was both successfully railroaded into prison and successfully retried and exonerated partly on the strength of his supporters’ and accusers’ propaganda campaigns.

The Dreyfus Affair will be added to our list of Free Silent Films, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

The film is considered to be in the public domain in the United States and comes to us via Wikimedia Commons.

Related Content:

The First Horror Film, George Méliès’ The Haunted Castle (1896)

Watch After the Ball, the 1897 “Adult” Film by Pioneering Director Georges Méliès (Almost NSFW)

Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) Gets an Epic, Instrumental Soundtrack from the Indie Band Joan of Arc

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness