Several friends and relatives of mine teach philosophy, writing, and critical thinking to undergraduate college students. And many of those people have confessed their dismay in recent months. Threats and McCarthyite attacks on higher educators have increased (and in places like Turkey escalated to full-on war against academics). Many educators are also filled with doubt about the meaning of their profession. How can they stand in the pulpits of higher learning, many wonder, extolling the virtues of clear expression, logic, reason and evidence, ethics, etc., when the world outside the classroom seems to be telling their students none of these things matter?

But then there are some with a more optimistic bent, who see more reason than ever to extol said virtues, with even more rigor and urgency. Philosophy improves our mental and emotional lives in every possible situation. While millions of people in supposedly democratic countries have decided to put their trust in autocratic, authoritarian leaders, millions more have determined to resist the curtailing of civil liberties, democratic rights, and social progress. Educators see the tools of language and critical thinking as integral to those of political action and civil disobedience. And not only do college students need these tools, argue the executives of UK’s Philosophy Foundation, but children do as well, and for many of the same reasons.

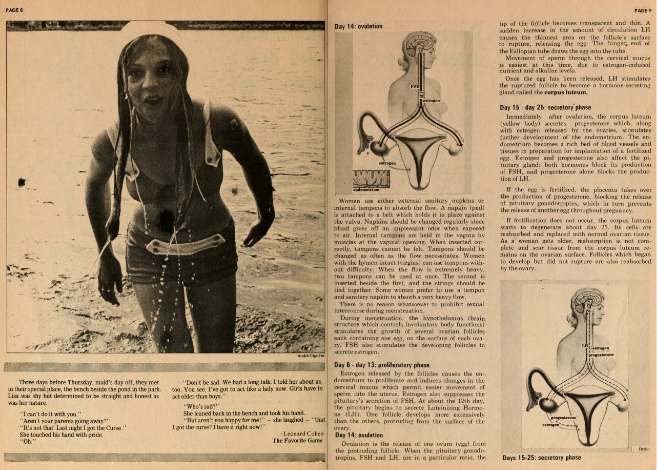

Created in 2007 to conduct “philosophical enquiry in schools, communities, and workplaces,” the Foundation works with both children and adults. In the Aeon Magazine video above, COO and CEO Emma and Peter Worley explain the special appeal of philosophy for kids, making the case for teaching “thinking well” at a young age. Rather than lecturing on the history of ideas or presenting a thesis, their approach involves getting children “thinking about things together, working together collaboratively, coming up with counter-examples… really doing philosophy in the true sense.” Young students see problems for themselves and apply their own philosophical solutions, using the nascent reasoning faculties most of us can access as soon as we’ve reached school age.

The Foundation has shown that the teaching of philosophy to children “has an impact on affective skills and also on cognitive skills.” In other words, kids become more emotionally intelligent as they become better thinkers, developing what Socrates called “the silent dialogue” with themselves. These benefits are goods in their own right, argues Emma Worley, and as valuable as the arts in our lives. “We need philosophy because it’s a human thing to do,” she says, “to think, to reason, to reflect.” But there is a decided social utility as well. Philosophy can “safeguard against the ways in which education might sometimes be used to control people,” says Peter Worley: “If we have something like philosophy within the system, something that steps outside that system and asks questions about it, then we have something to protect us” against authoritarian means of thought and language control.

via Aeon

Related Content:

Free Online Philosophy Courses, a subset of our collection 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

Noam Chomsky Defines What It Means to Be a Truly Educated Person

Henry Rollins Pitches Education as the Key to Restoring Democracy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness