Trauma is repetition, and the United States seems to inflict and suffer from the same deep wounds, repeatedly, unable to stop, like one of the ancient Biblical curses of which Bob Dylan was so fond. The Dylan of the early 1960s adopted the voice of a prophet, in various registers, to tell stories of judgment and generational curses, symbolic and historical, that have beset the country from its beginnings.

The verses of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” from 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, enact this repetition, both traumatic and hypnotic. In its dual refrains—“how many times…?” and “the answer is blowin’ in the wind” (ephemeral, impossible to grasp)—the song cycles between earnest Lamentations and the acute, world-weary resignation of Ecclesiastes. “This ambiguity is one reason for the song’s broad appeal,” as Peter Dreier writes at Dissent.

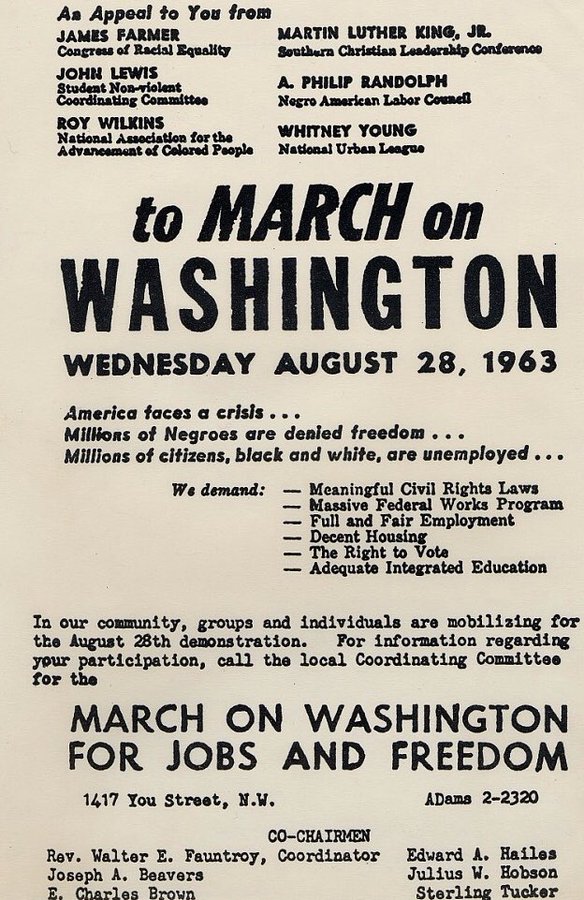

Just three months after its release, when Dylan performed at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, “Blowin’ in the Wind” had become a massive civil rights anthem. But he had already ceded the song to Peter, Paul & Mary, who played their version that day. Dylan ignored his sophomore album entirely to play songs from the upcoming The Times They Are a‑Changing—songs that stand out for their indictments of the U.S. in some very specific terms.

Dylan played three songs from the new album: “When the Ship Comes In” with Joan Baez, “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” and “With God on Our Side.” (He also played the popular folk song “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize.”) In contrast to his vaguely allusive popular anthems, “Only a Pawn in Their Game”—about the murder of Medgar Evers—isn’t coy about the culprits and their crimes. We might say the song offers an astute analysis of institutional racism, white supremacy, and stochastic terrorism.

A bullet from the back of a bush

Took Medgar Evers’ blood

A finger fired the trigger to his name

A handle hid out in the dark

A hand set the spark

Two eyes took the aim

Behind a man’s brain

But he can’t be blamed

He’s only a pawn in their gameA South politician preaches to the poor white man

“You got more than the blacks, don’t complain

You’re better than them, you been born with white skin, ” they explain

And the Negro’s name

Is used, it is plain

For the politician’s gain

As he rises to fame

And the poor white remains

On the caboose of the train

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their gameThe deputy sheriffs, the soldiers, the governors get paid

And the marshals and cops get the same

But the poor white man’s used in the hands of them all like a tool

He’s taught in his school

From the start by the rule

That the laws are with him

To protect his white skin

To keep up his hate

So he never thinks straight

‘Bout the shape that he’s in

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their gameFrom the poverty shacks, he looks from the cracks to the tracks

And the hoofbeats pound in his brain

And he’s taught how to walk in a pack

Shoot in the back

With his fist in a clinch

To hang and to lynch

To hide ‘neath the hood

To kill with no pain

Like a dog on a chain

He ain’t got no name

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their gameToday, Medgar Evers was buried from the bullet he caught

They lowered him down as a king

But when the shadowy sun sets on the one

That fired the gun

He’ll see by his grave

On the stone that remains

Carved next to his name

His epitaph plain

Only a pawn in their game

These lyrics have far too much relevance to current events, and they’re indicative of the changing tone of Dylan’s muse. His refrains drip with irony. The killer of Medgar Evers “can’t be blamed”—an evasion of responsibility that becomes a powerful force all its own.

Dylan revisits the themes of generational trauma and murder in “With God on Our Side” (hear him sing it with Baez at Newport, above). The song is a sharp satire of his historical education, with its inevitable repetitions of war and slaughter. Here, Dylan presents the exponentially gross, existentially dreadful, consequences of a national abdication of blame for historical violence.

Oh my name it ain’t nothin’

My age it means less

The country I come from

Is called the Midwest

I was taught and brought up there

The laws to abide

And that land that I live in

Has God on its sideOh, the history books tell it

They tell it so well

The cavalries charged

The Indians fell

The cavalries charged

The Indians died

Oh, the country was young

With God on its sideThe Spanish-American

War had its day

And the Civil War, too

Was soon laid away

And the names of the heroes

I was made to memorize

With guns in their hands

And God on their sideThe First World War, boys

It came and it went

The reason for fighting

I never did get

But I learned to accept it

Accept it with pride

For you don’t count the dead

When God’s on your sideThe Second World War

Came to an end

We forgave the Germans

And then we were friends

Though they murdered six million

In the ovens they fried

The Germans now, too

Have God on their sideI’ve learned to hate the Russians

All through my whole life

If another war comes

It’s them we must fight

To hate them and fear them

To run and to hide

And accept it all bravely

With God on my sideBut now we got weapons

Of chemical dust

If fire them, we’re forced to

Then fire, them we must

One push of the button

And a shot the world wide

And you never ask questions

When God’s on your sideThrough many a dark hour

I’ve been thinkin’ about this

That Jesus Christ was

Betrayed by a kiss

But I can’t think for you

You’ll have to decide

Whether Judas Iscariot

Had God on his side.So now as I’m leavin’

I’m weary as Hell

The confusion I’m feelin’

Ain’t no tongue can tell

The words fill my head

And fall to the floor

That if God’s on our side

He’ll stop the next war

Dylan’s race/class analysis in “Only a Pawn in the Game” and his succinct People’s History of Christian Nationalism in “With God on Our Side” stand out as interesting choices for the March for several reasons. For one thing, it’s as though he had written these songs expressly to take the political, economic, and religious mechanisms and mythologies of racism apart. This was radical speech in an event that was policed by its organizers to tone down inflammatory rhetoric for the cameras.

23-year-old John Lewis, for example, was forced to temper his speech, in which he meant to say, “We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently.… the revolution is at hand, and we must free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery.” As a popular white artist, rather than a potentially seditious Black organizer, Dylan had far more license and could “use his privilege,” as they say, to describe the systems of political and economic oppression Lewis had wanted to name.

Dylan’s performance was one of a handful of memorable musical appearances. Most of the singers made a far bigger impression, like Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, and Baez herself, whose “We Shall Overcome” created a legendary moment of harmony. No one sang along to Dylan’s new songs—they wouldn’t have known the words. But Dylan was never careless. He chose these words for the moment, hoping to have some impact in the only way he could.

The 1963 March’s purpose has been overshadowed by a few passages in Martin Luther King, Jr.‘s powerful “I Have a Dream” speech, co-opted by everyone and reduced to meme-able quotes. But the protest “remains one of the most successful mobilizations ever created by the American Left,” historian William P. Jones writes. “Organized by a coalition of trade unionists, civil rights activists, and feminists–most of them African American and nearly all of them socialists.”

Dylan sang stories of how the country got to where it was, through a history of violence still playing out before the marchers’ eyes. Whatever political tensions there were among the various organizers and speakers did not distract them from pushing through the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Fair Employment Practices clause banning discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, or sex—protections that have been broadened since that time, and also challenged, threatened, and stripped away.

Fifty-seven years later, as the RNC convention ends and another March on Washington happens, we might reflect on Dylan’s small but prescient contributions in 1963, in which he aptly characterized the traumatic repetitions we’re still convulsively experiencing over half a century later.

Related Content:

A Massive 55-Hour Chronological Playlist of Bob Dylan Songs: Stream 763 Tracks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness