Sylvia Plath would have turned 81 years old today. It’s a strange thing to imagine. Plath’s reputation as a poet is so sadly bound up with her death by suicide at the age of 30, and so many of the lines in her later poetry sound like suicide notes, that it seems impossible to picture her making it to old age. In “Lady Lazarus,” Plath writes: “Dying/Is an art, like everything else./I do it exceptionally well.”

Plath is remembered mainly for the poems she wrote in the last half year of her life, when she had separated from her husband, the poet Ted Hughes. It was then that Plath found her “real voice,” as Hughes put it, in a marathon burst of creativity that resulted in the composition of some 70 poems, over half of which were collected in her posthumous book, Ariel.

But the circumstances surrounding Plath’s final days–her anger and sense of betrayal over her husband’s infidelity, her decision to kill herself by turning on the gas and placing her head in an unlighted oven while her two young children slept in another room–have complicated her literary legacy. A morbid cult has surrounded Plath, with many of her most fervent admirers glossing over the poet’s long struggle with mental illness to find in her a martyred feminist saint, a modern Ophelia.

“It has frequently been asked whether the poetry of Plath would have so aroused the attention of the world if Plath had not killed herself,” writes Janet Malcolm in The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. “I would agree with those who say no. The death-ridden poems move us and electrify us because of our knowledge of what happened.” It’s a shame, because Plath’s achievement should be judged on its own merits. In 2000, Joyce Carol Oates described some of the qualities she admired in Plath’s writing:

The most memorable of Sylvia Plath’s incantatory poems, many of them written during the final, turbulent weeks of her life, read as if they’ve been chiseled, with a fine surgical instrument, out of Arctic ice. Her language is taught and original; her strategy eliptical; such poems as “Lesbos,” “The Munich Mannequins,” “Paralytic,” “Daddy” (Plath’s most notorious poem), and “Edge” (Plath’s last poem, written in February, 1963), and the prescient “Death & Co.” linger long in the memory, with the power of malevolent nursery rhymes. For Plath, “The blood jet is poetry,” and readers who might know little of the poet’s private life can nonetheless feel the authenticity of Plath’s recurring emotions: hurt, bewilderment, rage, stoic calm, bitter resignation. Like the greatest of her predecessors, Emily Dickinson, Plath understood that poetic truth is best told slantwise, in as few words as possible.

Oates called Plath “our acknowledged Queen of Sorrows, the spokeswoman for our most private, most helpless nightmares.” The poem above, “A Birthday Present,” is one of the private and nightmarish poems collected in Ariel. Plath wrote it just over half a century ago as she was contemplating the approach of her 30th birthday, and something darker. The recording is from a BBC broadcast in December of 1962, only two months before Plath’s death. (You can read the text as you listen.) In his 1966 foreward to the first U.S. edition of Ariel, the poet Robert Lowell made the following assessment of Plath:

Suicide, father-hatred, self-loathing–nothing is too much for the macabre gaiety of her control. Yet it is too much; her art’s immortality is life’s disintegration. The surprise, the shimmering, unwrapped birthday present, the transcendence “into the red eye, the cauldron of morning,” and the lover, who are always waiting for her, are Death, her own abrupt and defiant death.

Related Content:

Dylan Thomas Recites ‘Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night’ and Other Poems

Charles Bukowski Reads His Poem “The Secret of My Endurance”

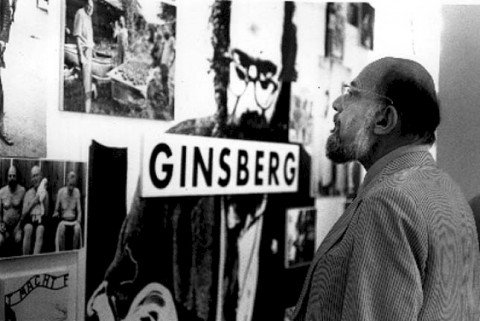

Allen Ginsberg Reads His Famously Censored Beat Poem, Howl

Hear Sylvia Plath Read Fifteen Poems From Her Final Collection, Ariel, in 1962 Recording