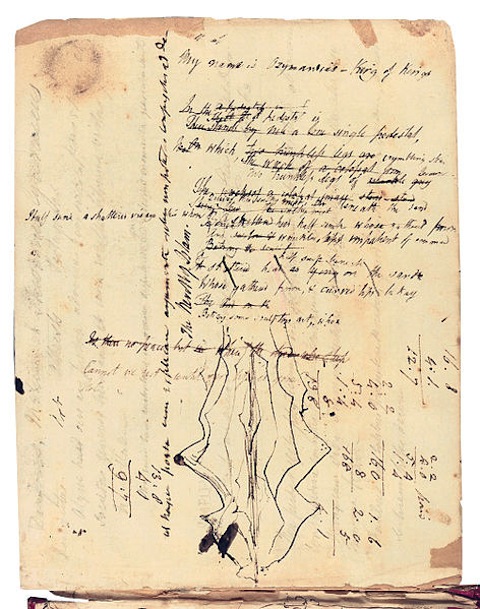

The outspoken, ragged-edged poet and novelist Charles Bukowski entered our world 93 years ago this Friday, and presumably began making trouble immediately. HarperCollins marks the occasion a bit early this year by releasing today eight Bukowski audiobooks, the first of their kind. (Sign up for a Free Trial with Audible.com and you can get one for free.) Alas, Bukowski didn’t live quite long enough to commit Post Office, South of No North, Factotum, Women, Ham on Rye, Hot Water Music, Hollywood, and Pulp to tape himself. ”

It would be Bukowski himself reading here, if the technology had advanced quickly enough,” Galleycat quotes publisher Daniel Halpern as saying, “but his voice rings clear and deep in these renditions – and from them, the genius of Bukowski flows forth.” Whether or not you plan to purchase these new audiobooks, we offer you here a dose of Bukowski out loud.

At the top you’ll find one of Bukowski’s own readings, “The Secret of My Endurance,” a poem that appeared in Dangling In The Tournefortia (1982). Down below you can hear Bukowski’s “Nirvana” as read by Tom Waits, who possesses a voice famously evocative of unforgiving American life, one that perhaps sounds more like that of a Bukowski poem than Bukowski’s own. And if you missed our earlier post featuring Waits’ interpretation of “The Laughing Heart (middle),” what more suitable occasion could you have to circle back and heed its battered yet optimistic guidance: “Your life is your life. Don’t let it be clubbed into dank submission.”

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

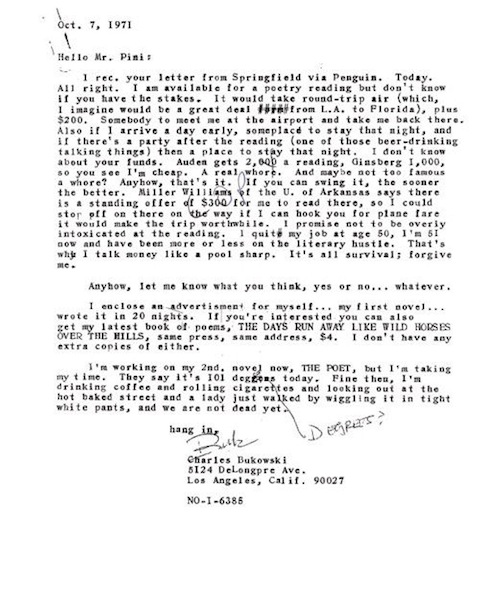

Charles Bukowski Sets His Amusing Conditions for Giving a Poetry Reading (1971)

“Don’t Try”: Charles Bukowski’s Concise Philosophy of Art and Life

Charles Bukowski: Depression and Three Days in Bed Can Restore Your Creative Juices (NSFW)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.