The Middle East is hardly the world’s most harmonious region, and it only gets more fractious if you add in South Asia and the Mediterranean. But there’s one thing on which many residents of that wide geographical span can agree: Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī. One might at first imagine that a thirteenth-century poet and mystical philosopher who wrote in Persian, with occasional forays into Turkish, Arabic, and Greek, would be a niche figure today, if known at all. In fact, Rumi, as he’s commonly known, is now one of the most popular writers in not just the Middle East but the world; English reinterpretations of his verse have even made him the best-selling poet in the United States.

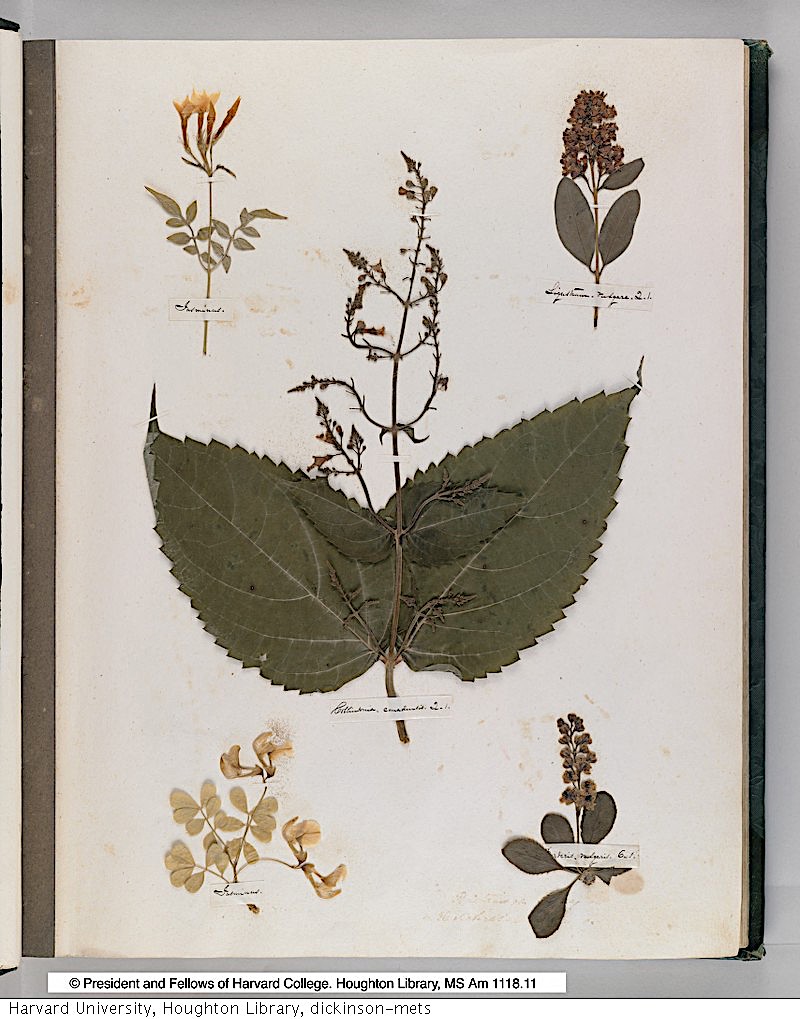

“The transformative moment in Rumi’s life came in 1244, when he met a wandering mystic known as Shams of Tabriz,” writes the BBC’s Jane Ciabattari. She quotes Brad Gooch, author of Rumi’s Secret: The Life of the Sufi Poet of Love, describing them as having an “electric friendship for three years,” after which Shams disappeared. “Rumi coped by writing poetry,” which includes 3,000 poems written for “Shams, the prophet Muhammad and God. He wrote 2,000 rubayat, four-line quatrains. He wrote in couplets a six-volume spiritual epic, The Masnavi.” He did all this work in service of what, in the animated TED-Ed lesson above, Stephanie Honchell Smith calls his ultimate goal: “the reunification of his soul with God through the experience of divine love.”

How is such a love to be accessed? “Love resides not in learning, not in knowledge, not in pages in books,” Rumi declared. “Wherever the debates of men may lead, that is not the lover’s path.” He pursued it through devotion to Shams’ Sufism, “participating in ritualized dancing and preaching the religion of love through lectures, poetry, and prose.” Later in life, he shifted “from ecstatic expressions of divine love to verses that guide others to discover it for themselves,” incorporating “ideas, stories, and quotes from Islamic religious texts, Arabic and Persian literature and earlier Sufi writings and poetry.” Perhaps there can be no full appreciation of Rumi’s work without a scholar’s understanding of the languages and cultures he knew. But if his sales figures are anything to go by, the longing into which his complex work taps is universal.

Related content:

The Mystical Poetry of Rumi Read By Tilda Swinton, Madonna, Robert Bly & Coleman Barks

The Complex Geometry of Islamic Art & Design: A Short Introduction

500+ Beautiful Manuscripts from the Islamic World Now Digitized & Free to Download

The Birth and Rapid Rise of Islam, Animated (622‑1453)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.