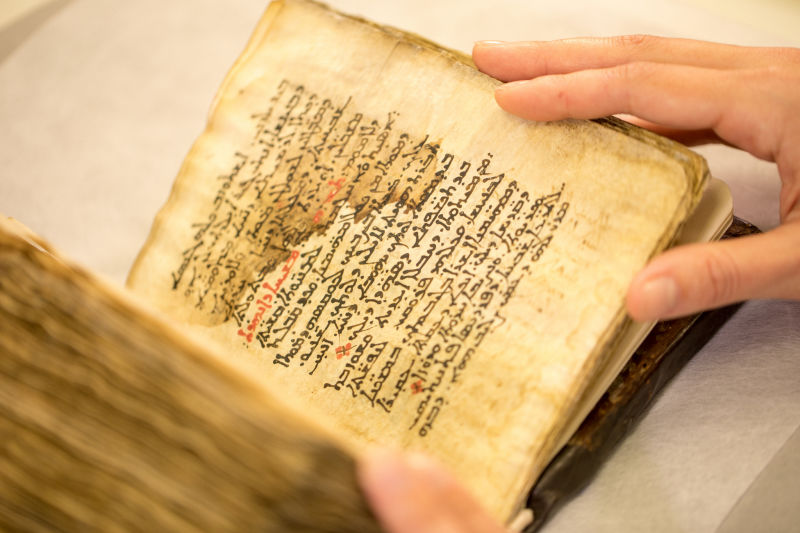

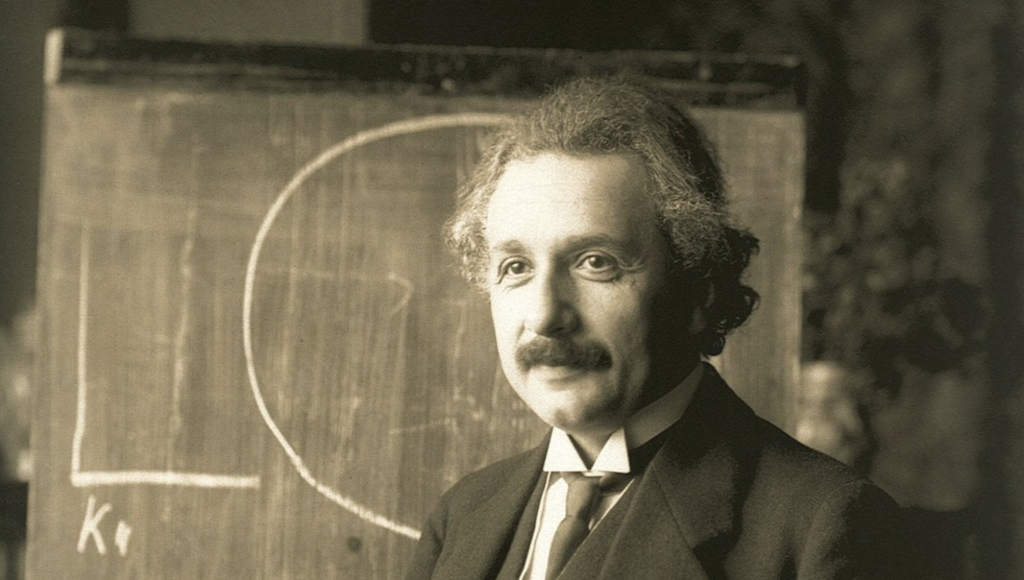

Albert Einstein, 1921, by Ferdinand Schmutzer via Wikimedia Commons

Here’s an extraordinary recording of Albert Einstein from the fall of 1941, reading a full-length essay in English:

The essay is called “The Common Language of Science.” It was recorded in September of 1941 as a radio address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The recording was apparently made in America, as Einstein never returned to Europe after emigrating from Germany in 1933.

Einstein begins by sketching a brief outline of the development of language, before exploring the connection between language and thinking. “Is there no thinking without the use of language,” asks Einstein, “namely in concepts and concept-combinations for which words need not necessarily come to mind? Has not every one of us struggled for words although the connection between ‘things’ was already clear?”

Despite this evident separation between language and thinking, Einstein quickly points out that it would be a gross mistake to conclude that the two are entirely independent. In fact, he says, “the mental development of the individual and his way of forming concepts depend to a high degree upon language.” Thus a shared language implies a shared mentality. For this reason Einstein sees the language of science, with its mathematical signs, as having a truly global role in influencing the way people think:

The supernational character of scientific concepts and scientific language is due to the fact that they have been set up by the best brains of all countries and all times. In solitude, and yet in cooperative effort as regards the final effect, they created the spiritual tools for the technical revolutions which have transformed the life of mankind in the last centuries. Their system of concepts has served as a guide in the bewildering chaos of perceptions so that we learned to grasp general truths from particular observations.

Einstein concludes with a cautionary reminder that the scientific method is only a means toward an end, and that the welfare of humanity depends ultimately on shared goals.

Perfection of means and confusion of goals seem–in my opinion–to characterize our age. If we desire sincerely and passionately for the safety, the welfare, and the free development of the talents of all men, we shall not be in want of the means to approach such a state. Even if only a small part of mankind strives for such goals, their superiority will prove itself in the long run.

The immediate context of Einstein’s message was, of course, World War II. The air force of Einstein’s native country had only recently called off its bombing campaign against England. A year before, London weathered 57 straight nights of bombing by the Luftwaffe. Einstein had always felt a deep sense of gratitude to the British scientific community for its efforts during World War I to test the General Theory of Relativity, despite the fact that its author was from an enemy nation.

“The Common Language of Science” was first published a year after the radio address, in Advancement of Science 2, no. 5. It is currently available in the Einstein anthologies Out of My Later Years and Ideas and Opinions.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in March 2013.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Find Courses on Einstein in the Physics Section of our Free Online Courses Collection