Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman is “famous in a number of dimensions,” says science and math explainer Grant Sanderson of the YouTube channel 3blue1brown in the video above. “To scientists, he’s a giant of 20th century physics… to the public, he’s a refreshing contradiction to the stereotypes about physicists: a safe-cracking, bongo-playing, mildly philandering non-conformist.” Feynman is also famous, or infamous, for his role in the Manhattan Project and the building of the first atomic bomb, after which the FBI kept tabs on him to make sure he wouldn’t, like his colleague Klaus Fuchs, turn over nuclear secrets to the Soviets.

He may have led an exceptionally eventful life for an academic scientist, but to his students, he was first and foremost “an exceptionally skillful teacher… for his uncanny ability to make complicated topics feel natural and approachable.” Feynman’s teaching has since influenced millions of readers of his wildly popular memoirs and his lecture series, recorded at Caltech and published in three volumes in the early 1960s. (Also see his famous course taught at Cornell.) For decades, Feynman fans could list offhand several examples of the physicist’s acumen for explaining complex ideas in simple, but not simplistic, terms.

But it wasn’t until the mid-nineties that the public had access to one of the finest of his Caltech lectures. Discovered in the 1990s and first published in 1996, the “lost lecture”—titled “The Motion of the Planets Around the Sun”—“uses nothing more than advanced high school geometry to explain why the planets orbit the sun elliptically rather than in perfect circles,” as the Amazon description summarizes. You can purchase a copy for yourself, or hear it Feynman deliver for free just below.

Feynman gave the talk as the guest speaker in a 1964 freshman physics class. He addresses them, he says, “just for the fun of it”; none of the material would be on the test. Nevertheless, he ended up hosting an informal 20-minute Q&A afterwards. Given his audience, Feynman assumes only the most basic prior knowledge of the subject: an explanation for why the planets make elliptical orbit around the sun. “It ultimately has to do with the inverse square law,” says Sanderson, “but why?”

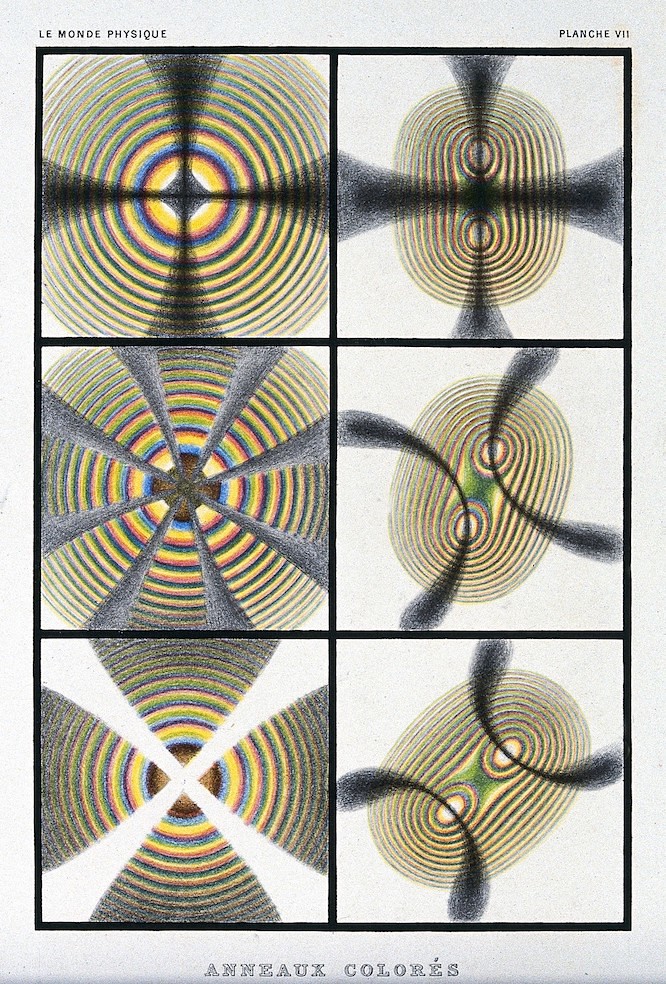

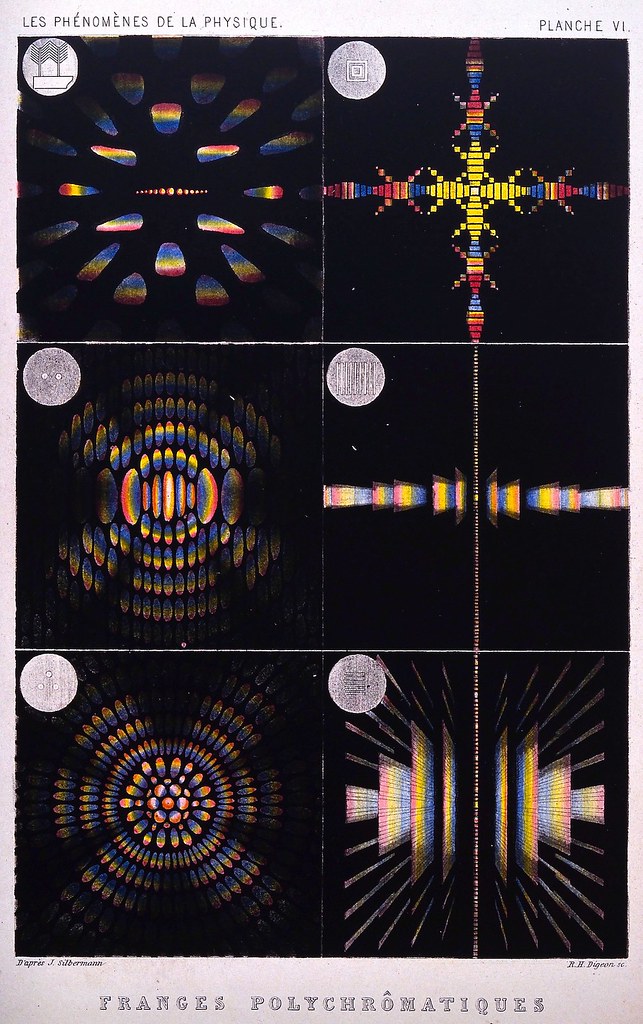

Part of the problem with the lecture, as its discoverers David and Judith Goodstein—husband and wife physicist and archivist at Caltech—found, involves Feynman’s extensive reference to figures he draws on the blackboard. It took some time for the two to dig these diagrams up in a set of class notes. In Sanderson’s video at the top, we get something perhaps even better: animated physical representations of the mathematics that determine planetary motion. We need not know this math in depth to grasp what Feynman calls his “elementary” explanation.

“Elementary” in this case, despite common usage, does not mean “easy,” Feynman says. It means “that very little is required to know ahead of time in order to understand it, except to have an infinite amount of intelligence.” That last part is a typical bit of humor. Even those of who haven’t pursued math or physics much beyond the high school level can learn the basic outlines of planetary motion in Feynman’s witty lecture, supplemented by the video visual aids Sanderson offers at the top.

Related Content:

Learn How Richard Feynman Cracked the Safes with Atomic Secrets at Los Alamos

Richard Feynman on the Bongos

Richard Feynman Plays the Bongos

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness