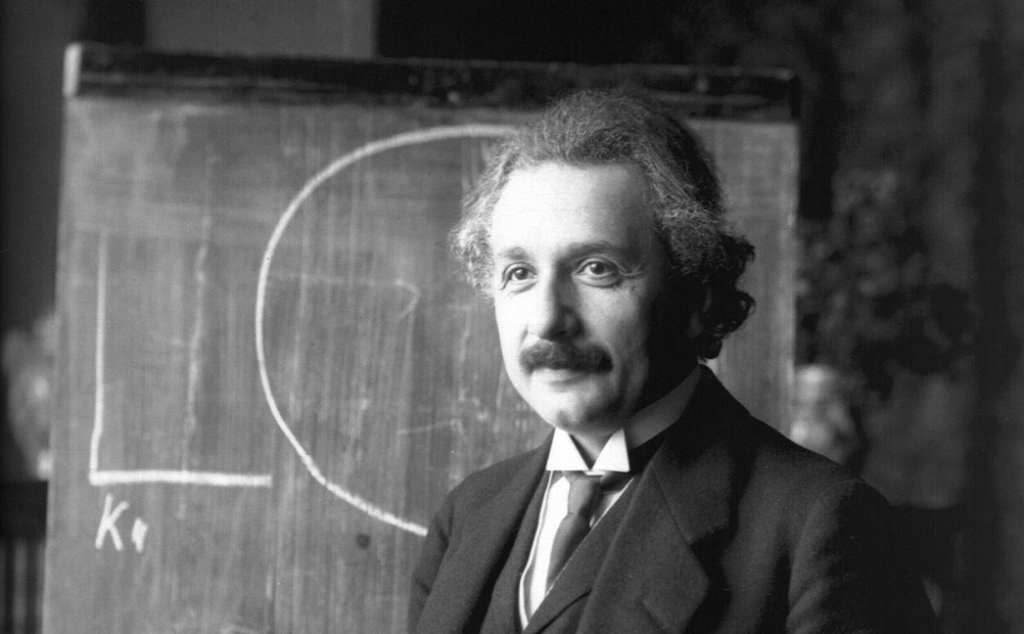

As one particularly astute observer of human emotions might put it, it is a truth universally acknowledged that we can’t all be Albert Einstein. In fact, none of us can. That unique experience was denied even Einstein’s son Hans Albert, though he did go on to his own distinguished career as an engineer and professor of hydraulics. Einstein father and son had a strained relationship, yet the great physicist had a hand in his son’s success, inspiring him to pursue his scientific passion. But Einstein’s paternal encouragement extended further, beyond scientific pursuits and to a general theory of learning and enjoyment that suggests we can be happiest and most productive when being most ourselves.

While living in Berlin in 1915, Einstein wrote a poignant letter to his son, just two days after finishing his theory of general relativity. His tone swings from buoyant to pained—lamenting his family’s “awkward” separation and proposing to spend more time with Albert, as he calls him. His son can “learn many good and beautiful things from me,” writes Einstein, “These days I have completed one of the most beautiful works of my life.”

Einstein also writes, “I am very pleased that you find joy with the piano. This and carpentry are in my opinion for your age the best pursuits.” An amateur musician himself, Einstein understood the value of developing an informal avocation. “Mainly play the things on the piano which please you,” he tells his son, “even if the teacher does not assign those.” Doing what you love, the way you like to do it, he goes on, “is the way to learn the most, that when you are doing something with such enjoyment that you don’t notice that the time passes.”

This great theme of total immersion in a creative endeavor surfaced several decades later in another scientist’s work, that of Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, described by Martin Seligman—former President of the American Psychological Association—as “the world’s leading researcher” in the field of positive psychology. Presented in his popular TED talk above, and at more length in his books on the subject, Csikszentmihalyi’s insights into human flourishing mirror Einstein’s: he calls such creative immersion “flow,” or the state of “being completely involved in an activity for its own sake.”

The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.

Contrary to our usual conceptions of using one’s “skills to the utmost,” Csikszentmihalyi tells us that the reward for entering such a state is not the material benefits it generates, but the positive emotions. These, as Einstein theorized, not only motivate us to become better, but they also provide a source of meaning no amount of financial gain above a minimum level can offer. “The lack of basic material resources contributes to unhappiness,” Csikszentmihalyi’s data demonstrates, “but the increase in material resources does not increase happiness.” While none of us can be Einstein, Csikszentmihalyi tells us we can all benefit from Einstein’s advice, by doing whatever we do to the best of our abilities and without any motive other than sheer pleasure.

via Farnam Street/Brain Pickings

Related Content:

The Musical Mind of Albert Einstein: Great Physicist, Amateur Violinist and Devotee of Mozart

Listen as Albert Einstein Calls for Peace and Social Justice in 1945

Albert Einstein Reads ‘The Common Language of Science’ (1941)

Free Online Psychology Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness