No matter how many public institutions you visit in a day—schools, libraries, museums, or the dreaded DMV—you may still feel like privatized services are closing in. And if you’re a fan of national parks and public lands, you’re keenly aware they’re at risk of being eaten up by developers and energy companies. The commons are shrinking, a tragic fact that is hardly inevitable but, as Matto Mildenberger argues at Scientific American, the result of some very narrow ideas.

But we can take heart that one store of common wealth has majorly expanded recently, and will continue to grow each year since January 1, 2019—Public Domain Day—when hundreds of thousands of works from 1923 became freely available, the first time that happened in 21 years. This year saw the release of thousands more works into the public domain from 1924, and so it will continue ad infinitum.

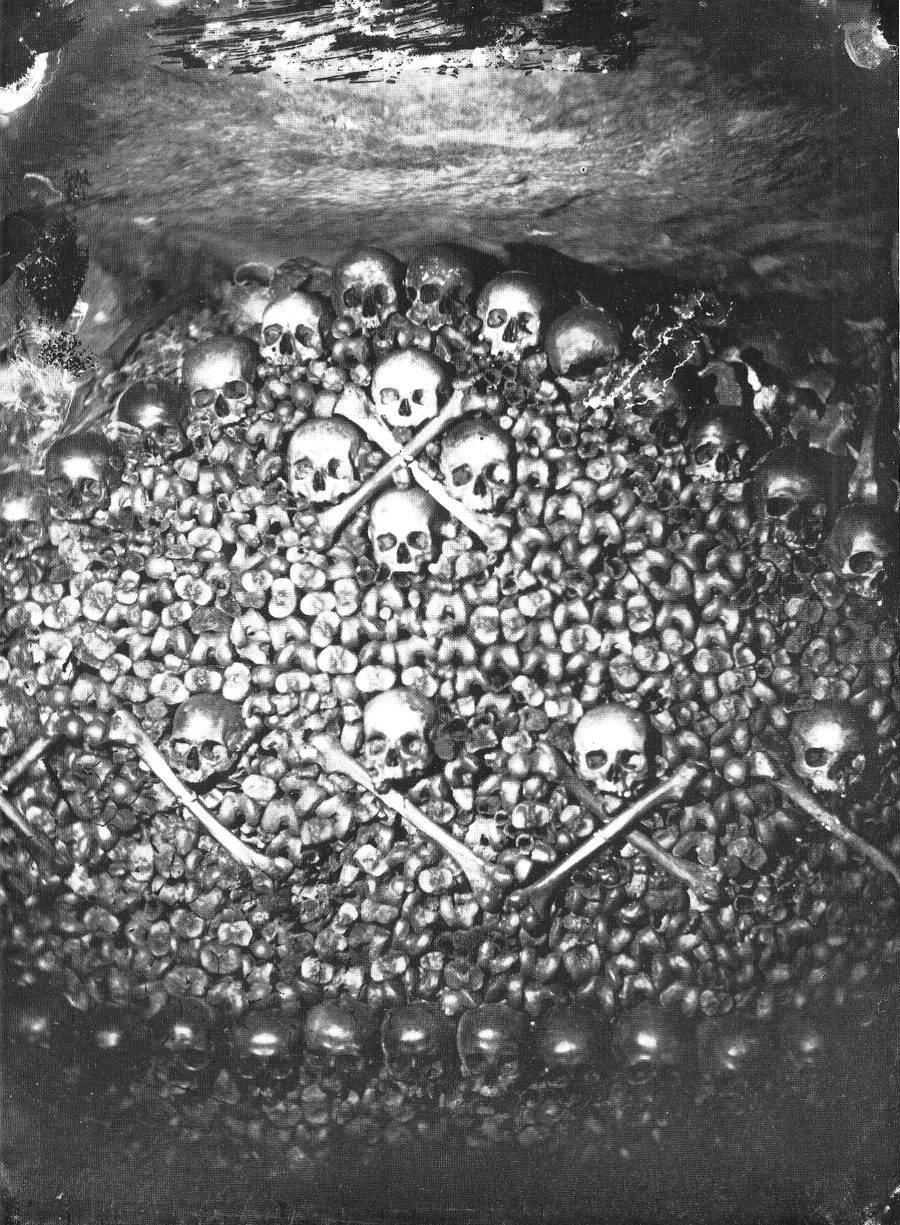

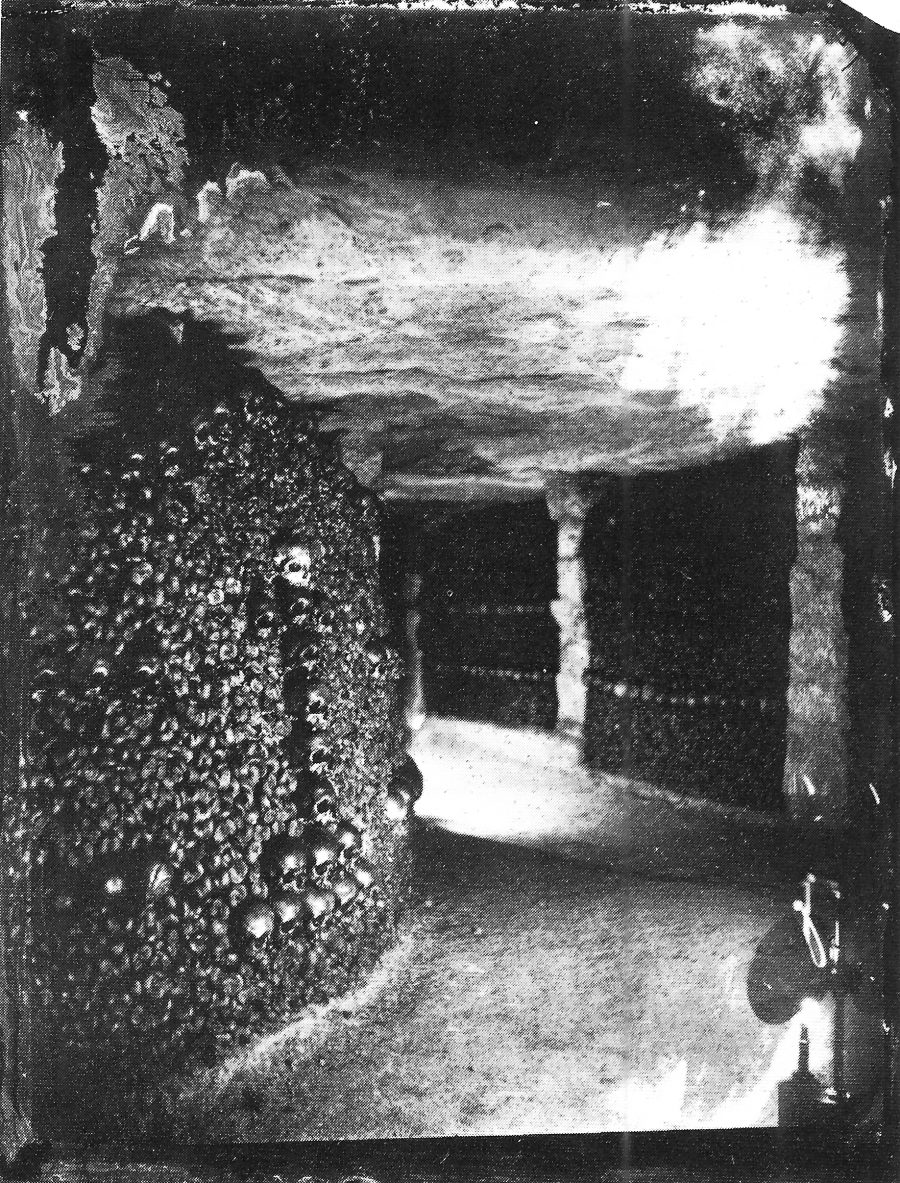

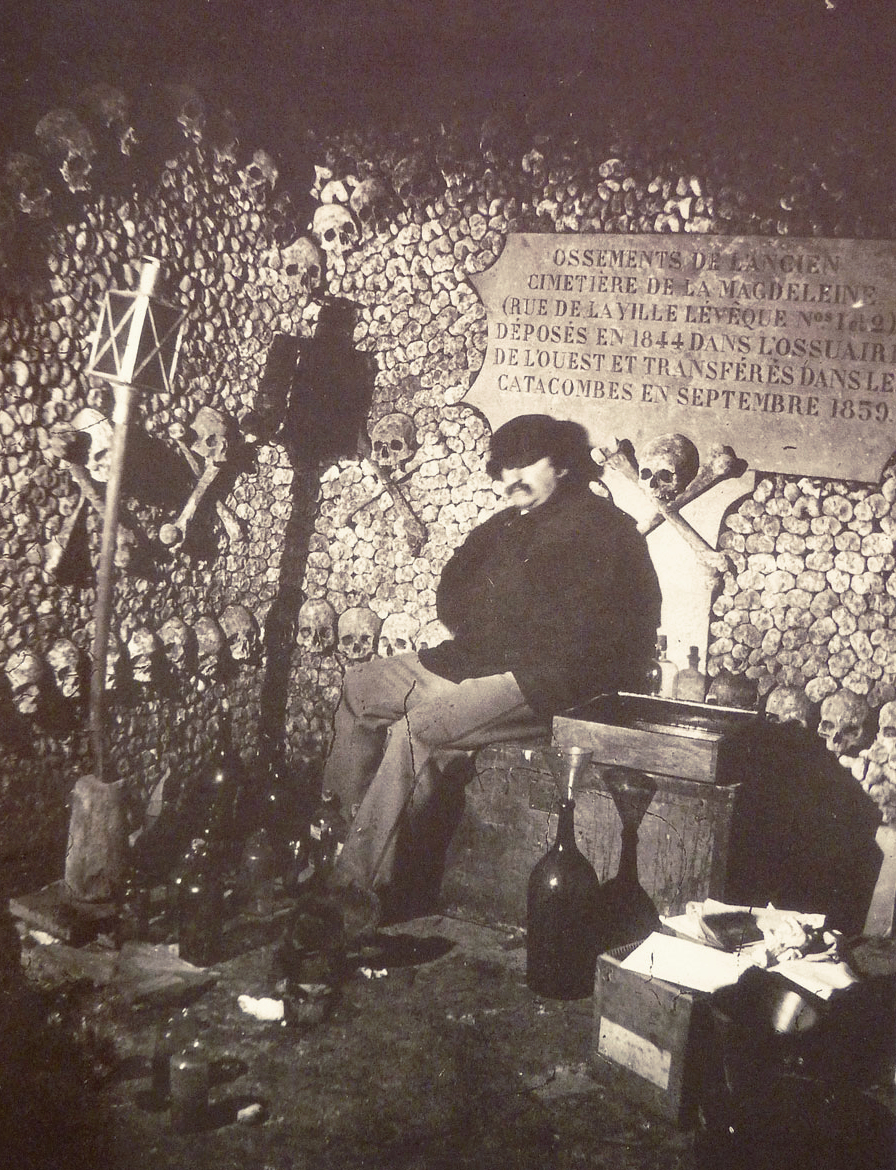

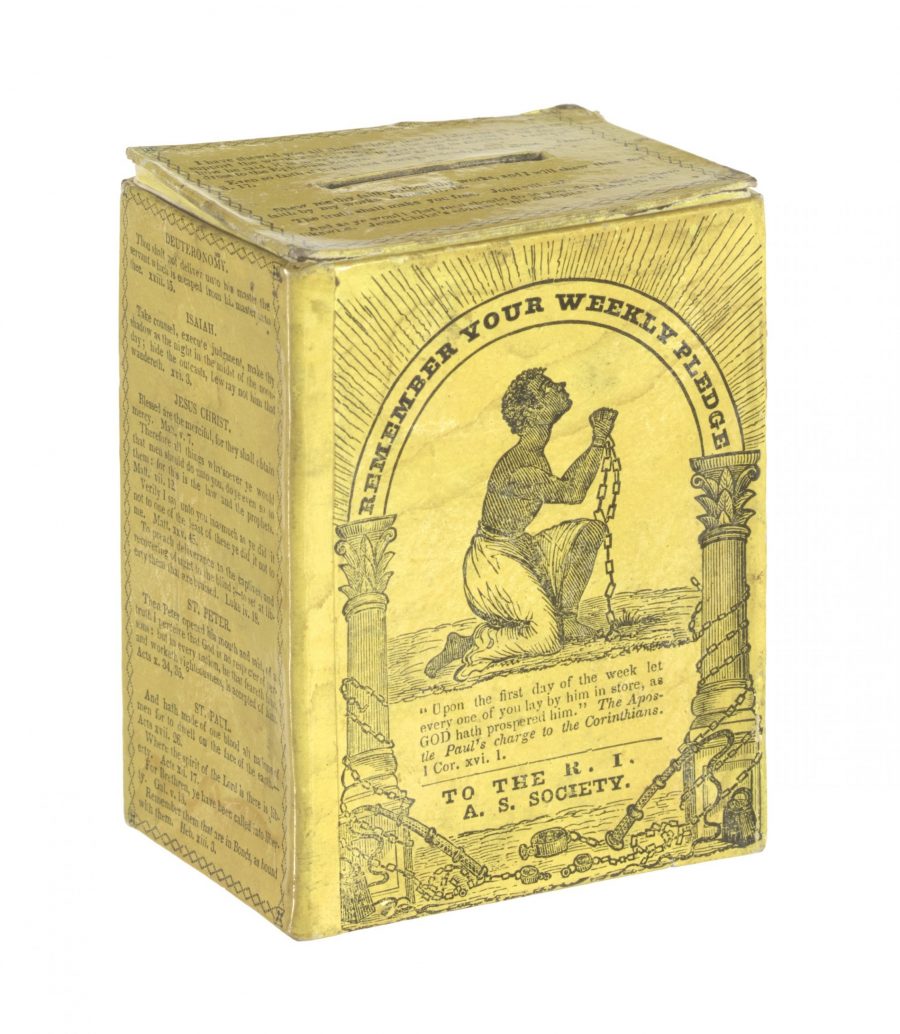

And now—as if that weren’t enough to keep us busy learning about, sharing, adapting, and repurposing the past into the future—the Smithsonian has released 2.8 million images into the public domain, making them searchable, shareable, and downloadable through the museum’s Open Access platform.

This huge release of “high resolution two- and three-dimensional images from across its collections,” notes Smithsonian Magazine, “is just the beginning. Throughout the rest of 2020, the Smithsonian will be rolling out another 200,000 or so images, with more to come as the Institution continues to digitize its collection of 155 million items and counting.”

There are those who would say that these images always belonged to the public as the holdings of a publicly-funded institution sometimes called “the nation’s attic.” It’s a fair point, but shouldn’t take away from the excitement of the news. “Smithsonian” as a conveniently singular moniker actually names “19 museums, nine research centers, libraries, archives, and the National Zoo,” an enormous collection of art and historic artifacts.

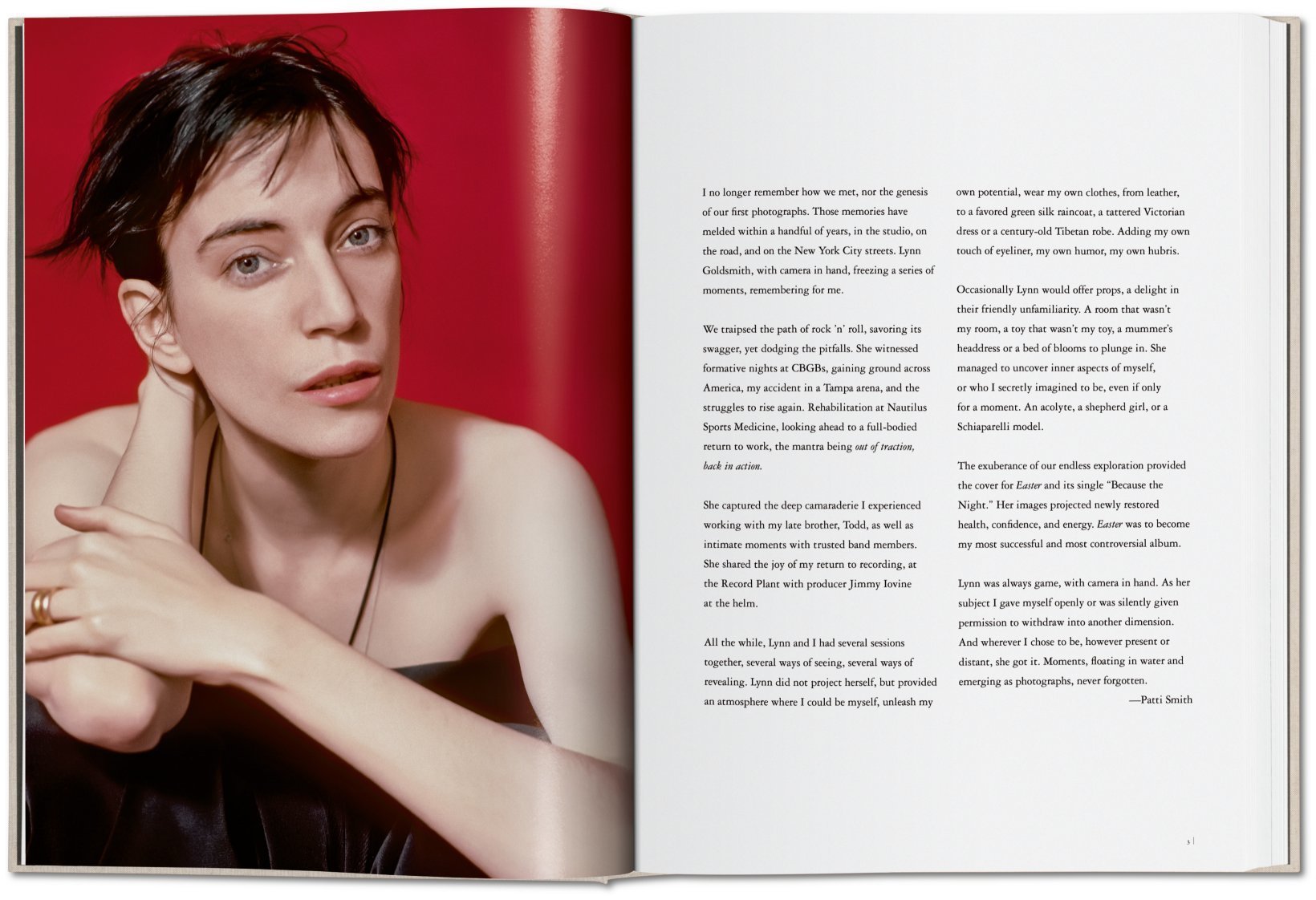

That’s quite a lot to sift through, but if you don’t know what you’re looking for, the site’s highlights will direct you to one fascinating image after another, from Mohammad Ali’s 1973 headgear to the historic Elizabethan portrait of Pocahontas, to the collection box of the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society owned by William Lloyd Garrison’s family, to Walt Whitman in 1891, as photographed by the painter Thomas Eakins, to just about anything else you might imagine.

Enter the Smithsonian’s Open Access archive here and browse and search its millions of newly-public domain images, a massive collection that may help expand the definition of common knowledge.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness