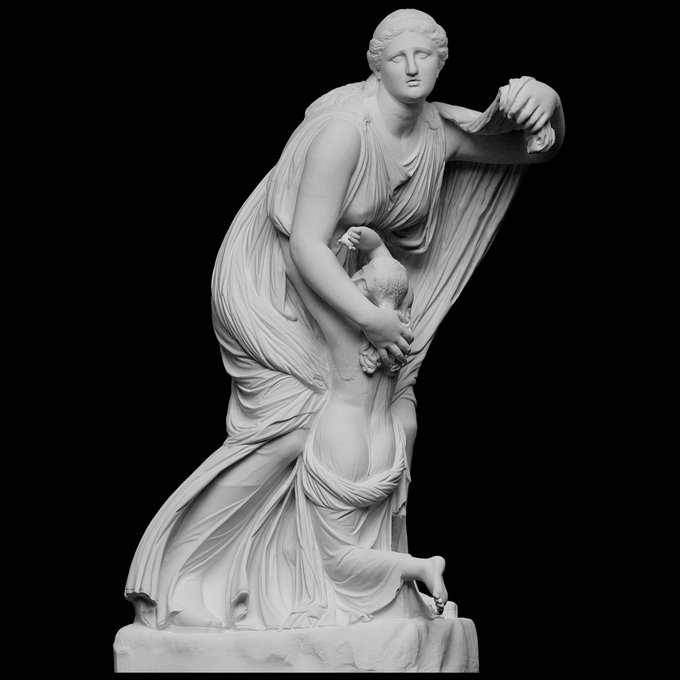

To recent news stories about 3D printed guns, prosthetics, and homes, you can add Scan the World’s push to create “an ecosystem of 3D printable objects of cultural significance.”

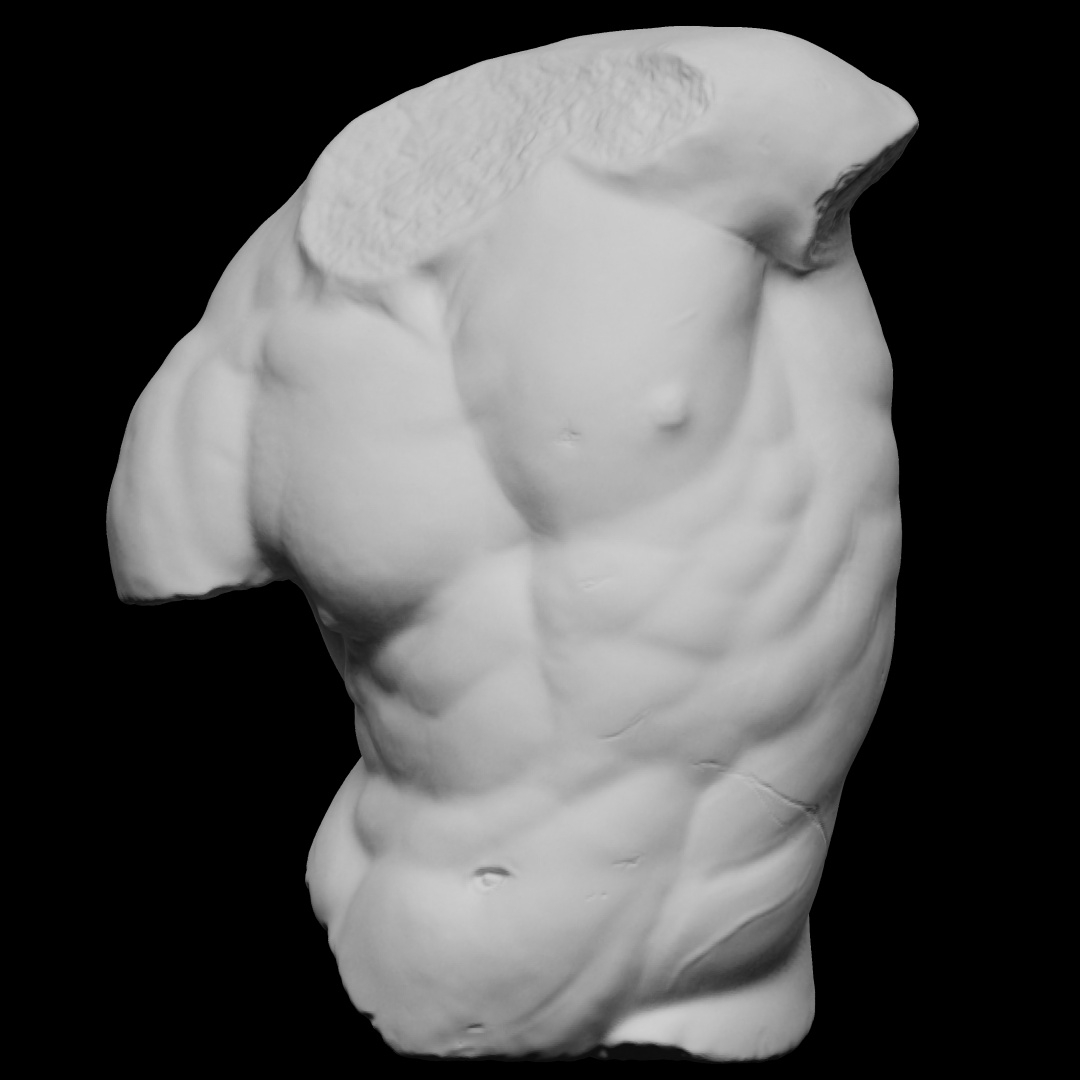

Items that took the ancients untold hours to sculpt from marble and stone can be reproduced in considerably less time, provided you’ve got the technology and the know-how to use it.

Since we last wrote about this free, open source initiative in 2017, Scan the World has added Google Arts and Culture to the many cultural institutions with whom it partners, expanding both its audience and the audience of the museums who allow items in their collections to be scanned prior to 3D printing.

Community contributors have uploaded scan data for over 18,000 sculptures and artifacts onto the platform.

China and India are actively courting participants to make some of their treasures available.

Although Scan the World is searchable by collection, artist, and location, with so many options, the community blog is a great place to start.

Here you will find helpful tips for beginners hoping to produce realistic looking skulls and sculptures — control your temperature, shake your resin, and learn from your mistakes.

Got an unreachable object you’re itching to print? Take a look at the drone photogrammetry tutorial to prep yourself for taking a good scan — rotate slowly, remember the importance of light, and get up to speed on your drone by test-driving it in an open location.

Keep an eye peeled for competitions, like this one, which was won by a photo editor and retoucher with no formal 3‑D training.

Art lovers with little inclination to crack out the 3D printer will find interesting essays on such topics as the Gates of Hell, scanning in the pandemic, and the history of hairstyles in sculpture

You can also embark on a virtual tour of some of the global locations whose splendors are being scanned, programmed, and rendered in resin.

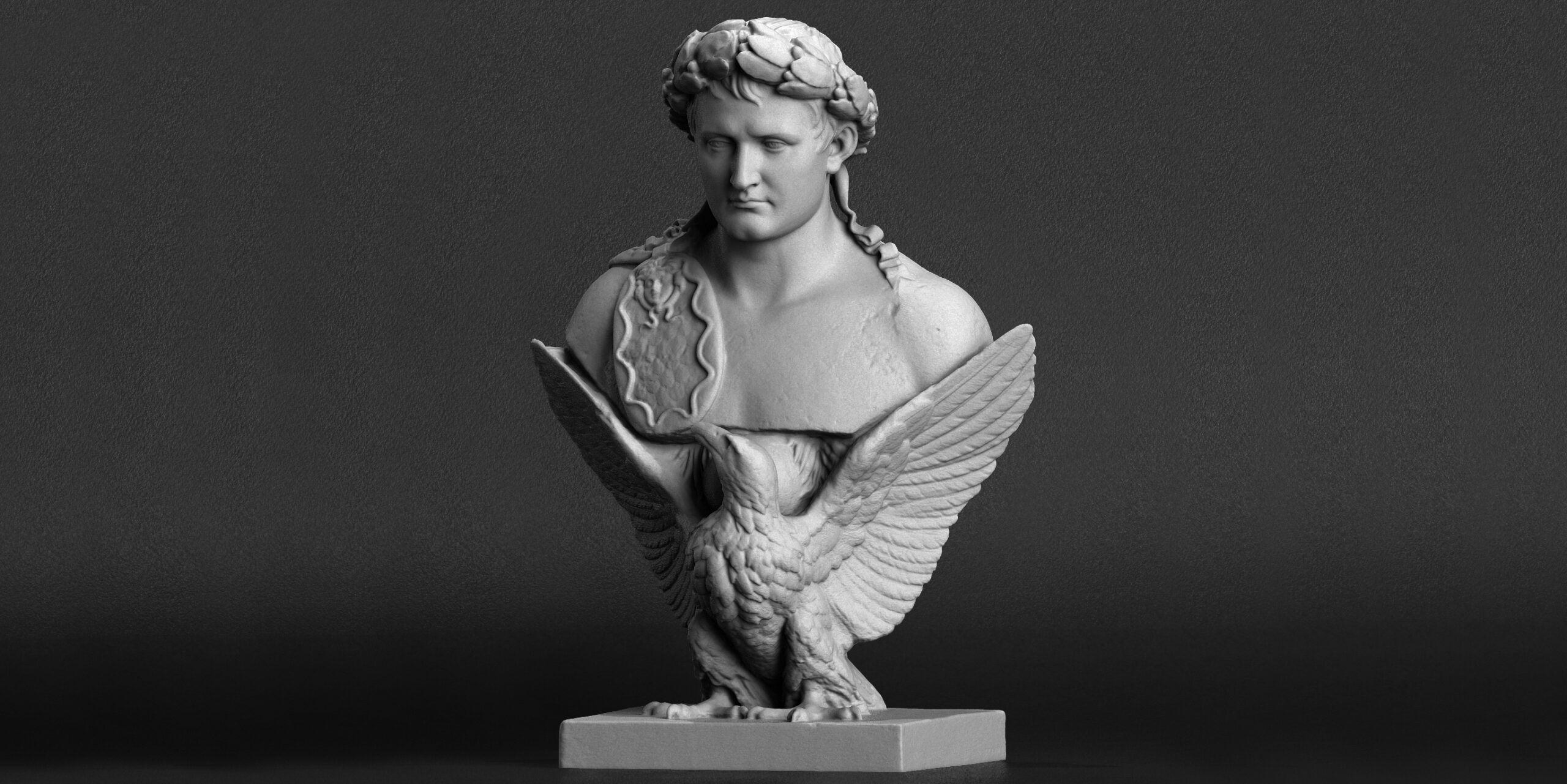

A virtual trip to Paris takes in some of the Louvre’s greatest 3‑dimensional hits: the Venus de Milo, Winged Victory, and Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss.

(Any one of those oughta class up the ol’ bedsit…)

The virtual trip to Austria includes Kierling’s monument to Franz Kafka, the Beethoven memorial in Vienna’s Heiligenstädter Park, and Klaus Weber’s tribute to Hugo Rheinhold’s Darwinian sculpture, Monkey with Skull. (1,868 downloads and counting!)

A Google map awaits those who would tour the original flavor inspirations in person.

Begin your explorations of Scan the World here, and do let us know in the comments if you have plans for printing.

Related Content:

The Earth Archive Will 3D-Scan the Entire World & Create an “Open-Source” Record of Our Planet

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker, Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine, and sometimes, a French Canadian bear known as L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.