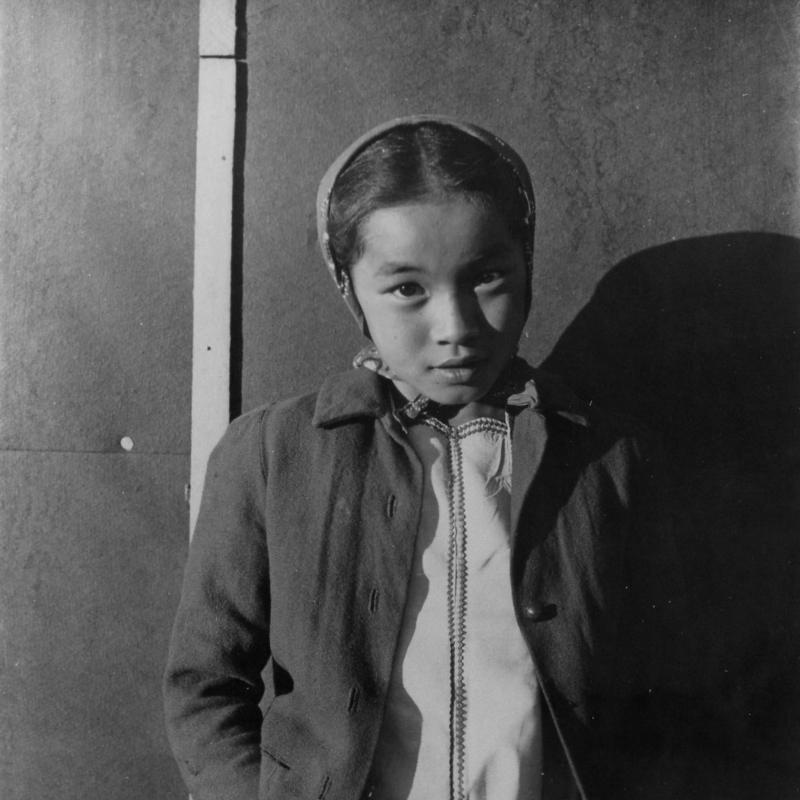

Image by Ansel Adams

In places where atrocities or widespread human rights violations occur, we sometimes hear ordinary citizens later claim they didn’t know what was going on. In the case of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, this would be almost impossible to believe. “120,000 people,” notes Newsweek, “lost their property and their freedom,” rounded up in full view of their neighbors. Every major publication of the time reported on Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 Executive Order. Newsweek wrote “that people in coastal areas ‘were more anxious than ever to get rid of their aliens after rumors that signal lights were seen before submarine attacks’ ” off the coast of Southern California. There were many such rumors, the kind that spread xenophobic fear and paranoia, and which people used to vocally support, or tacitly approve of, sending their neighbors to internment camps because of their ancestry.

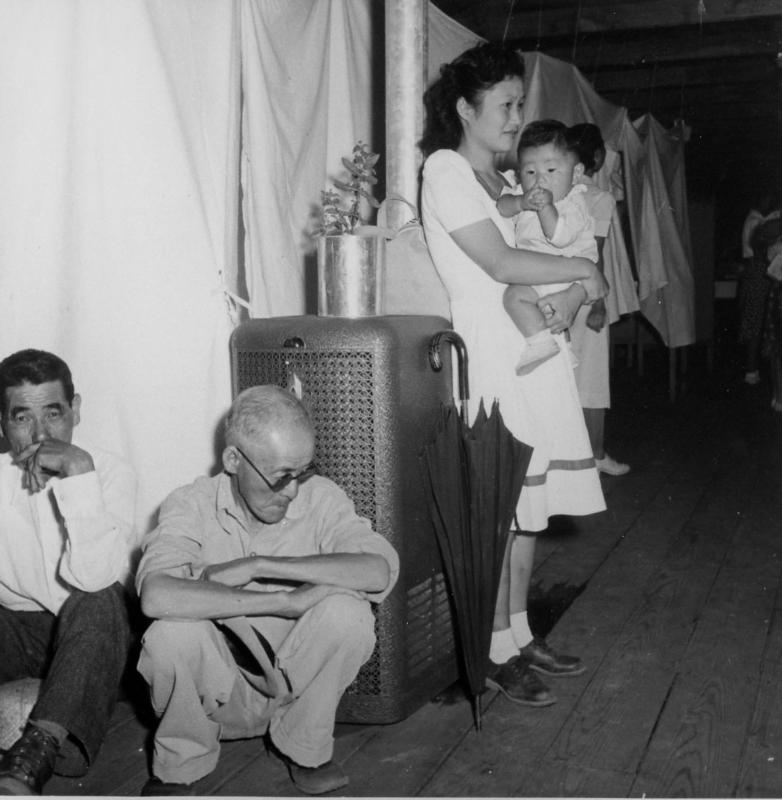

Image by Francis Stewart

Other reactions were less than subtle. The West Seattle Herald confronted readers with the blunt headline “GET ‘EM OUT!” Nonetheless, Newsweek’s Rob Verger writes, “the policy was by no means greeted with unanimous support,” and a vigorous public debate played out, with opponents pointing to the blatant racism and violations of civil rights. Two-thirds of the internees were American citizens. Yet all Japanese Americans were repeatedly called “aliens,” language consistent with the virulently anti-Japanese propaganda campaigns emerging at the same time.

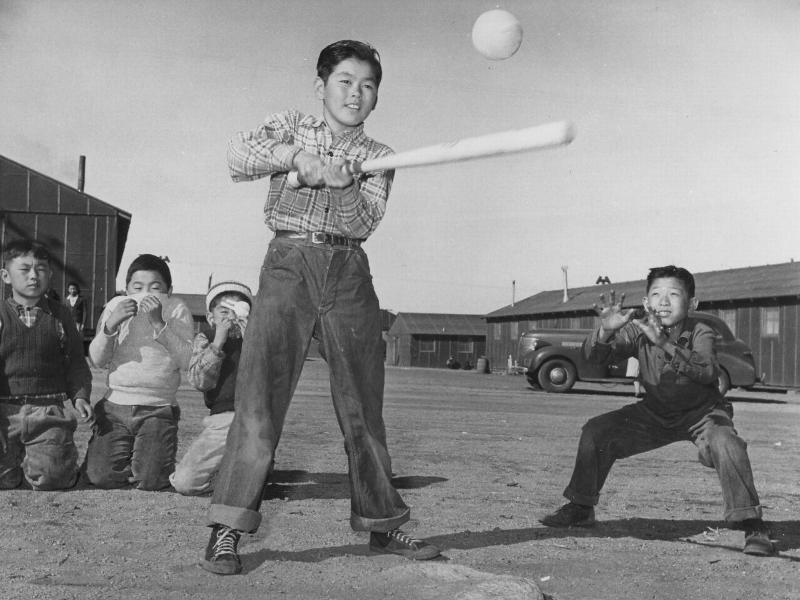

Once the camps were built and the internees imprisoned, however, a massive propaganda effort began, not only the sell the camps as a necessary national security measure, but to portray them as idyllic villages where the patriotic internees patiently waited out the war by farming, playing baseball, making arts and crafts, running general stores, attending school, waving flags, and running newspapers.

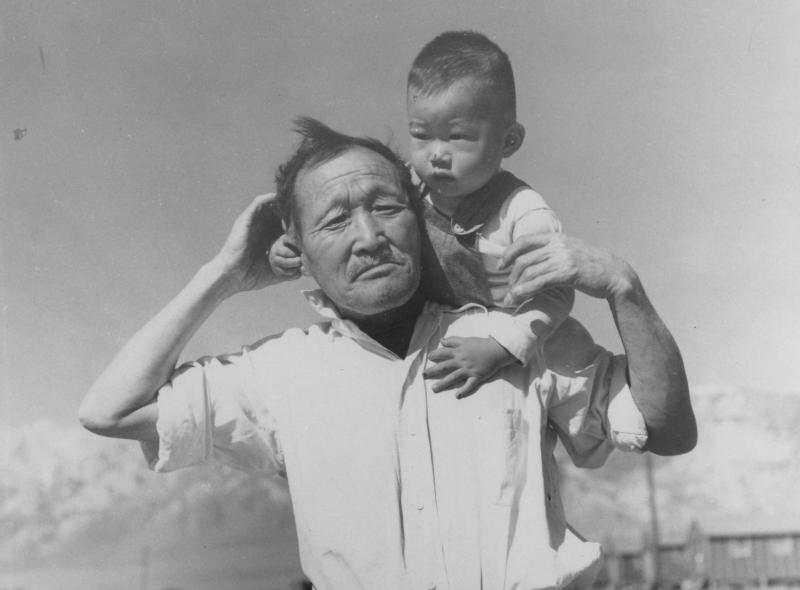

Image by Clem Albers

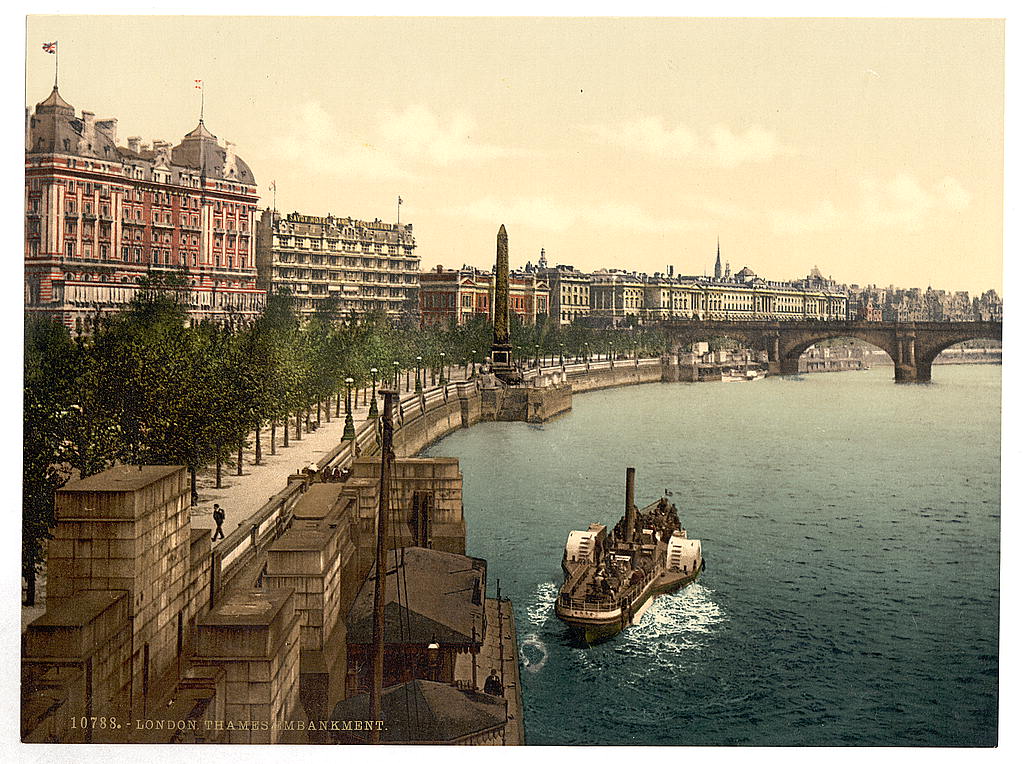

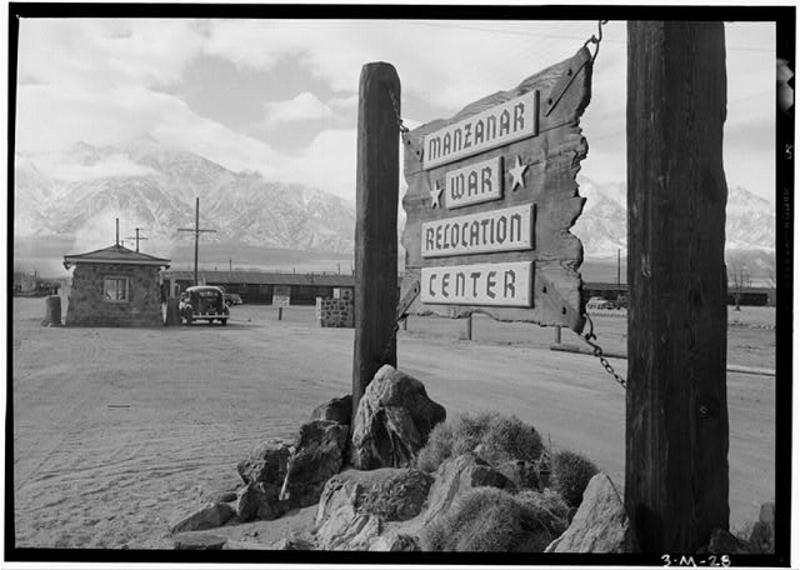

Much of that information was conveyed to the public visually by photographers hired by the War Relocation Authority to document the camps. Among them were Clem Albers, Francis Stewart, and Dorothea Lange—well known for her photographs of the Great Depression. All three visited the camp called Manzanar in the foothills of the Sierra mountains. Another famous photographer, Ansel Adams, gained access to Manzanar by virtue of his friendship with its director, Ralph Merritt.

Image by Dorothea Lange

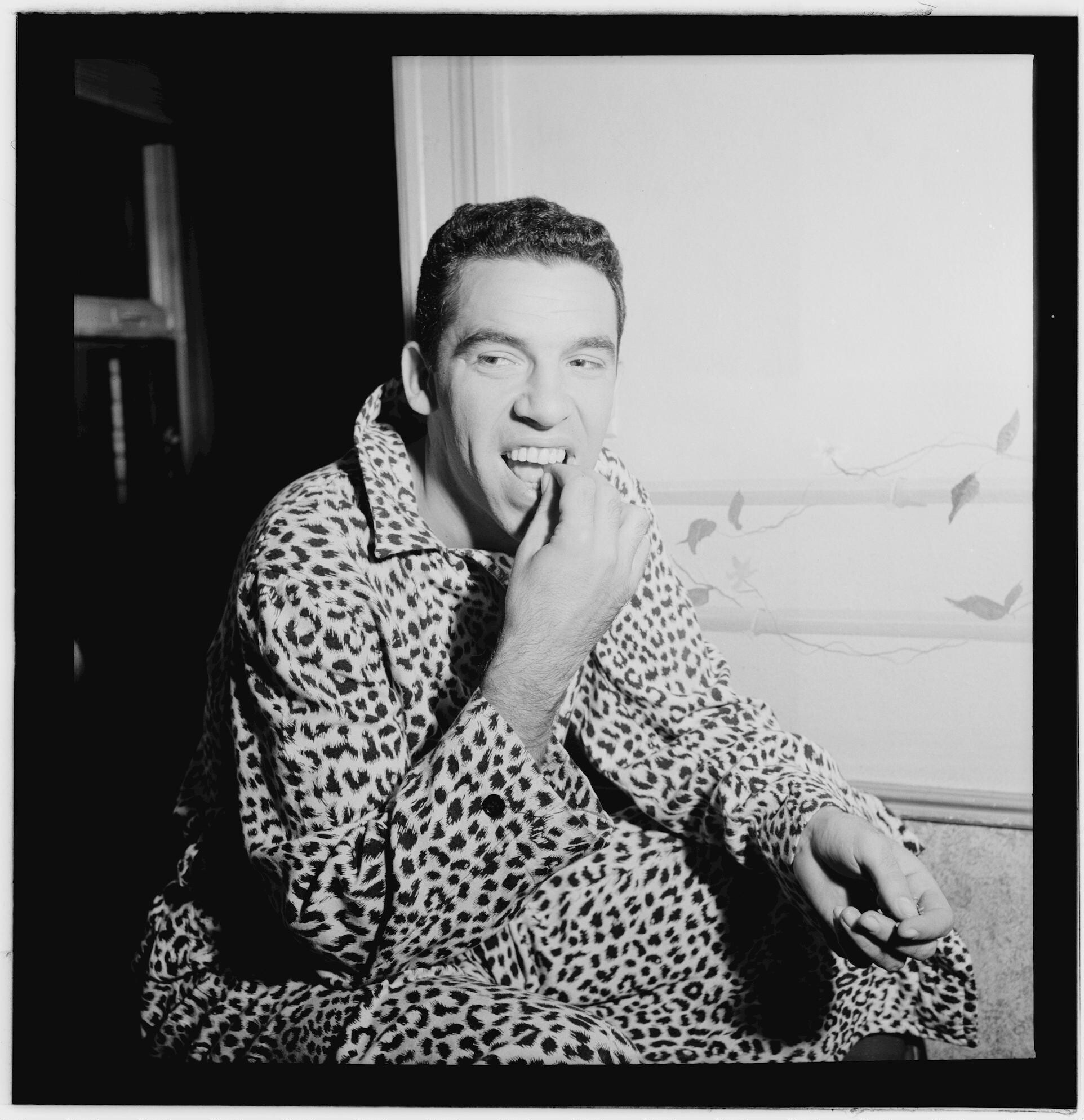

Their photographs, for the most part, show busily working men and women, smiling schoolchildren, and lots of patriotic leisure activities, like Stewart’s photo of sixth grade boys playing softball, further up. The photographers were strictly prohibited from photographing guards, watchtowers, searchlights, or barbed wire, and the heavy military presence at the camp is nearly always out of frame, with some very rare exceptions, like Albers’ photograph above of military police.

Image by Ansel Adams

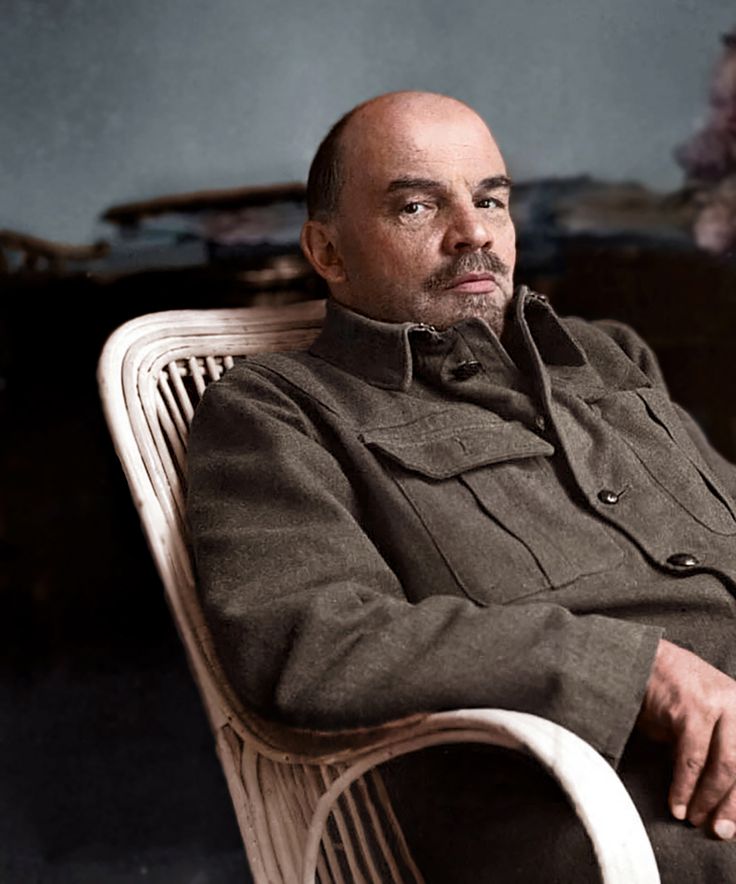

Adams worked under these prohibitions as well, but his photos captured camp life as honestly as he could. The stunning landscapes sometimes compete, even in the background, with the real subject of some of his images (as in the photo at the top). But he also conveyed the harsh barrenness of the region. He tried to intimate the oppressive police apparatus by capturing its shadow. “The purpose of my work,” he wrote to the Library of Congress in 1965 upon donating his collection, “was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, business and professions, had overcome a sense of defeat and despair [sic].” His images often show internees “in heroic poses,” writes Dinitia Smith, as above, in order to ennoble their conditions. Lange’s photographs, on the other hand, like that of a young girl below, “seemingly unstaged and unlighted… bear the hallmarks” of her “distinctively documentary style.” Her pictures “compress intense human emotion into carefully composed frames.” Some of her photos show smiling, relaxed subjects. Many others, like the photograph of a barracks interior further down, show the faces of weary, uncertain, and despondent civilian prisoners of war.

Image by Dorothea Lange

Perhaps because of her refusal to sentimentalize the camps, or because of her left-wing politics and opposition to internment (both known before she was hired), Lange’s work was censored, not only through restricted access, but through the impoundment of over 800 photographs she took at 21 locations. Those photos were recently published in a book called Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment and hundreds of them are free to view online at the Densho Digital Repository’s Dorothea Lange Collection. The National Park Service’s collection features 16 pictures from Lange’s visit to Manzanar. At the NPS site, you’ll also find collections of photographs from that camp by Adams, Albers, and Stewart. Each, to one degree or another, faced a form of censorship in what they could photograph or whether their work would be shown at all. What most ordinary people saw at the time did not tell the whole story. For all practical purposes, writes Oberlin Library, “life at a Japanese internment camp was comparable to the life of a prisoner behind bars.”

Image by Dorothea Lange

Related Content:

478 Dorothea Lange Photographs Poignantly Document the Internment of the Japanese During WWII

200 Ansel Adams Photographs Expose the Rigors of Life in Japanese Internment Camps During WW II

Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who!

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

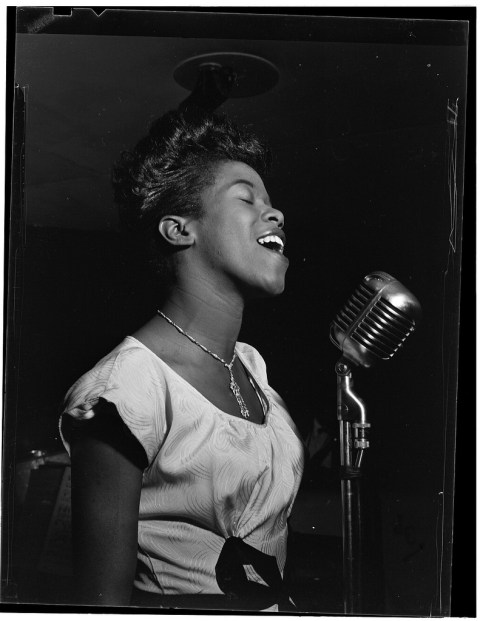

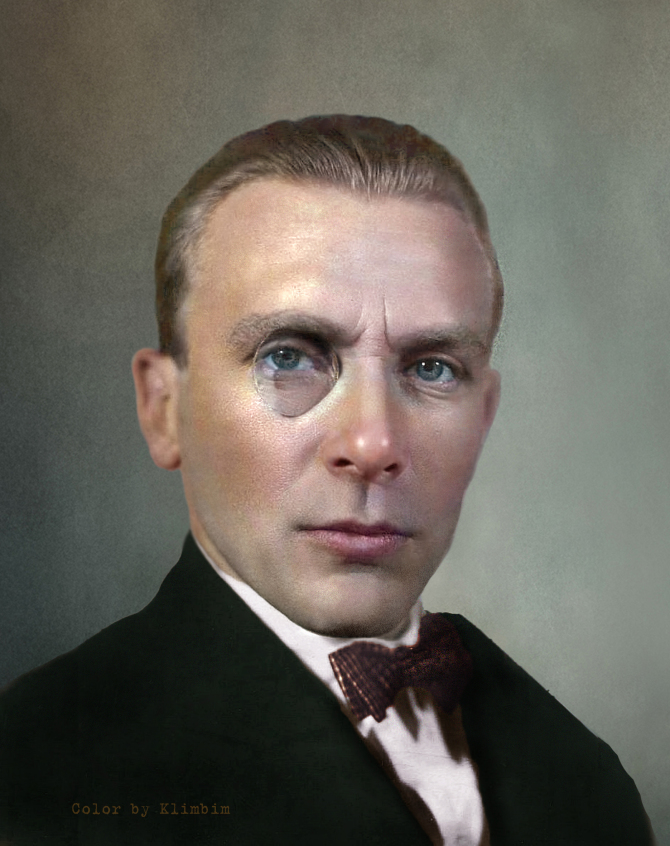

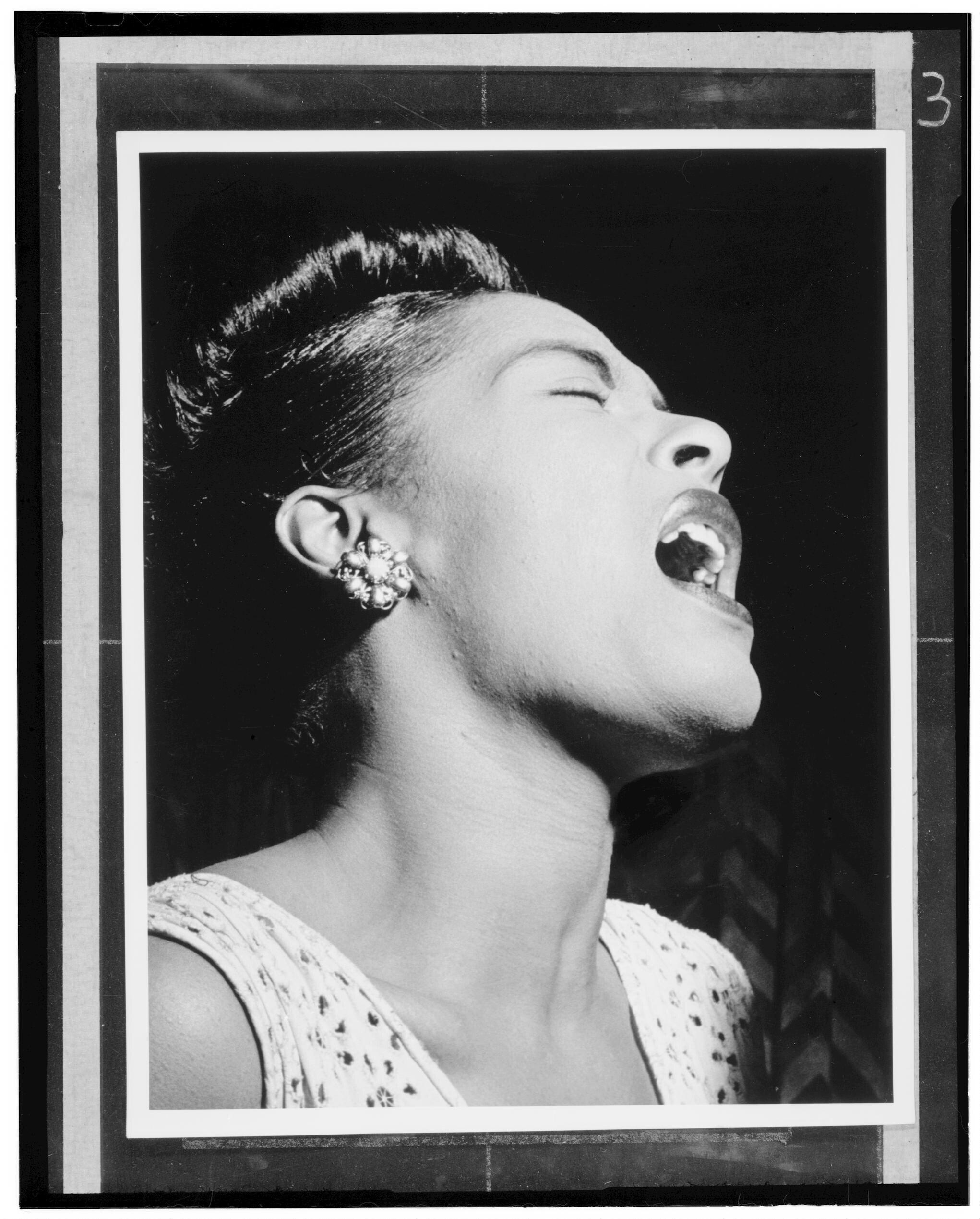

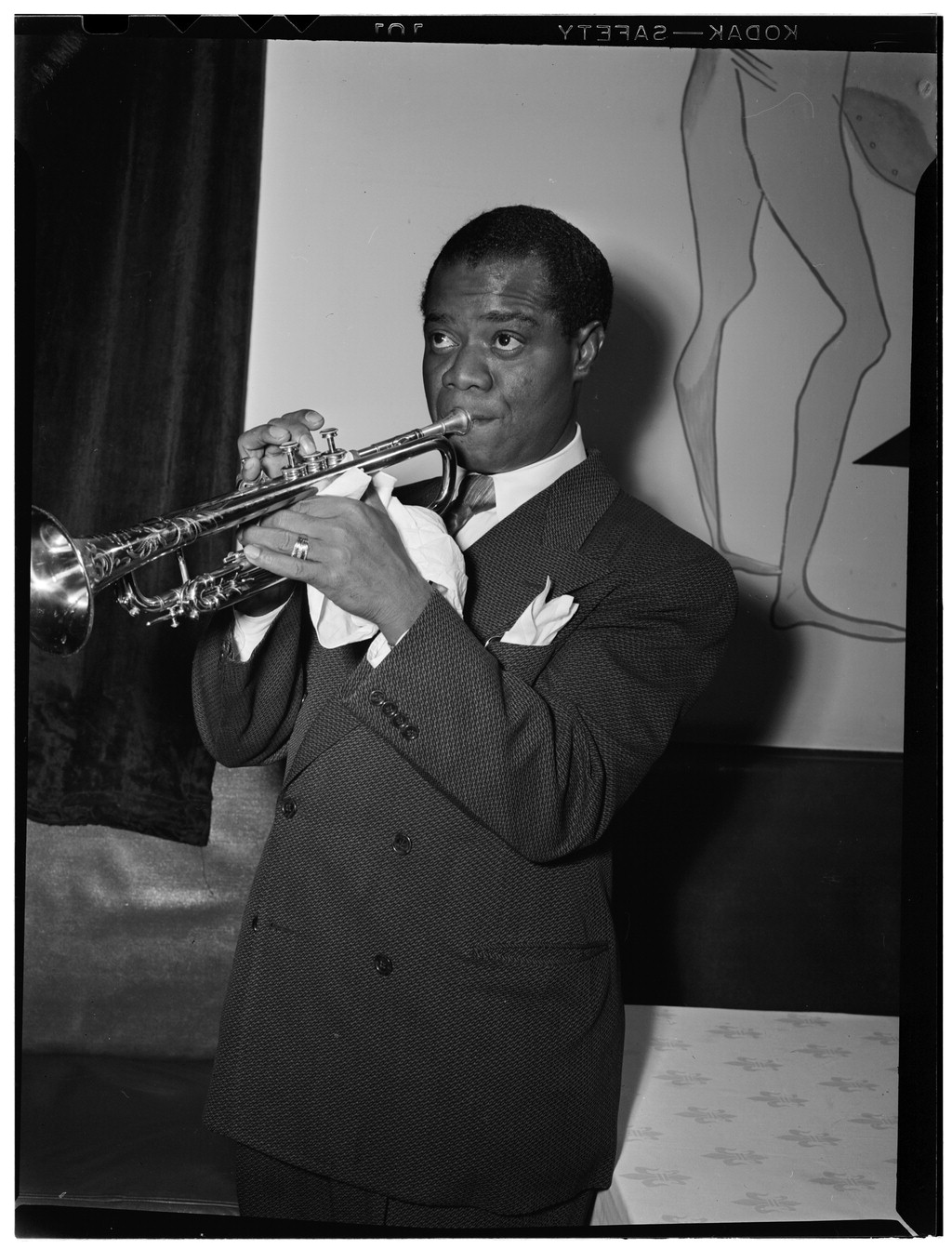

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.