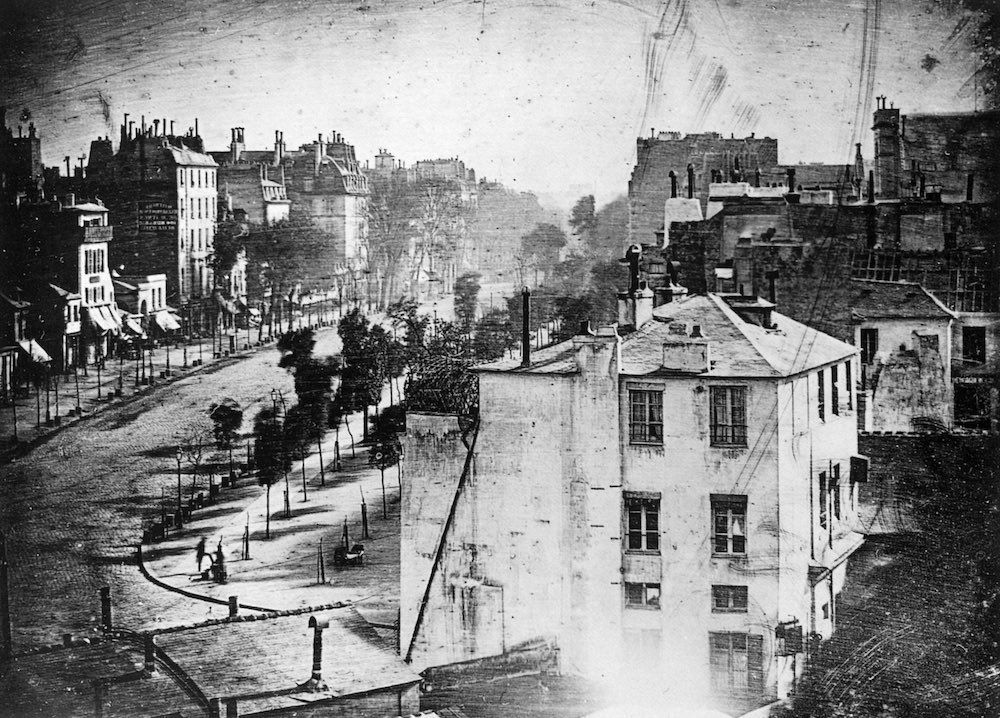

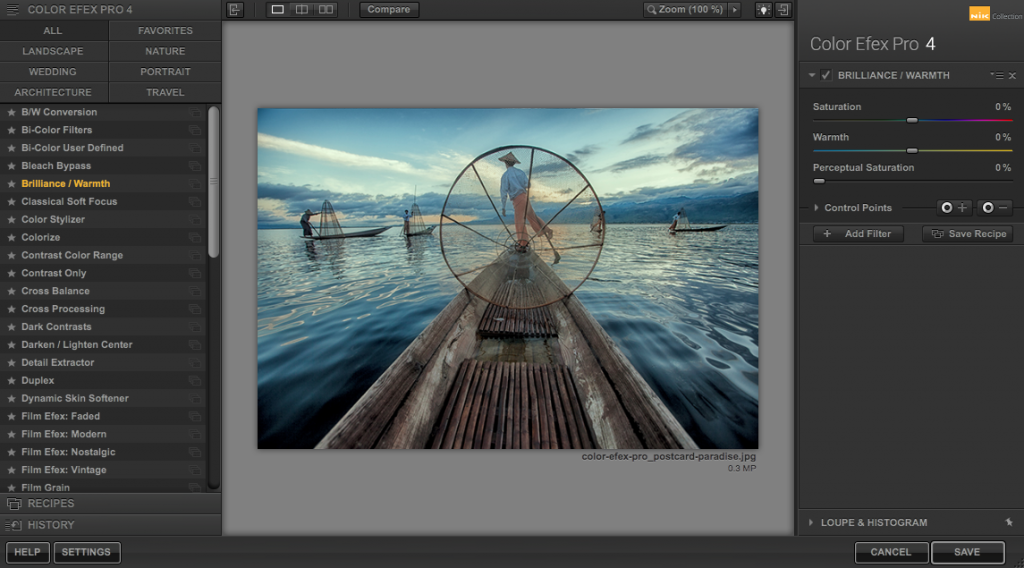

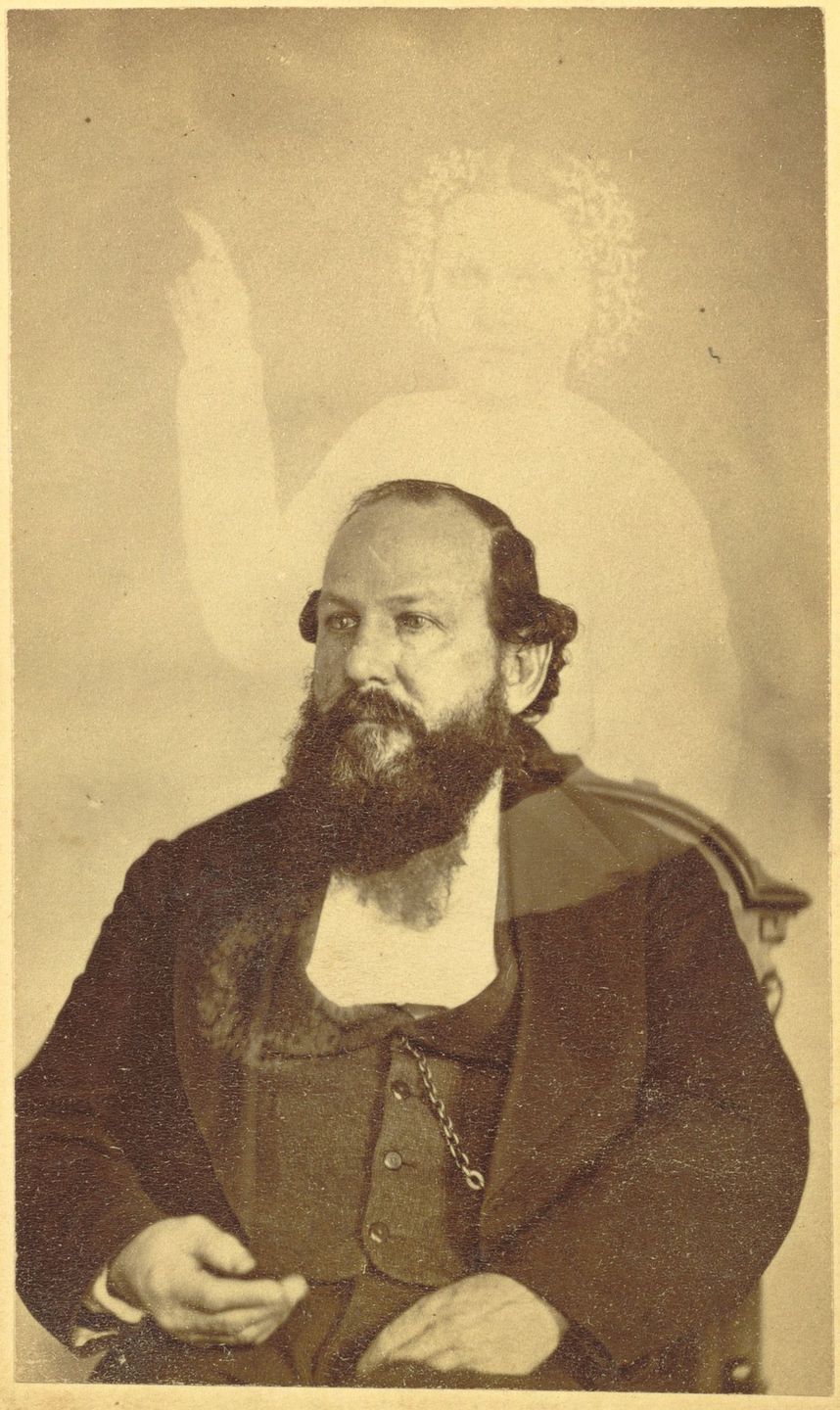

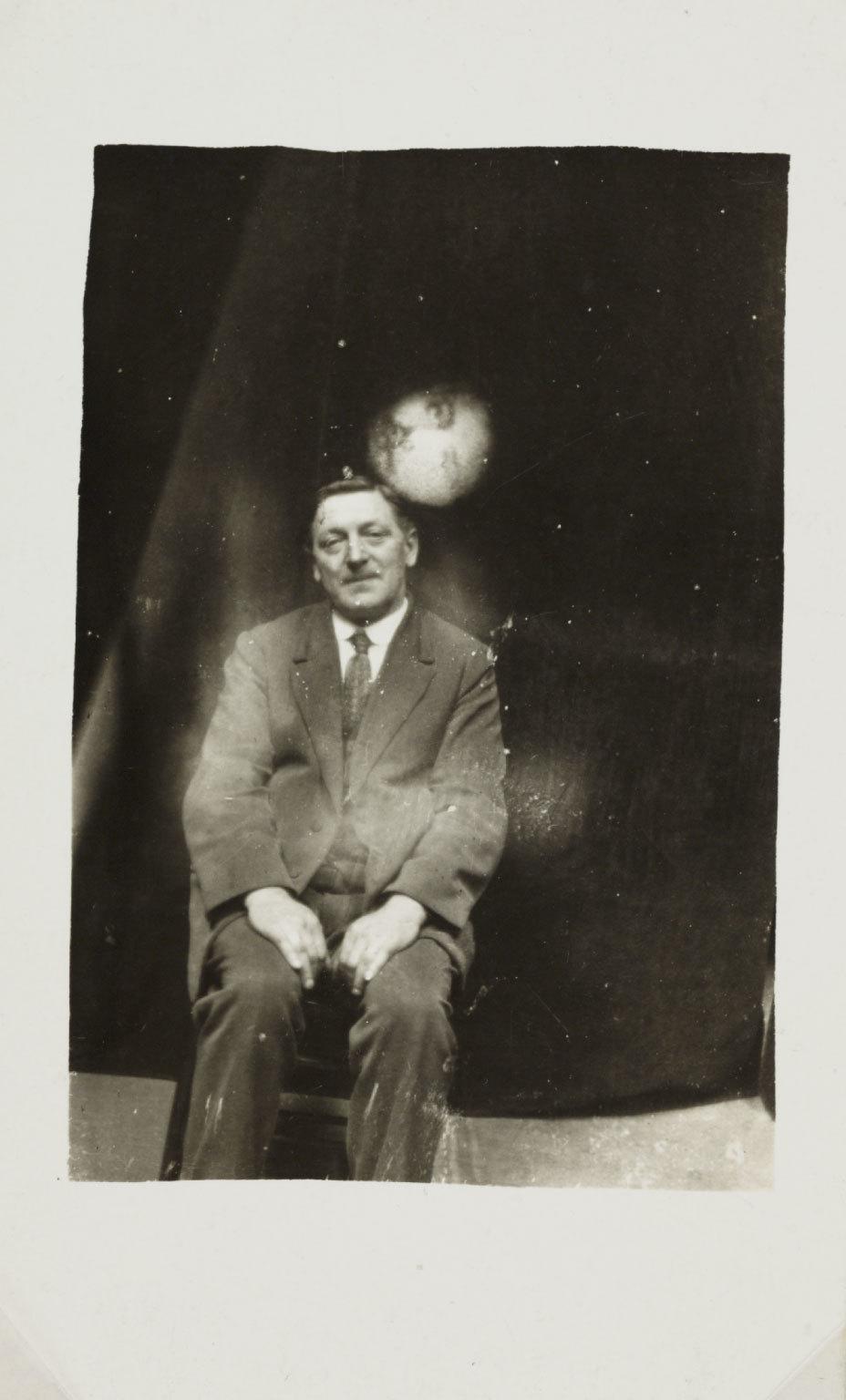

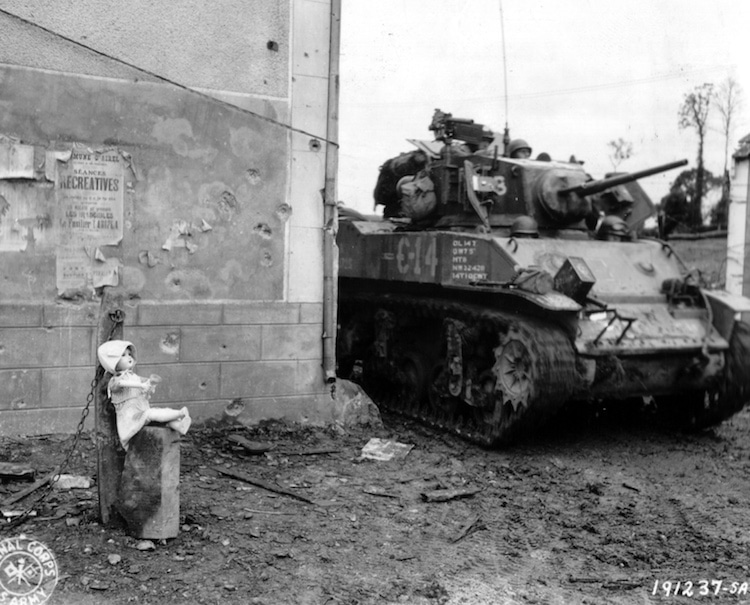

Image above and below by Carl Van Vechten, via Wikimedia Commons

Americans have long considered New York City, at least during its relatively inexpensive eras or in its relatively expensive areas, a haven for every type of artist and members of all subcultures. The density of its population, by American standards, also presents its denizens with the opportunity to cross between one artistic or subcultural realm and another with ease — or with geographical ease, anyway. Few New York figures crossed as many such boundaries as creatively in the early 20th century as a Cedar Rapids-born writer and photographer named Carl van Vechten.

“When Van Vechten first arrived in New York, in 1906, there were few signs that he would ever attempt to appoint himself bard of Harlem,” writes Kelefa Sanneh in a New Yorker piece on Van Vechten’s life. “He was a self-consciously sophisticated exile from the Midwest, and he was quickly hired by the Times as a music and dance critic.” In addition, to his criticism, “he also published a series of mischievous novels that were notable mainly, one critic observed, for their ‘annoying mannerisms.’ ” (The critic? Probably the author himself.) And the longer Van Vechten lived in New York, “the more interested he became in the sights and sounds of Harlem, where raucous and inventive night clubs were thriving under Prohibition.”

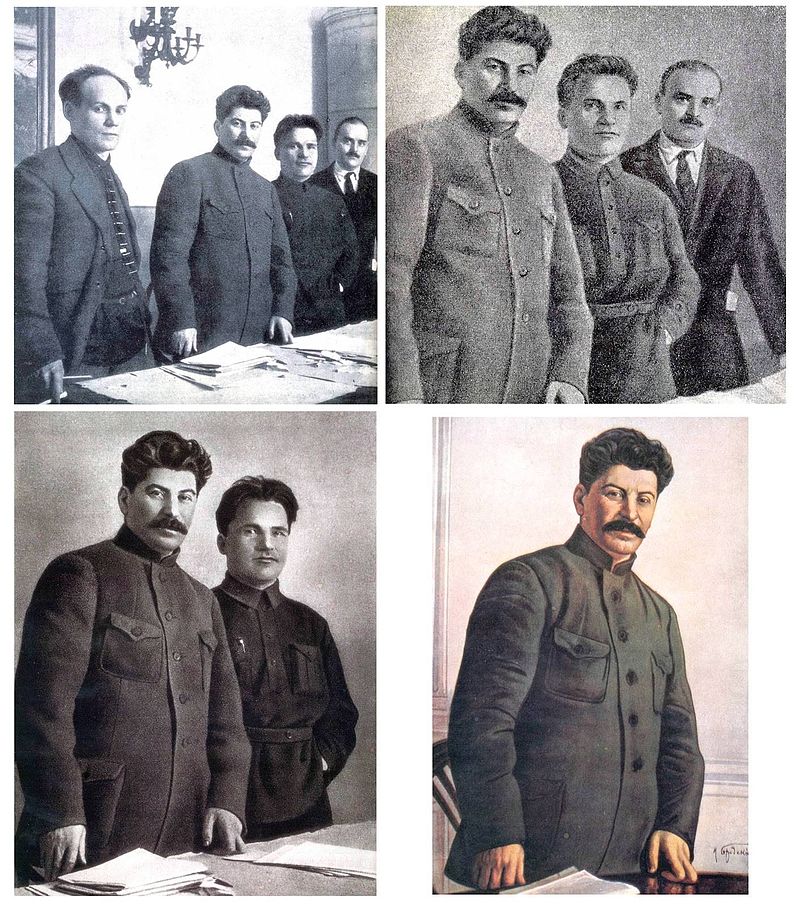

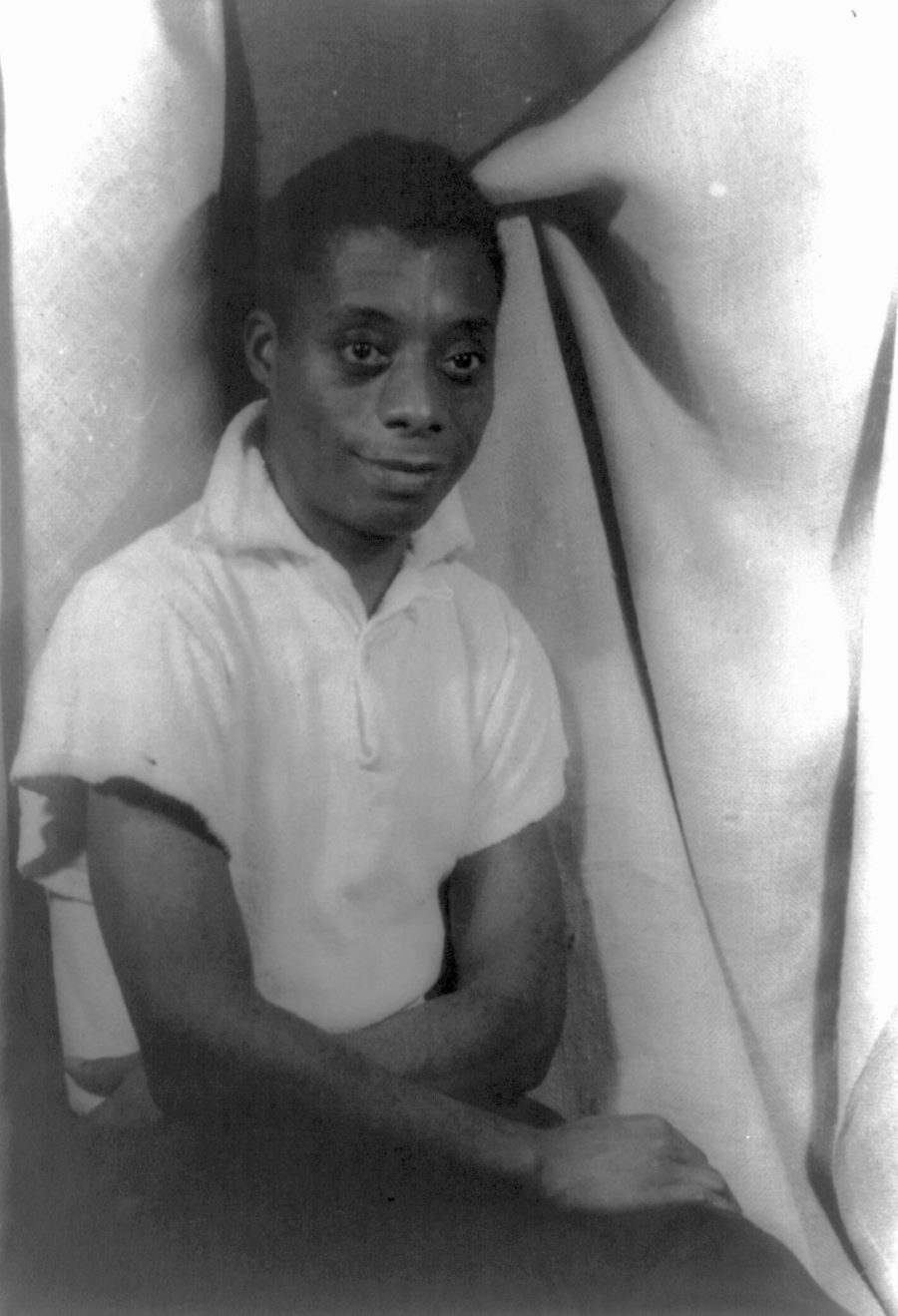

The white Van Vechten wrote a novel about black life in Harlem, insisting on a title that I doubt I can even type here. It expressed what Sanneh calls “his conviction that Negro culture was the essence of America,” which went with “his simultaneous fascination with the avant-garde and the broadly popular; and his string of sexual relationships with men, which were an open secret during his life. Van Vechten’s tastes were varied: his bibliography includes an erudite cultural history of the house cat, and in his later decades he became an accomplished portrait photographer.” Black, white, or otherwise, nearly every major figure in the American culture of the day seems to have sat for his camera: actors, writers, musicians, intellectuals, architects, magnates, and many other types besides.

Some of the subjects of Van Vechten’s over 9,000 portraits, all browsable online at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, were his friends: Gertrude Stein, and Langston Hughes, for instance, both of whom expressed great enthusiasm for Van Vechten’s writing on black culture. Others created that black culture, now known as the Harlem Renaissance: Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holliday, James Baldwin. Others made up the culture of global celebrity, then only in its infancy: Orson Welles, Lotte Leyna, Laurence Olivier.

They, and more so Van Vechten himself, knew that to become an icon in the 20th century, you needed to do much more than excel in the human realm: you had to transcend it, ascending into that of the image. If you sufficiently fascinated Van Vechten, it seems, he was only too glad to help you on your way there. See thousands of his portraits at this Yale website.

Portraits in order of appearance on this page include: Billie Holliday, Orson Welles, James Baldwin, Gertrude Stein, and Dizzy Gillespie. All come courtesy of the Van Vechten Collection at Library of Congress.

Related Content:

A 1932 Illustrated Map of Harlem’s Night Clubs: From the Cotton Club to the Savoy Ballroom

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.