(Image credit: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

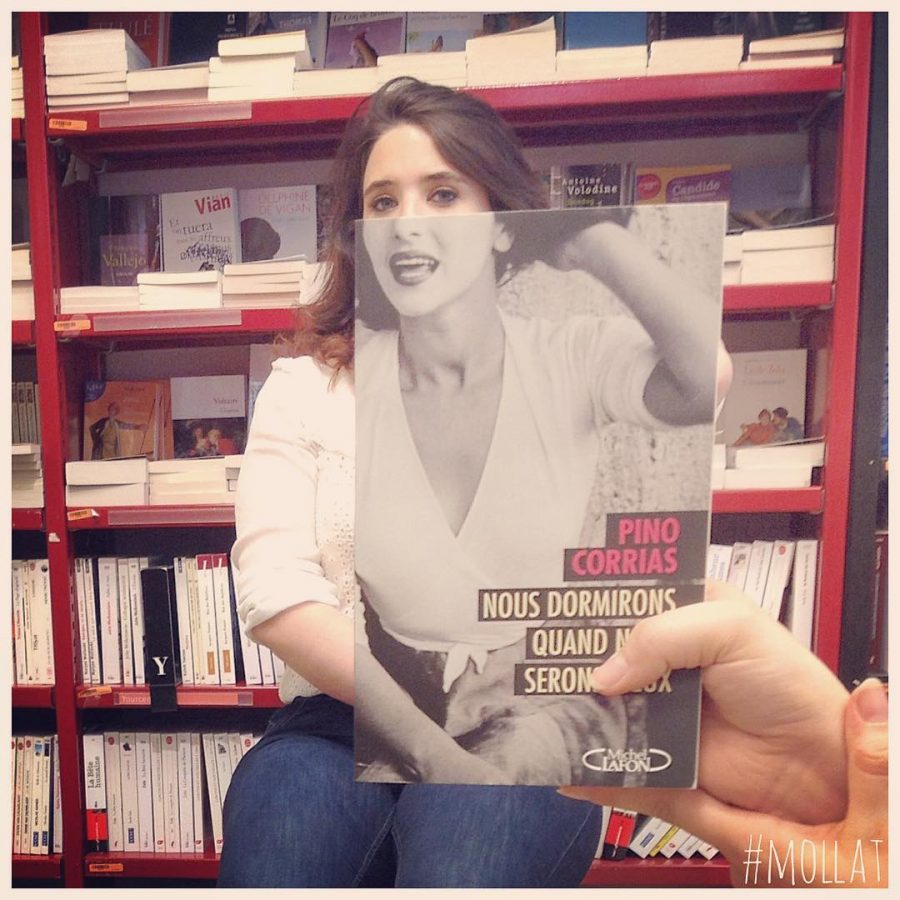

It’s taken for granted that every brand or rising star must establish and maintain a constant presence on various social networks. Indeed, the social media star—an entity famous solely for collecting followers and posting glamorous photos with themed commentary—may seem like a phenomenon that could only exist in the internet age, though writers like J.G. Ballard saw such things coming decades ago.

But before obsessive photography saturated the digital environment, Andy Warhol grasped the medium’s central importance in the documentation of everyday life. It just so happened that his everyday life was filled with celebrity actors, models, artists, and musicians.

Warhol, writes James D. Ellis at Light Stalking, “was the proto-hipster,” a restless moth always on the hunt for a flame. “Much like our contemporary culture, Warhol found it difficult to sit and do nothing. He had to leave his house or Factory and experience his immediate surroundings.”

(Image credit: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

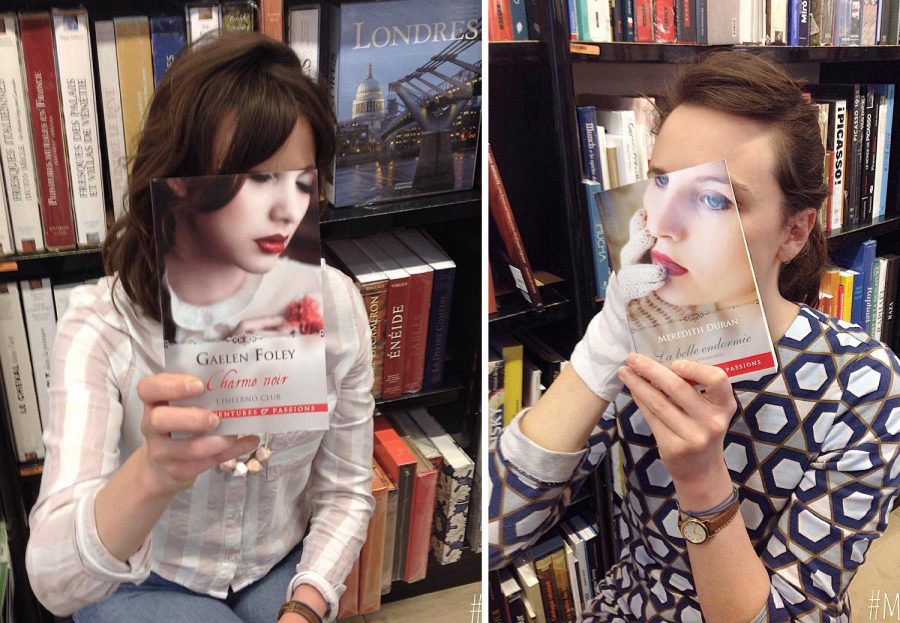

And he had to photograph every one of those experiences. Warhol used his Polaroids and 35mm the way we use iPhones. A court case in the early nineties once took up the question of whether Warhol’s photographs could be considered fine art, but the artist himself, writes Patina Lee at Widewalls, “was obviously undecided about their value and meaning,” saying “A picture means I know where I was every minute. That’s why I take pictures. It’s a visual diary.”

Warhol, Lee writes, “took his camera with him wherever he went, documenting practically everything, the highest high class and the lowest trash (literally, he took photos of trash cans and of what they contained)…. This inclusiveness is what made his photographic undertakings border between art and mere obsessive collecting, or as people like to cynically notice, consuming the life around him.” His consumption, and photographs of trash, comes to us as treasure, an extensive record of Warhol’s New York in the seventies and eighties.

(Image credit: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

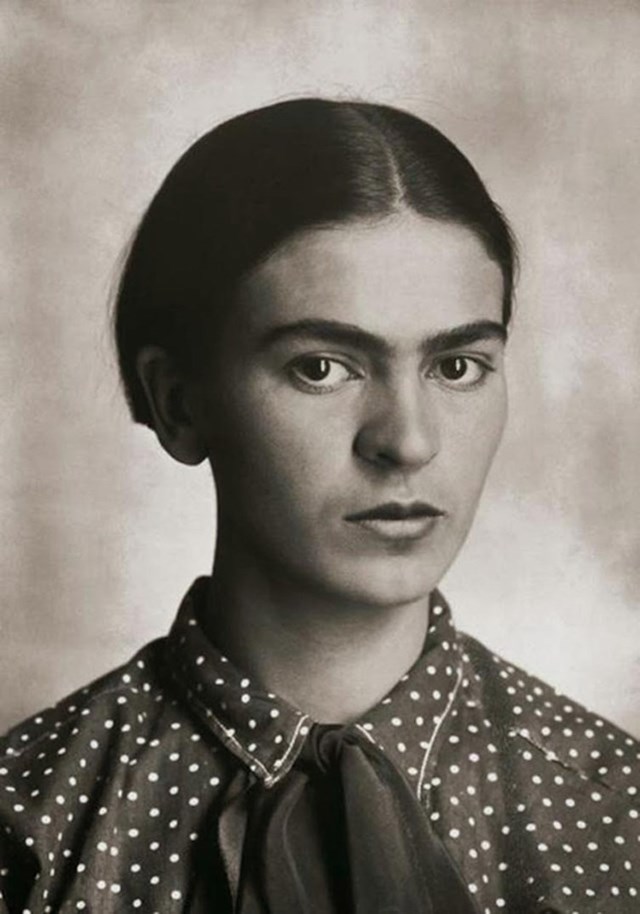

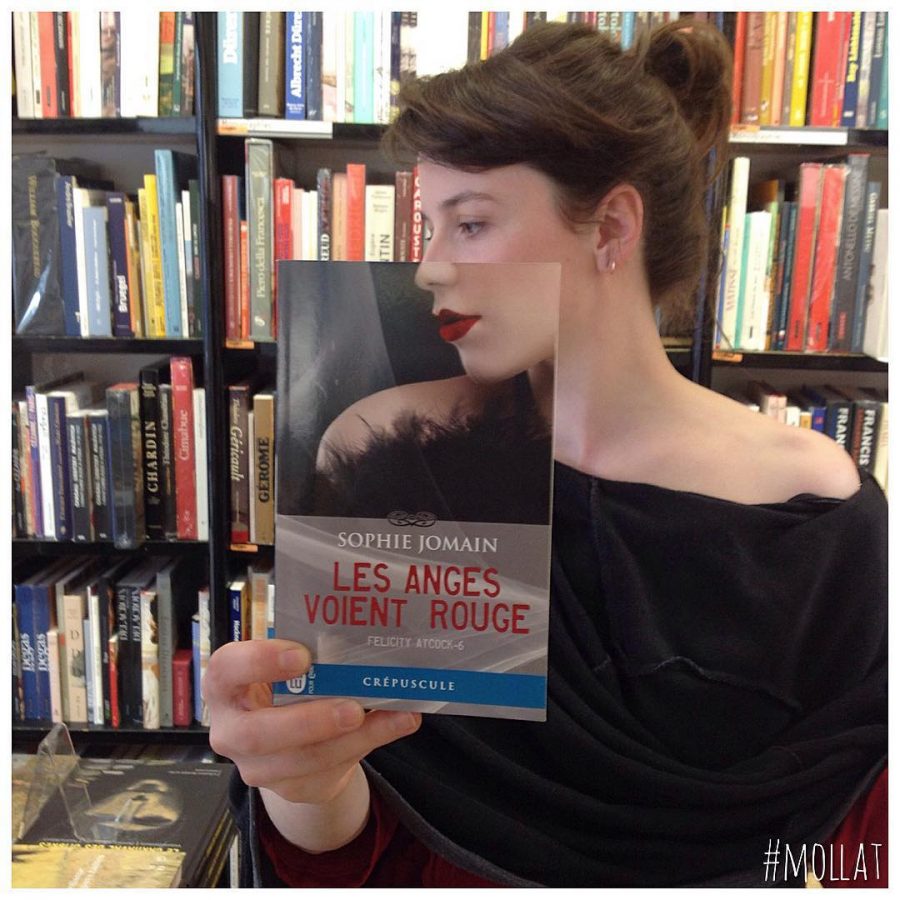

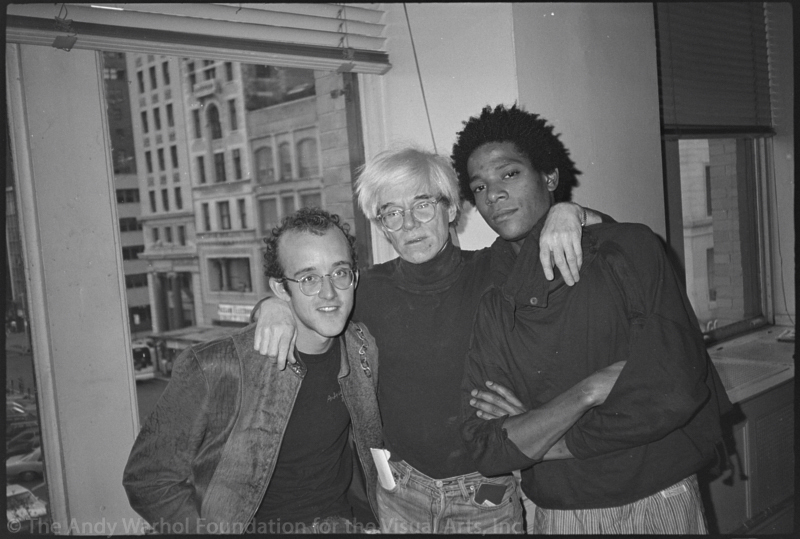

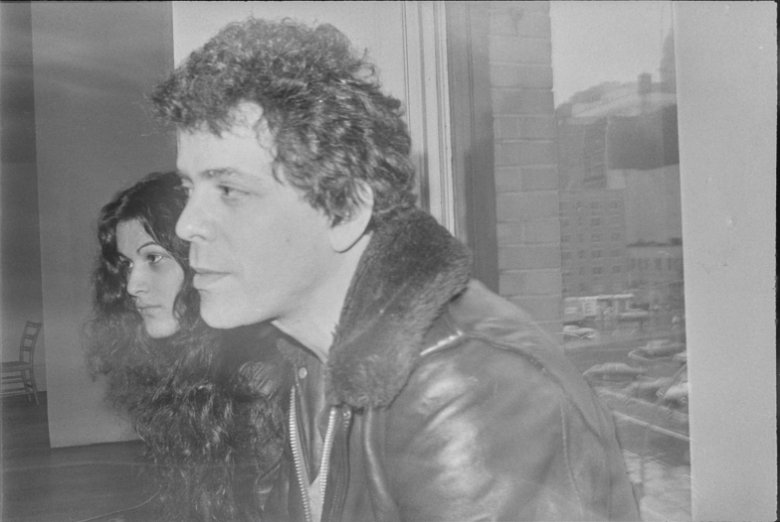

Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center and Stanford Libraries have collaborated to make their Warhol photo archives available to the public—photos snapped “at discos, dinner parties, flea markets, and wrestling matches. Friends, boyfriends, business associates, socialites, celebrities, and passersby.” This “trove of 3,600 contact sheets featuring 130,000 photographic exposures” documents Warhol’s daily life from 1976 until his death in 1987 and includes candid photos of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Truman Capote, Bianca Jagger, Jimmy Carter, Martha Graham, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry, Grace Jones, Jackie Kennedy, Liza Minelli, Dolly Parton, Elizabeth Taylor, and more.

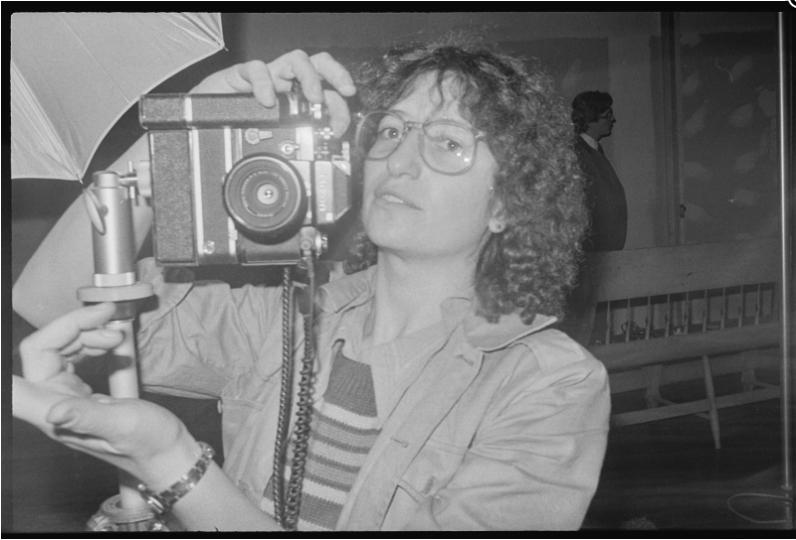

The archive, writes Sandra Feder for Stanford News, “is the most complete collection of the artist’s black-and-white photography ever made available to the public.” It was acquired by the Cantor in 2014 from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Given that these are all contact sheets, navigating the collecting can be a little bewildering. The Cantor has provided a number of tools to help. Click on Contact Sheets here to explore all 3,600+ contact sheets. Click Negatives to see individual frames, like those of Keith Haring, Warhol, and Jean-Michel Basquiat at the top, Lou Reed further up, and Annie Leibovitz above. Or start browsing through pictures organized by theme here.

(Image credit: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

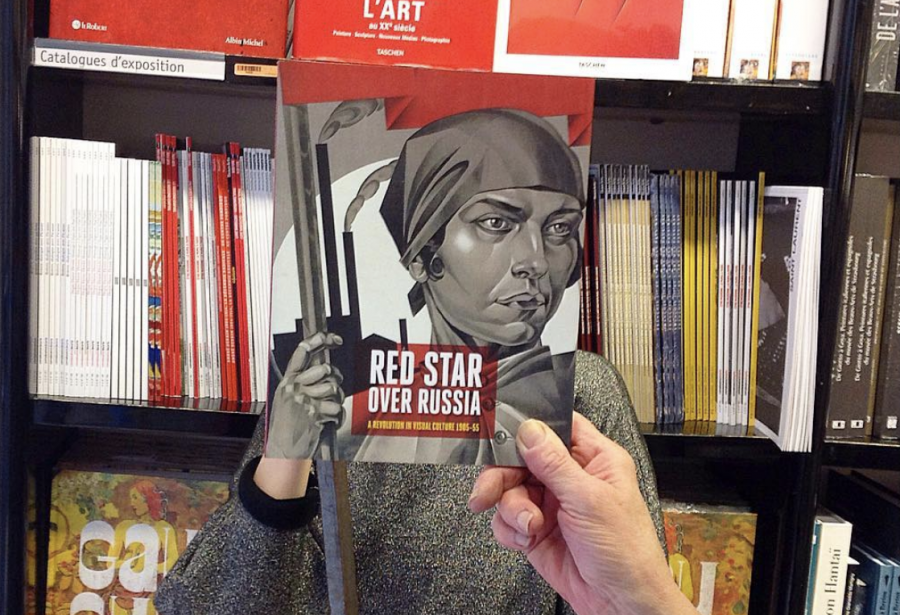

Dig deep, and you’ll find the oddest things, like Andy Warhol running in Central Park for charity with Grace Jones and photographer Gordon Parks. Whatever Andy did, whoever he happened to do it with—and a stranger cast of characters you will not find—it’s all in this huge photo archive somewhere.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The Case for Andy Warhol in Three Minutes

Short Film Takes You Inside the Recovery of Andy Warhol’s Lost Computer Art

Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol Demystify Their Pop Art in Vintage 1966 Film

Watch Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests of Three Female Muses: Nico, Edie Sedgwick & Mary Woronov

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness