J. Paul Getty was not a billionaire known for his generosity. But since his death, the Getty Trust and complex of Getty museums in L.A. have carried forth in a more magnanimous spirit, ostensibly adhering to values that transcend their founder: “service, philanthropy, teaching, and access.”

A collection first gathered for private investment and consumption (sometimes under a cloud of scandal) has expanded into galleries that millions pass through every year; a Conservation Institute dedicated to preserving the world’s art; and a Research Institute proclaiming a social mission: a devotion to expanding “our knowledge of the history of art, of all countries, of all languages,” according to its director Thomas Gaehtgens, who also says, “a society without art cannot really survive.”

Put another way, as one of the Getty’s art market competitors was once quoted as saying, “They just want people to like them.” He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but if you are an art lover—and not a billionaire art collector—you may genuinely appreciate this quality. And you may like them even more now that their open access digital collections have almost doubled to 135,000 high-resolution images since we last checked in with them five years ago.

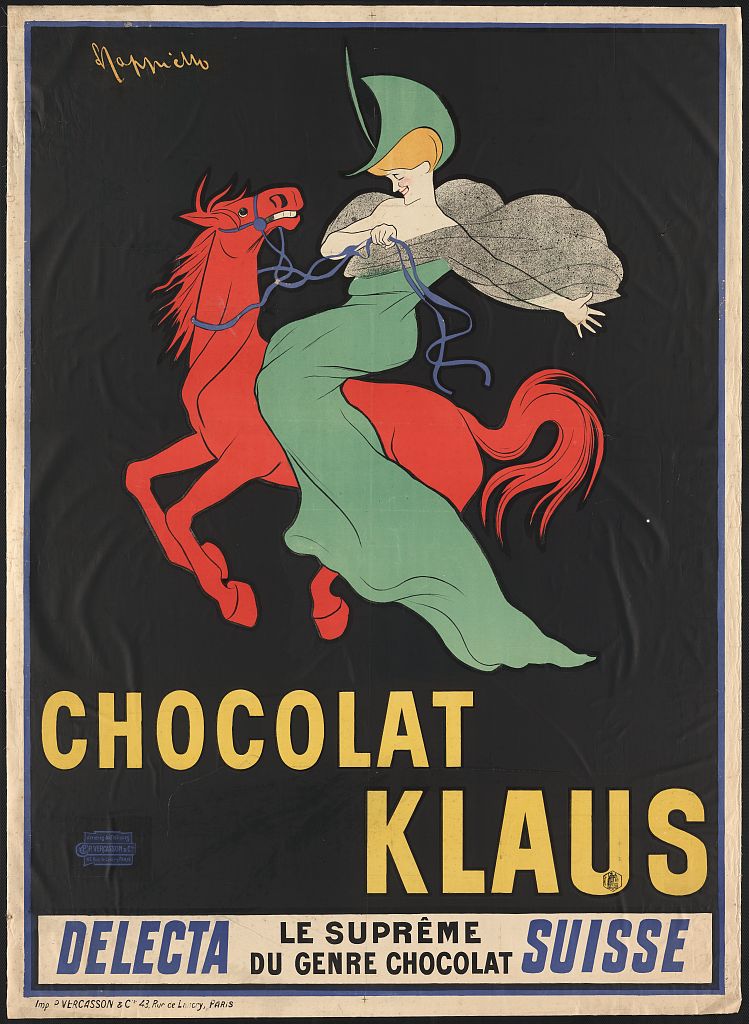

Like the Getty museum, it reflects its founder’s tastes in Classical, Neo-Classical, and Renaissance art. Download Andrea Mantegna’s Adoration of the Magi (top), for example, at the highest resolution (8557 X 6559) and get closer to a virtual version than you ever could to the real thing. Learn the painting’s provenance and exhibition history, read an informative description and a bibliography. The painting is one of hundreds from European masters and their lesser-known apprentices. You’ll also find several hundred images of sculpture, both classical and modern—like Paul Gauguin’s sandalwood Head with Horns, above—as well as drawings, manuscripts, pottery, jewelry, coins, decorative arts, and much more.

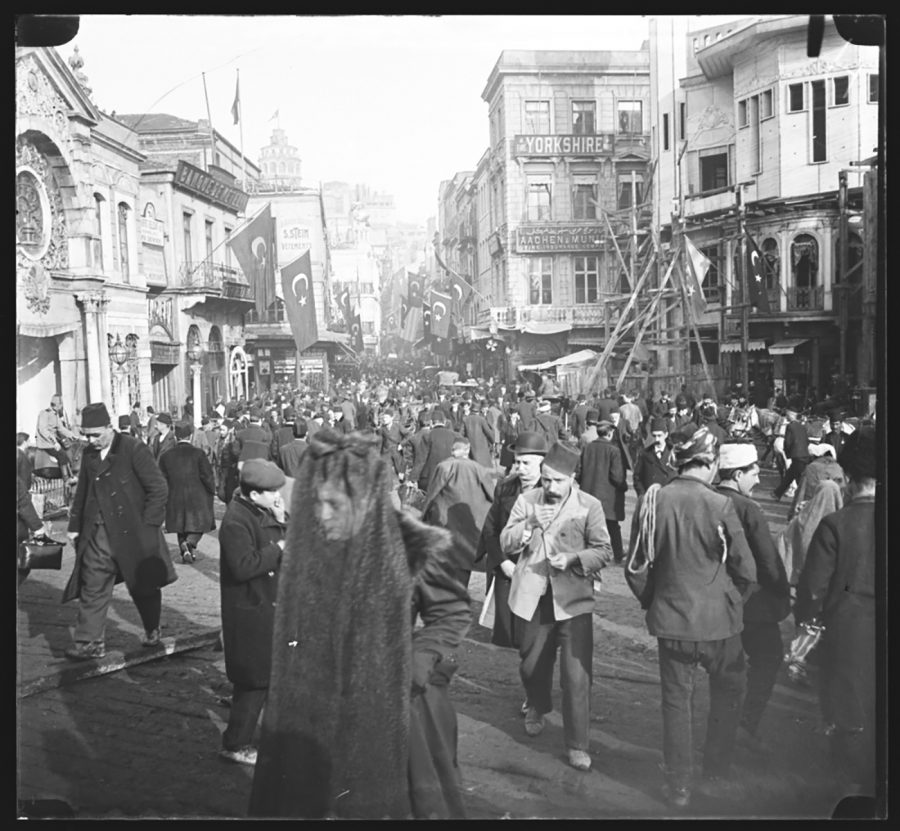

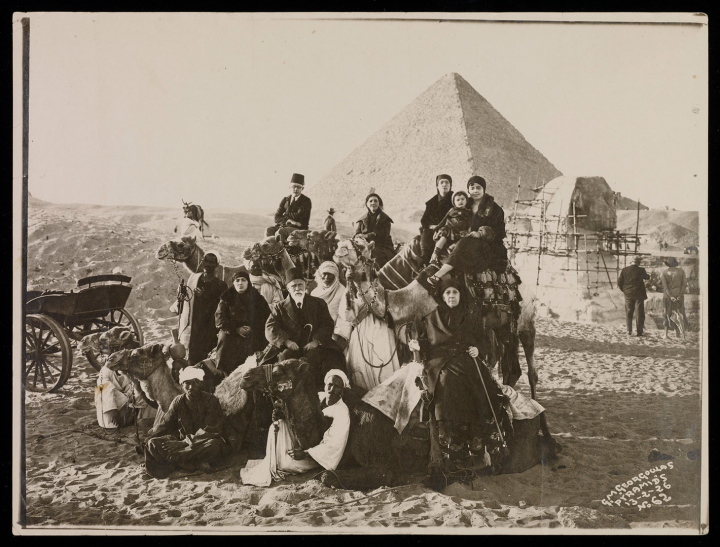

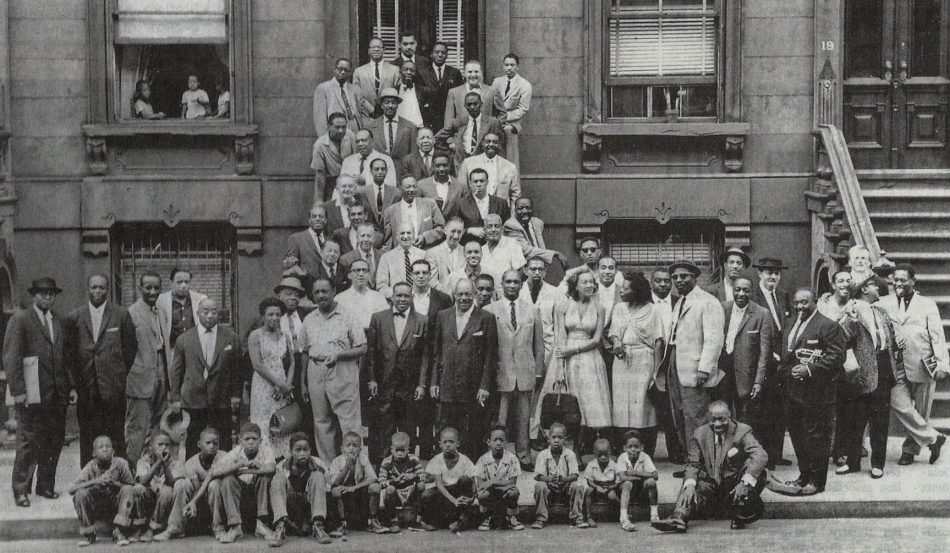

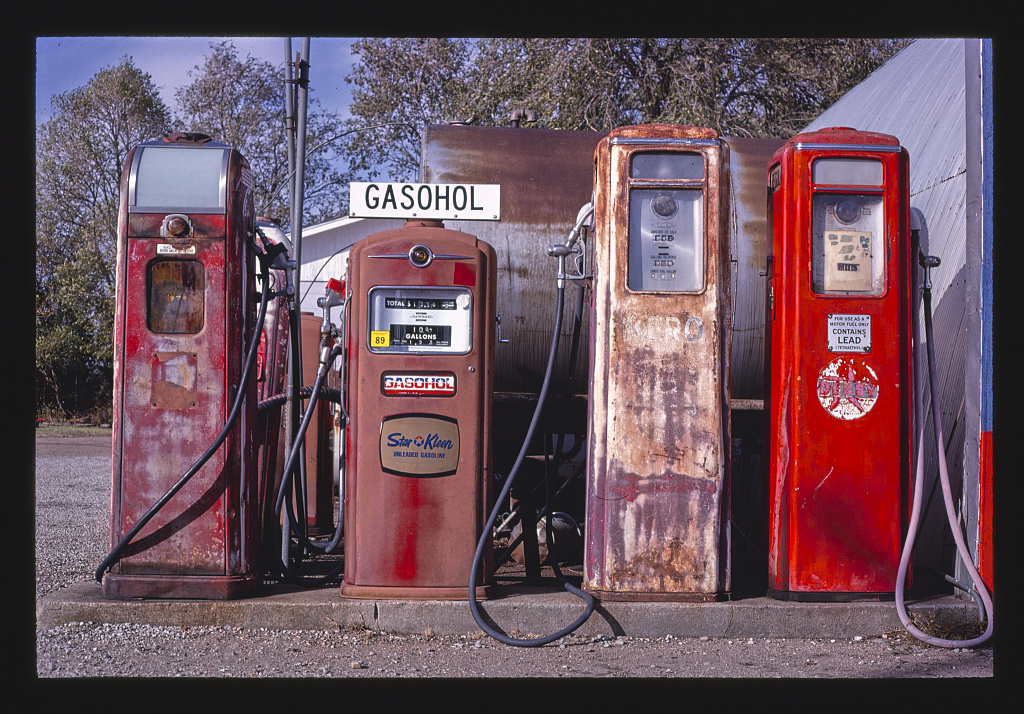

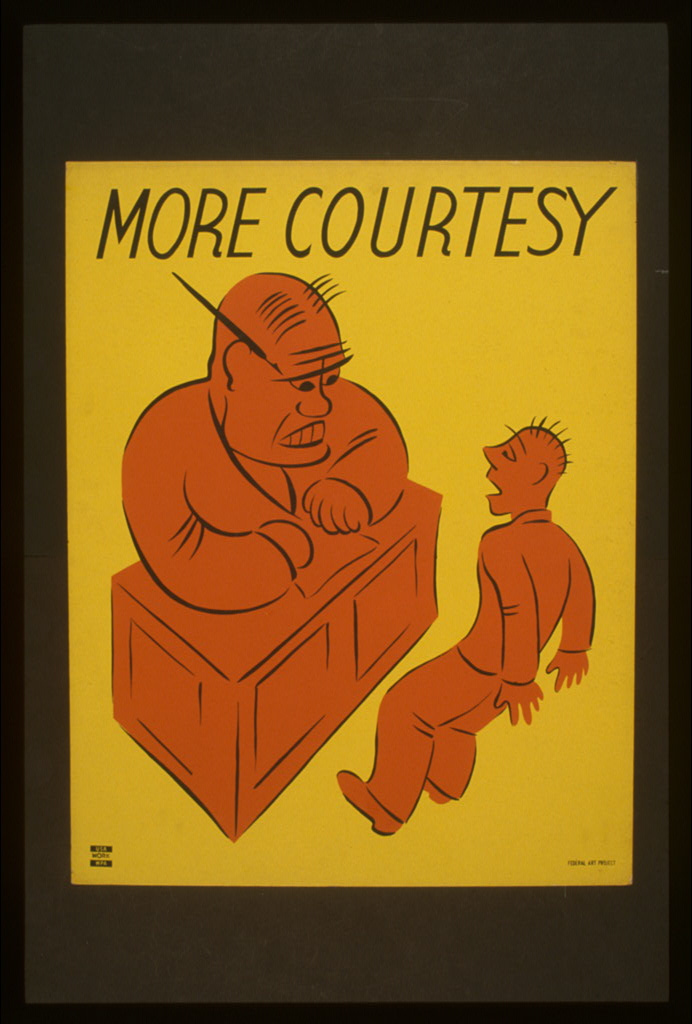

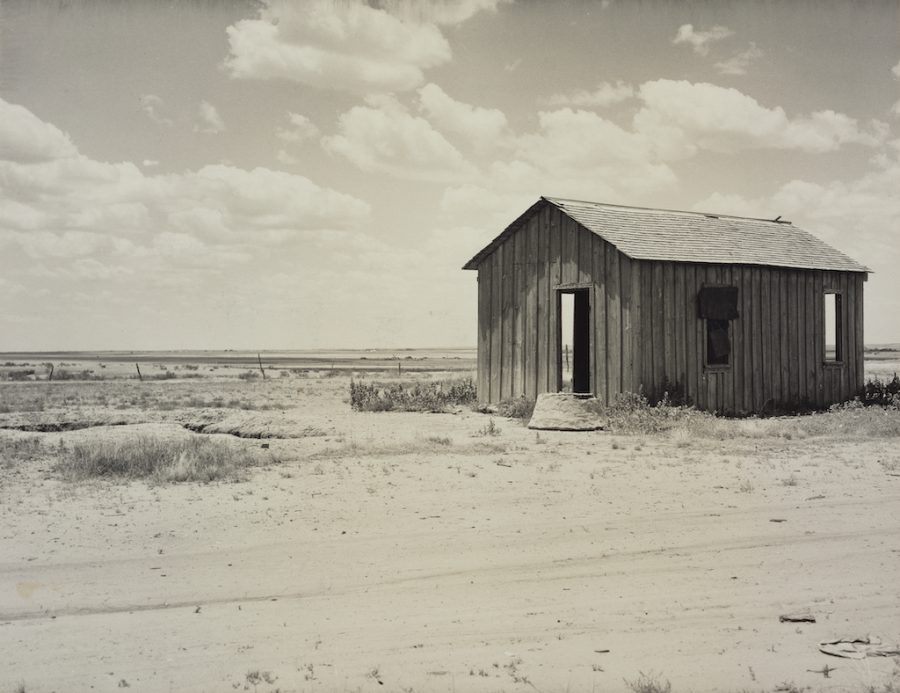

But the bulk of the digital collection consists of photographs, with 112,261 images and counting in the archive. The Getty has “assembled the finest and most comprehensive corpus of photographs on the West Coast” in its photography collection (not to be confused with Getty’s son’s media empire), with “substantial holdings by some of the most significant masters of the 20th century.” The collection is also “particularly rich in works dating from the time of photography’s invention” and its development in the mid-19th century.

Download and study Dorothea Lange’s desolate Abandoned Dust Bowl Home. Or journey back to the early days of the medium, when gentleman amateurs like Scottish nobleman Ronald Ruthven Leslie-Melville took up photography as an avid pursuit, and documented the landscapes, architecture, and personages of their age. (See Ruthven-Melville’s 1860’s photograph Roehampton below.)

Like all digital collections, the Getty’s cannot replicate the experience of seeing physical works of art in person, but it does magnanimously expand access to thousands of images usually hidden from the public, as well as thousands of pieces currently on display in one of its many museums. Completely free, the online archive serves as an invaluable teaching and learning tool, a vast repository preserving international art history online.

Related Content:

1.8 Million Free Works of Art from World-Class Museums: A Meta List of Great Art Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness