All of us here in the 2010s have, at one time or another, been street photographers. But up until 1838, nobody had ever been a street photographer. In that year when camera phones were well beyond even the ken of science fiction, Louis Daguerre, the inventor of the daguerreotype process and one of the fathers of photography itself, took the first photo of a human being. In so doing he also became the first street photographer, capturing as his picture did not just a human being but the urban environment inhabited by that human being, in this case Paris’ Boulevard du Temple. Daguerre’s picture begins the historical journey through 181 years of street photography, one street photo per year all soundtracked with period-appropriate songs, in the video above.

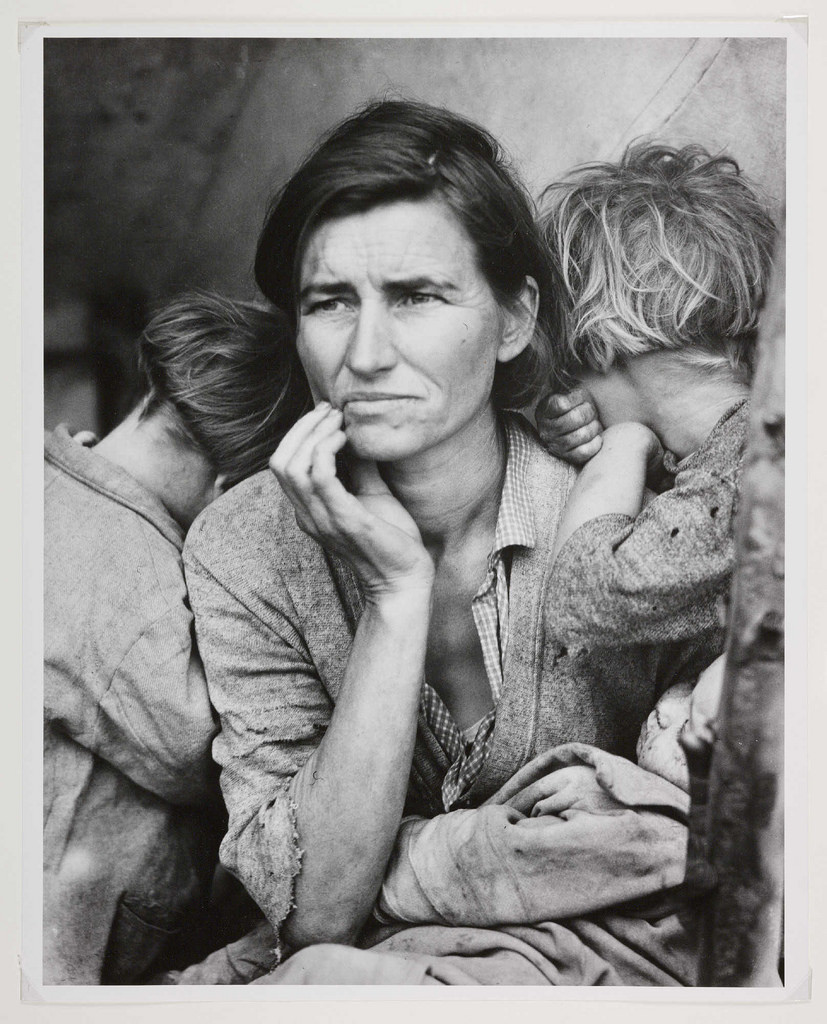

From the dawn of the practice, street photography (unlike smile-free early photographic portraiture) has shown life as it’s actually lived. Like the lone Parisian who happened to be standing still long enough for Daguerre’s camera to capture, the people populating these images go about their business with no concern for, or even awareness of, being photographed.

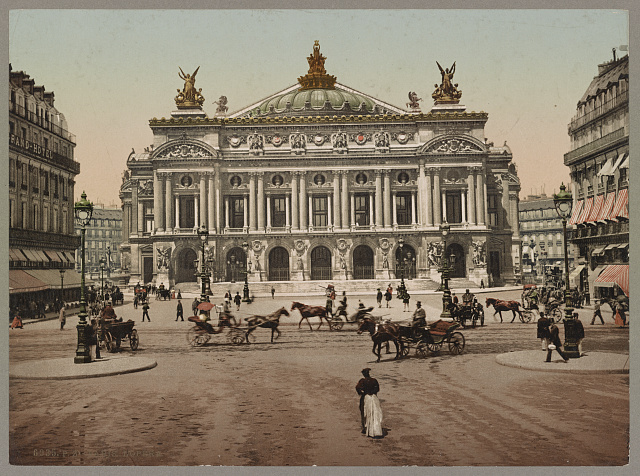

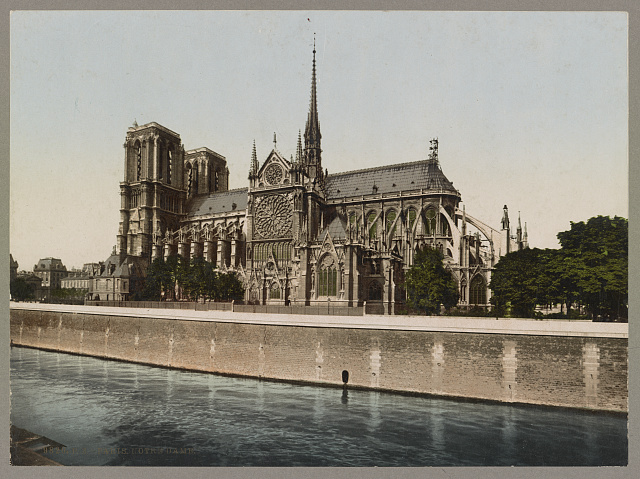

The earliest street photographs come mostly from Europe — London’s Trafalgar Square, Copenhagen’s former Ulfeldts Plads (now Gråbrødretorv), Rome’s Via di Ripetta — but as photography spread, so spread street photography. Rapidly industrializing cities in America and elsewhere in the former British Empire soon get in on the action, and a few decades later scenes from the cities of Asia, Africa, and the Middle East begin to appear.

Each of these 181 street photographs was taken for a reason, though most of those reasons are now unknown to us. But some pictures make it obvious, especially in the case of the startlingly common subgenre of post-disaster street photography: we see the aftermath of an 1858 brewery fire in Montreal, an 1866 explosion in Sydney, an 1874 flood in Pittsburgh, a 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, and a 1920 bombing in New York. Each of these pictures tells a story of a moment in the life of a particular city, but together they tell the story of the city itself, as it has over the past two centuries grown outward, upward, and in every other way necessary to accommodate growing populations; transportation technologies like bicycles, streetcars, automobiles; spaces like squares, cinemas, and cafés; and above all, the ever-diversifying forms of human life lived within them.

Related Content:

Humans of New York: Street Photography as a Celebration of Life

19-Year-Old Student Uses Early Spy Camera to Take Candid Street Photos (Circa 1895)

Vivian Maier, Street Photographer, Discovered

See the First Photograph of a Human Being: A Photo Taken by Louis Daguerre (1838)

The History of Photography in Five Animated Minutes: From Camera Obscura to Camera Phone

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.