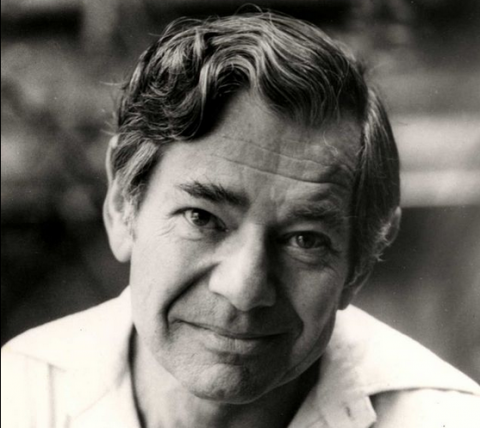

For better or worse, Alain de Botton is the face of pop philosophy. He has advocated “religion for atheists” in a book of the same name (to the deep consternation of some atheists and the eloquent interest of others); he has distilled selected philosophical nuggets into self-help in his The Consolations of Philosophy; and most recently, he’s tackled a subject close to everybody’s heart (to put it charitably) in How to Think More About Sex. As a corollary to his intellectual interests in human betterment, de Botton also oversees The School of Life, a “cultural enterprise offering good ideas for everyday life” with a base in Central London and a colorful online presence. Many critics disdain de Botton’s shotgun approach to philosophy, but it gets people reading (not just his own books), and gets them talking, rather than just shouting at each other.

In addition to his publishing, de Botton is an accomplished and engaging speaker. Although himself a committed secularist, in his TED talks, he has posed some formidable challenges to the smug certainties of liberal secularism and the often brutal certainties of libertarian meritocracy. Apropos of the latter, in the talk above, de Botton takes on what he calls “job snobbery,” the dominant form of snobbery today, he says, and a global phenomenon. Certainly, we can all remember any number of times when the question “What do you do?” has either made us exhale with pride or feel like we might shrivel up and blow away. De Botton takes this common experience and draws from it some interesting inferences: for example, against the idea that we (one assumes he means Westerners) live in a materialistic society, de Botton posits that we primarily use material goods and career status not as ends in themselves but as the means to receive emotional rewards from those who choose how much love or respect to “spend” on us based on where we land in any social hierarchy.

Accordingly, de Botton asks us to see someone in a Ferrari not as greedy but as “incredibly vulnerable and in need of love” (he does not address other possible compensations of middle-aged men in overly-expensive cars). For de Botton, modern society turns the whole world into a school, where equals compete with each other relentlessly. But the problem with the analogy is that in the wider world, the admirable spirit of equality runs up against the realities of increasingly entrenched inequities. Our inability to see this is nurturned, de Botton points out, by an industry that sells us all the fiction that, with just enough know-how and gumption, anyone can become the next Mark Zuckerberg or Steve Jobs. But if this were true, of course, there would be hundreds of thousands of Zuckerbergs and Jobs.

For de Botton, when we believe that those who make it to the top do so only on merit, we also, in a callous way, believe those at the bottom deserve their place and should stay there—a belief that takes no account of the accidents of birth and the enormity of factors outside anyone’s control. This shift in thinking, he says—especially in the United States—gets reflected in a shift in language. Where in former times someone in tough circumstances might be called “unfortunate” or “down on their luck,” they are now more likely to be called “a loser,” a social condition that exacerbates feelings of personal failure and increases the numbers of suicides. The rest of de Botton’s richly observed talk lays out his philosophical and psychological alternatives to the irrational reasoning that makes everyone responsible for everything that happens to them. As a consequence of softening the harsh binary logic of success/failure, de Botton concludes, we can find greater meaning and happiness in the work we choose to do—because we love it, not because it buys us love.

Related Content:

Alain De Botton Turns His Philosophical Mind To Developing “Better Porn”

Alain de Botton’s Quest for The Perfect Home and Architectural Happiness

Socrates on TV, Courtesy of Alain de Botton (2000)

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness