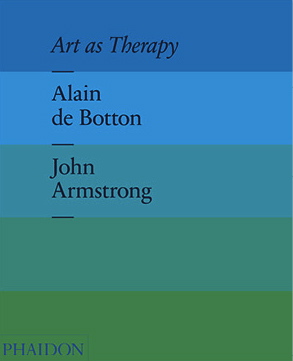

Alain de Botton, pop philosopher, has come out with a new book. Like his others, it’s full of sweeping ideas about an entire mode of human existence. He’s written on religion, sex, success, and happiness, and now he takes on art in Art as Therapy, co-written with art historian and author John Armstrong. Like all of de Botton’s ventures, the new book is sure to polarize. Many people find his work powerful and immediate, many see it as blithe intellectual tourism. To the latter critics, one might reply that de Botton’s approach is somewhat like that of other non-professional philosophers ancient and modern, from Plato to Schopenhauer, who addressed any and every area of life. And yet de Botton is a professional of another kind—he is a professional author, speaker, and self-help guru, and unlike his predecessors, he expressly sells a product. There’s no inherent reason why this should render his philosophy suspect. Yet, to use a favorite descriptor of his, some may find his media savviness vulgar, as Socrates found the so-called “sophists” of his day (a term of abuse that may be generally undeserved then and now).

In the video above—one of de Botton’s “Sunday Sermons” for his School of Life, an organization that more and more resembles his vision of a “religion for atheists”—de Botton lays out the book’s argument in a pretty unconventional way. The intro looks exactly like an evangelical church service, scored by a Robbie Williams song, which de Botton uses as his first example of “art.” It’s a tongue-in-cheek demonstration of de Botton’s claim that “art is our new religion… culture is something that is imminently suited to filling [religion’s] shoes.” Whether all of this large talk, pseudo-religiosity, and Robbie Williams music inspires, bores, or disturbs you is a personal matter, I suppose, but it does prepare one for something very different from a philosophical lecture in any case. This is, in fact, a sermon, replete with literary and theoretical references, tailored to offer answers to Life’s Big Questions.

De Botton first identifies the problem. While the secular gatekeepers of culture pretend to believe in the mollifying spiritual effects of art, “in fact,” he says, “the idea is dead.” Museums are moribund because, for example, they don’t directly address individual’s fear of death. Presumably, his “art as therapy” approach does. The book’s website contains snippets divided into broad categories like “Politics,” “Work,” “Love,” “Anxiety,” “Self,” and “Free Time.” In his sermon, de Botton doesn’t seem to evince any recognition of the field of art therapy, which has been chugging along since the early 20th century, but as he tells Joshua Rothman in an interview for The New Yorker he means the word therapy—“a big, simple, vulgar word”—broadly. Sounding for all like an Anglican theologian, de Botton says of an annunciation altarpiece by Fra Fillippo Lippi:

De Botton first identifies the problem. While the secular gatekeepers of culture pretend to believe in the mollifying spiritual effects of art, “in fact,” he says, “the idea is dead.” Museums are moribund because, for example, they don’t directly address individual’s fear of death. Presumably, his “art as therapy” approach does. The book’s website contains snippets divided into broad categories like “Politics,” “Work,” “Love,” “Anxiety,” “Self,” and “Free Time.” In his sermon, de Botton doesn’t seem to evince any recognition of the field of art therapy, which has been chugging along since the early 20th century, but as he tells Joshua Rothman in an interview for The New Yorker he means the word therapy—“a big, simple, vulgar word”—broadly. Sounding for all like an Anglican theologian, de Botton says of an annunciation altarpiece by Fra Fillippo Lippi:

There’s a sudden tenderness here, which is so far removed from the harshness outside. If I were to put a caption here, it might say: ‘Our world, for all its technological sophistication, is lacking in certain qualities. But this painting is a visitor from another world, where those qualities—tenderness, reverence, and modesty—are very highly valued. Take it as an argument against Fox News and the New York Post. Use it to find the still places in yourself.’

The notion of this piece of art as “an argument” on the same conceptual plane as corporate mass media seems to contradict de Botton’s premise that it’s “from another world.” This cheek-by-jowl referencing of the sacred and profane, high and low, offends the sensibilities of several philosophical thinkers, and may have offended Fra Fillippo Lippi. But perhaps it’s too easy to be cynical about de Botton’s populist approach. If all of his evangelism seems like nothing more than elaborate publicity for his books, he’s certainly made things difficult for himself by founding a school. Whether you find his ideas compelling or not, he proves himself a passionate, if not particularly modest, thinker attempting to grapple with the problems of middle-class Western malaise and existential angst.

Related Content:

Alain De Botton Turns His Philosophical Mind To Developing “Better Porn”

A Guide to Happiness: Alain de Botton Shows How Six Great Philosophers Can Change Your Life

Alain de Botton Proposes a Kinder, Gentler Philosophy of Success

Download 100 Free Online Philosophy Courses and Start Living the Examined Life

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness