Certainly three of the most radical thinkers of the last 150 years, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Sartre were also three of the most controversial, and at times politically toxic, for their perceived links to totalitarian regimes. In Nietzsche’s case, the connection to Nazism was wholly spurious, concocted after his death by his anti-Semitic sister. Nevertheless, Nietzsche’s philosophy is far from sympathetic to equality, his politics, such as they are, highly undemocratic. The case of Heidegger is much more disturbing—a member of the Nazi party, the author of Being and Time notoriously held fascist views, made all the more clear by the recent publication of his infamous “black notebooks.” And Sartre, author of Being and Nothingness, has long been accused of supporting Stalinism—a charge that may be oversimplified, but is not without some merit.

Despite these troubling associations, all three philosophers are often held up as representatives—along with Søren Kierkegaard and Albert Camus—of Existentialism, broadly a philosophy of freedom against oppressive religious and political systems that seek to define and order human life according to predetermined values. Whether all three thinkers deserve the label (Heidegger, like Camus, flatly rejected it) is a matter of some dispute, and yet, the BBC documentary series Human, All Too Human, named for Nietzsche’s 1878 collection of aphorisms, loosely uses the term to tie them together, acknowledging that it had yet to be coined in Nietzsche’s time.

The first episode, at the top, introduces the great 19th century German atheist by way of interviews with Nietzsche scholars and biographers. Episode two covers Heidegger, with frank discussions of his Nazi party affiliation and its implications for his thought.

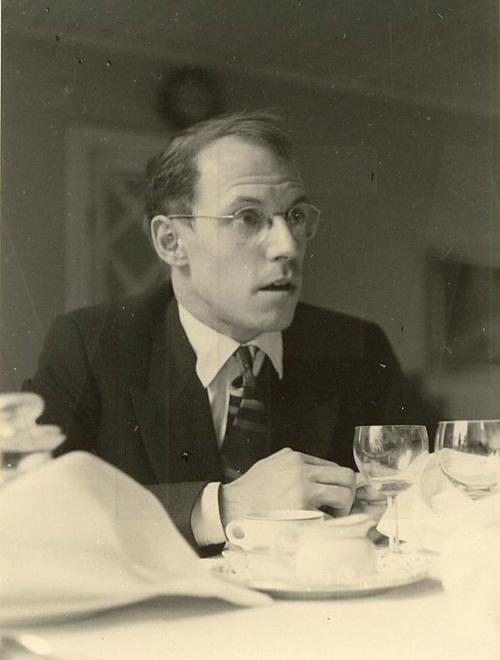

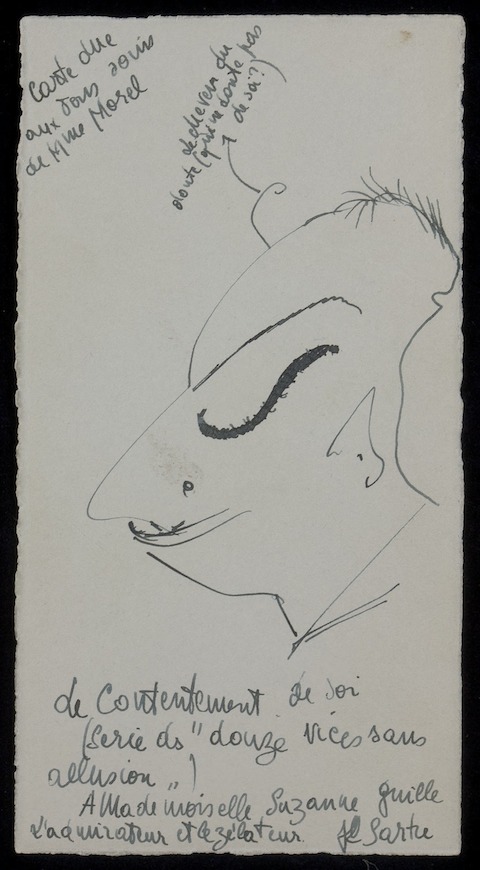

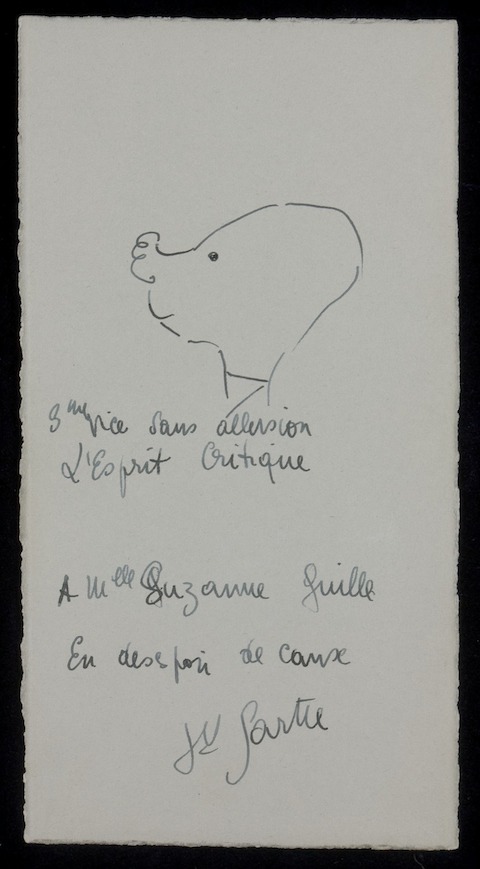

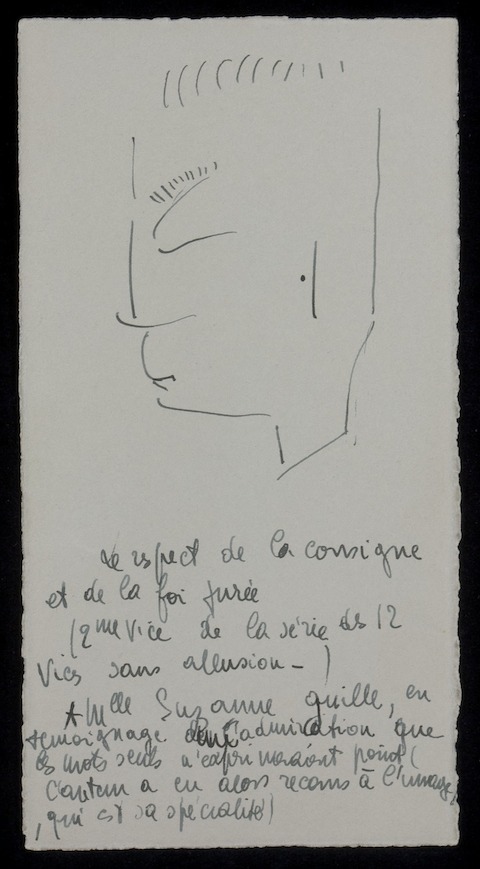

The third episode focuses on Sartre, the only thinker of the three to call himself an existentialist. Both Sartre and his partner Simone de Beauvoir wrote on the subject, defending the philosophical outlook in essays and interviews.

In one of Sartre’s most famous defenses, “Existentialism and Human Emotion,” he emphatically defines his philosophical stance as anti-essentialist and atheistic—unlike the Christian Kierkegaard before him.

Atheistic existentialism, which I represent, is more coherent. It states that if God does not exist, there is at least one being in whom existence precedes essence, a being who exists before he can be defined by any concept, and that this being is man, or, as Heidegger says, human reality. What is meant here by saying that existence precedes essence? It means that, first of all, man exists, turns up, appears on the scene, and, only afterwards, defines himself. If man, as the existentialist conceives him, is indefinable, it is because at first he is nothing. […] Thus, there is no human nature, since there is no God to conceive it. Not only is man what he conceives himself to be, but he is also only what he wills himself to be after this thrust toward existence.

Existentialism has become a wide net, used to capture similarities in the work of otherwise widely divergent thinkers. However, the use of the term historically belongs to the 1940s and 50s, to a movement as much literary as philosophical, and Sartre was its greatest champion and, some would say, the only true Existentialist philosopher. Nevertheless, the label captures something of the daring and the danger of radical philosophy that redefines, or outright rejects, traditional norms. For all their flaws and contradictions, all three of the thinkers profiled above made significant contributions to our understanding of what it means to be human—and to be an individual—in an increasingly mechanized, homogenized, and dehumanizing civilization.

Related Content:

Walter Kaufmann’s Classic Lectures on Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Sartre (1960)

Martin Heidegger Talks About Language, Being, Marx & Religion in Vintage 1960s Interviews

Philosophy’s Power Couple, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Featured in 1967 TV Interview

100 Free Philosophy Courses Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness