Once upon a time, questions about the use-value of art were the height of philistinism. “All art is quite useless,” wrote the aesthete Oscar Wilde, presaging the attitudes of modernists to come. Explaining this statement in a letter to a perplexed fan, Wilde opined that art “is not meant to instruct, or to influence action in any way.” But if you ask Alain de Botton, founder of “cultural enterprise” The School of Life, art—or literature specifically—does indeed have a practical purpose. Four to be precise.

In a pitch that might appeal to Dale Carnegie, de Botton argues that literature: 1) Saves you time, 2) Makes you nicer, 3) Cures loneliness, and 4) Prepares you for failure. The format of his video above—“What is Literature For?”—may be formulaic, but the argument may not be so contrary to modernist dicta after all. Indeed, as William Carlos Williams famously wrote, “men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found” in poetry. How many people perish slowly over wasted time, meanness, loneliness, and broken dreams?

Like de Botton’s short video introductions to philosophers, which we featured in a previous post, “What is Literature For?” comes to us with Monty Python-like animation and pithy narration that makes quick work of a lot of complex ideas. Whether you find this inspiring or insipid will depend largely on how you view de Botton’s broad-brush, populist approach to the humanities in general. In any case, it’s true that people crave, and deserve, more accessible introductions to weighty subjects like literature and philosophy, subjects that—as de Botton says above in “What is Philosophy For?”—can seem “weird, irrelevant, boring.…”

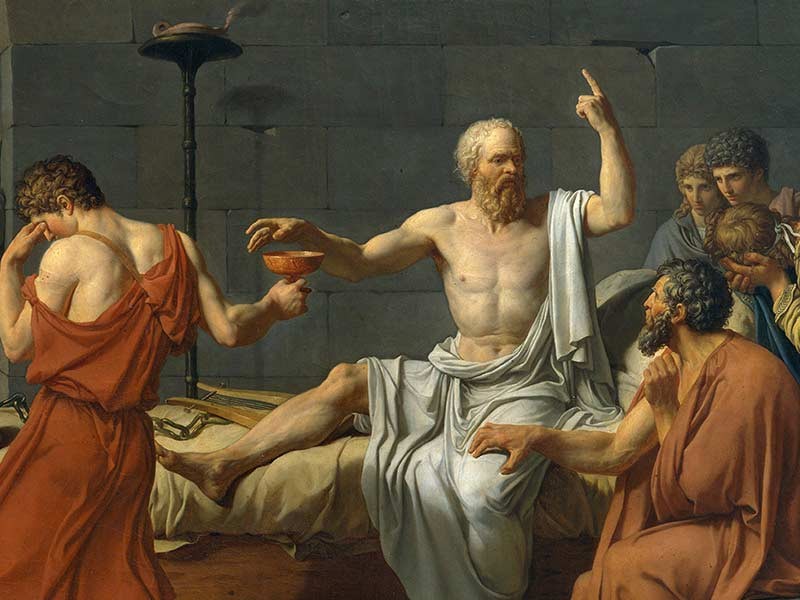

Here, contra Ludwig Wittgenstein’s claims that all philosophy is nothing more than confusion about language, de Botton expounds a very classical idea of the discipline: “Philosophers are people devoted to wisdom,” he says. And what is wisdom for? Its application, unsurprisingly, is also eminently practical. “Being wise,” we’re told, “means attempting to live and die well.” As someone once indoctrinated into the Byzantine cult of academic humanities, I have to say this definition seems to me especially reductive, but it does accord perfectly with The School of Life’s promise of “a variety of programmes and services concerned with how to live wisely and well.”

Lastly, we have de Botton’s explanation above, “What Is History For?” Most people, he claims, find the subject “boring.” Given the enormous popularity of historical drama, documentary film, novels, and popular non-fiction, I’m not sure I follow him here. The problem, it seems, is not so much that we don’t like history, but that we can never reach consensus on what exactly happened and what those happenings mean. This kind of uncertainty tends to make people very uncomfortable.

Unbothered by this problem, de Botton presses on, arguing that history, at its best, provides us with “solutions to the problems of the present.” It does so, he claims, by correcting our “bias toward the present.” He cites the obsessive jackhammering of 24-hour news, which shouts at us from multiple screens at all times. I have to admit, he’s got a point. Without a sense of history, it’s easy to become completely overwhelmed by the incessant chatter of the now. Perhaps more controversially, de Botton goes on to say that history is full of “good ideas.” Watch the video above and see if you find his examples persuasive.

All three of de Botton’s videos are brisk, upbeat, and very optimistic about our capacity to make good use of the humanities to better ourselves. Perhaps some of the more skeptical among us won’t be easily won over by his arguments, but they’re certainly worthy of debate and offer some very positive ways to approach the liberal arts. If you are persuaded, then dive into our collections of free literature, history and philosophy courses highlighted in the section below.

Related Content:

78 Free Online History Courses: From Ancient Greece to The Modern World

55 Free Online Literature Courses: From Dante and Milton to Kerouac and Tolkien

Download 100 Free Online Philosophy Courses & Start Living the Examined Life

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness