Punk rock and its accoutrements—including the handmade, Xeroxed ‘zine—pass into history, replaced by Taylor Swift and Snapchat, or whatever. But as a piece of history, the ‘zine will always stand as a marker of a particular era, of the 80s/early 90s explosion of critical consciousness fostered by young kids reading Nietzsche, Foucault, and Camus, then forming their own bands, labels, and networks. Crucial to the period is the emergence of Riot Grrrl bands like Bikini Kill and their assault on oppressive gender politics, in punk rock and everywhere else. And crucial to many such punks’ understanding of gender was the work of critical theorist Judith Butler.

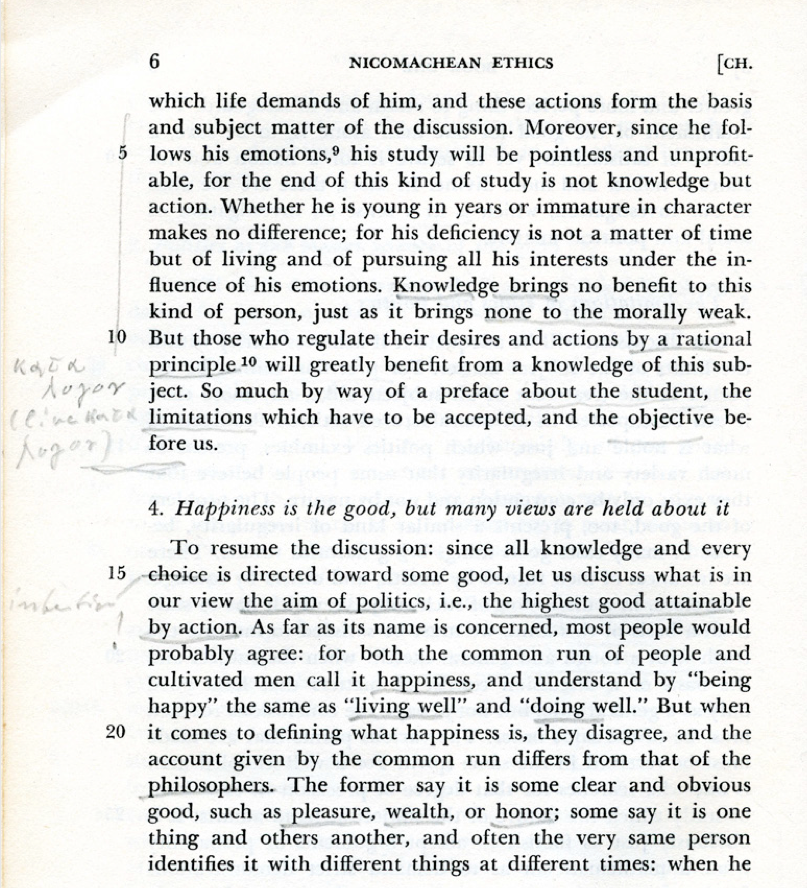

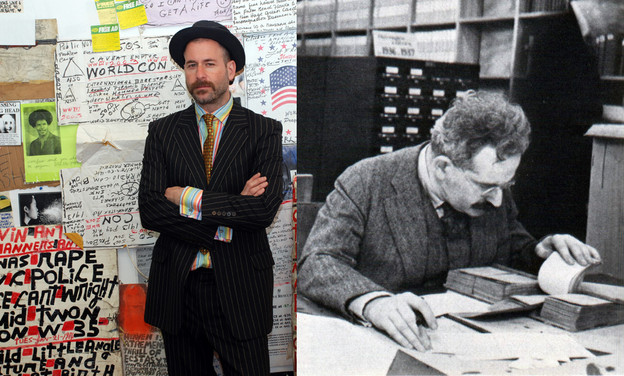

“Riot Grrrl didn’t herald the beginnings of third wave feminism,” writes Sophia Satchell Baeza in Canvas, “we’ll give that to the emergence of post-structuralist Queer theory, and the work of Judith Butler—but it did help define it aesthetically as much as formally for a new generation of indignant feminists.” An essential part of that aesthetic—the ‘zine—spread the tenets of Riot Grrrl anger, determination, and irony to cities far and wide. And, in 1993, a group of intellectual scenesters created the ultimate punk homage to Butler’s undeniable influence: Judy!, an honest-to-goodness Judith Butler fanzine, complete with murky, mimeographed photo spreads and serial killer typescript. (See the cover at the top, with photo of Judy Garland.) “Let’s talk about that real glamour gal of theory, Judy Butler,” begins one free-form introductory essay.

She’s especially good to see live, if you can. Her performances are rife with witty repartee about her mom or whatever and the three times I’ve seen her, she’s been sporting little tailored black jackets. She’s a bit Gap but she’s still a fox.

This cavalier hipster tone hides the voice of a likely grad student, who mentions M.L.A. (the Modern Language Association’s conference), and other post-structuralist theorists like Gayatri Spivak, Eve Sedgwick, and Julia Kristeva. There are footnotes and references to Butler’s classic Gender Trouble amidst much more irreverent, catty rhetoric like “Judy is the number one dominator, and the only thing you or I can do is submit gladly.” It’s great fun, if that’s what you’re into—and if you get the combo of ‘zine aesthetic and academic feminist theory. There’s even a quiz to test your knowledge of the latter’s high priestess professors and inscrutable argot: “are you a theory-fetishizing biscuithead?”

As much as it knowingly pokes fun at itself, in both form and content the artifact represents a perfect hybridization of streetwise mid-nineties punk rock and challenging mid-nineties high feminist theory. Central to the latter, Judith Butler challenges cultural norms in ways that very much inform our popular understanding of gender and sexuality today. And ‘zine culture, though it may appear mostly in museums and retrospectives these days, lives on in spirit in the work of hip, cultural mavens like Rookie’s Tavi Gevinson. Above, see Butler discuss her theory of gender performativity. And Read the entire issue of Judy!, the fanzine, here.

via Progressive Geographies

44 Essential Movies for the Student of Philosophy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.