Image via Wikimedia Commons

Is it possible to fully separate a word’s sound from its meaning—to value words solely for their music? Some poets come close: Wallace Stevens, Sylvia Plath, John Ashbery. Rare phonetic metaphysicians. Surely we all do this when we hear words in a language we do not know. When I first encountered the Spanish word entonces, I thought it was the most beautiful three syllables I’d ever heard.

I still thought so, despite some disappointment, when I learned it was a commonplace adverb meaning “then,” not the rarified name of some magical being. My reverence for entonces will not impress a native Spanish speaker. Since I do not think in Spanish and struggle to find the right words when I speak it—always translating—the sound and sense of the language run on two different tracks in my mind.

An example from my native tongue: the word obdurate, which I adore, became an instant favorite for its sound the first time I said it aloud, before I’d ever used it in a sentence or parsed its meaning. It’s not a common English word, however, and maybe that makes it special. A word like always, which has a pretty sound, rarely strikes me as musical or interesting, though non-English speakers may find it so.

Every writer has favorite words. Some of those words are ordinary, some of them not so much. David Foster Wallace’s lists of favorite words consist of obscurities and archaisms unlikely to ever feature in the average conversation. “James Joyce thought cuspidor the most beautiful word in the English language,” writes the blog Futility Closet,” Arnold Bennet chose pavement. J.R.R. Tolkien felt the phrase cellar door had an especially beautiful sound.”

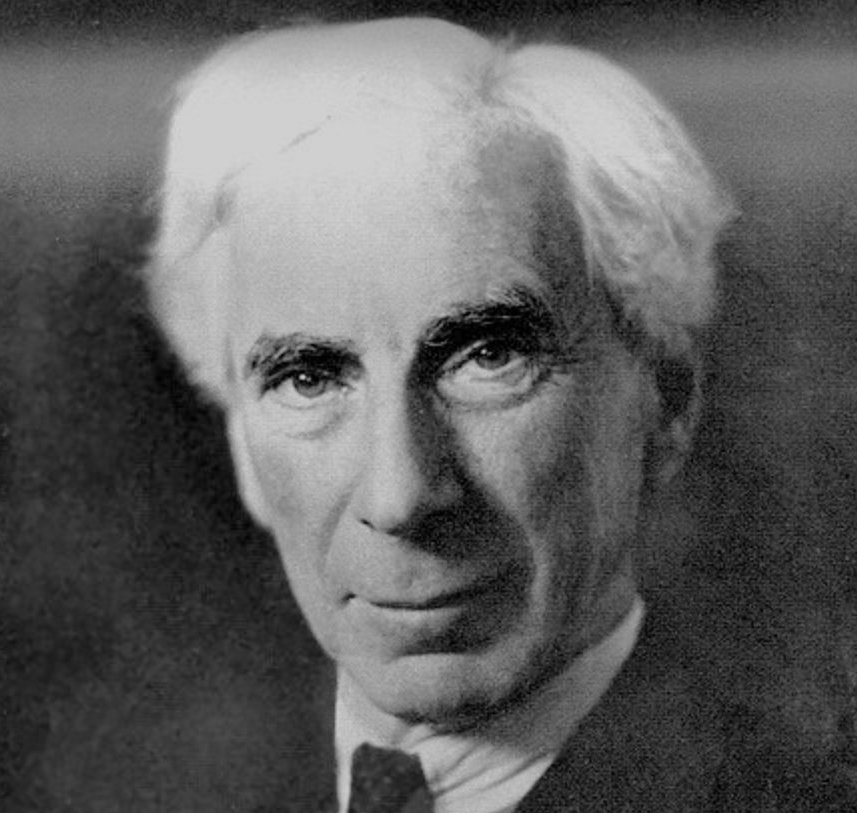

Who’s to say how much these authors could separate sound from sense? Futility Closet illustrates the problem with a humorous anecdote about Max Beerbohm, and brings us the list below of philosopher Bertrand Russell’s 20 favorite words, offered in response to a reader’s question in 1958. Though Russell himself had a fascinating theory about how we make words mean things, he supposedly made this list without regard for these words’ meanings.

- wind

- heath

- golden

- begrime

- pilgrim

- quagmire

- diapason

- alabaster

- chrysoprase

- astrolabe

- apocalyptic

- ineluctable

- terraqueous

- inspissated

- incarnadine

- sublunary

- chorasmean

- alembic

- fulminate

- ecstasy

So, what about you, reader? What are some of your favorite words in English—or whatever your native language happens to be? And do you, can you, choose them for their sound alone? Please let us know in the comments below.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness