Since the bold arrival of his book Of Grammatology in 1967, French philosopher Jacques Derrida has been understood—or misunderstood—as many things: a radical relativist who ”rejects all of metaphysical history,” a fashionable intellectual playing language games, a brilliant phenomenologist of language…. One association he vehemently rejected was with the kind of ironic, laissez faire postmodernism represented by Seinfeld. But when it came to clarifying his work for puzzled readers and onlookers, Derrida could seem as willfully, frustratingly evasive in person as he was on the page. His work, writes Williams College professor Mark C. Taylor, can “seem hopelessly obscure… to people addicted to sound bites and overnight polls.”

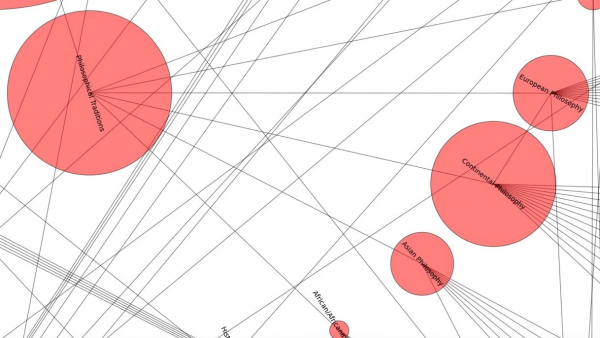

Most people familiar with some of Derrida’s work know a few key terms of his thought: différance, trace, aporia, pharmakon. Those who’ve only heard the name probably know only one: Deconstruction, a “way of doing philosophy,” says Alain de Botton in his video introduction to Derrida above, that “fundamentally altered our understanding of many academic fields, especially literary studies.” But what exactly is “Deconstruction”? Rather than a method, Derrida himself described it as a process already occurring within a written work, one we can observe when we “do not assume that what is conditioned by history, institutions, or society is natural.”

Derrida’s meditations on the inability of language to contain or communicate natural or metaphysical truth developed in unique life circumstances. Born into a Jewish family in French colonial Algeria in 1930, the philosopher grew up very conscious of “having been in an inferior position at the nexus of three different religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, all of which claimed to speak the truth,” says de Botton. Upon arriving in Paris to study in 1949, Derrida found himself even further on the social margins. “Though Derrida was not an autobiographical writer, it’s hard not to read his work as a response to bigotry and exclusion.”

The claim that the philosopher—whose name has almost become synonymous with post-modernism, for good or ill—was not an autobiographical writer may seem strange to some. One of his most-read books in college courses, Monolingualism of the Other, proceeds from an investigation into his fraught relationship with the French language because of his upbringing as a religious minority in a European colony. Later, Derrida delivered a ten-hour address to a conference called The Autobiographical Animal, published posthumously (and excerpted here).

Nonetheless, Derrida would not have made much of his place as the author, this being only a rhetorical occasion for analysis. Derrida, writes Nazenin Ruso at Philosophy Now, argued that “once the text is written, the author’s input loses its significance.” The person of the author—his or her physical presence, biographical experiences, emotions, desires, and intentions—becomes irretrievable for readers, one of many absences in the text that we mistake for presence.

It’s hard to see, then, how we can speak of what Derrida’s “hope” was for his readers’ self-improvement, as de Botton says in his video introduction. This being the School of Life, we are treated to a rather utilitarian reading of the philosopher, one he would perhaps reject. But Derrida bristled at the idea that language could suffice to tell us how and who to be in the world. His suspicion of logocentrism, “an over-hasty, naïve devotion to reason, logic, and clear definition,” says de Botton, means he felt that “many of the most important things we feel can never be expressed in words.” To hear Derrida talk about the problem of privileging language over other means of expression with an artist who uniquely agreed with his position, read his interview with jazz great Ornette Coleman.

Related Content:

140 Free Online Philosophy Courses

Jacques Derrida on Seinfeld: “Deconstruction Doesn’t Produce Any Sitcom”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness